|

|

|

In the last decade, new experimental approaches addressing blood clotting and thrombosis in vivo have attracted a lot of attention. Several animal models utilizing intravital microscopy and different techniques of inducing vascular injury have been described.1, 2, 3 The main technical principle of such in vivo studies of thrombosis is exposure of blood vessels (while blood is still circulating) and causing injury to the vascular wall by means of a chemical agent or laser, leading to blood coagulation.1, 2, 3 The obvious advantage of animal models is that thrombus formation is observed in its natural environment in the absence of artificial anticoagulants, which are essential for in vitro methods.1, 2, 3 There are a few drawbacks with current animal model methodologies. For example, observation of blood clotting can be performed only at sites where blood vessels are clearly visualized, and therefore skin thickness becomes a limiting factor. Usually, a surgical procedure is needed to expose optically transparent tissue with distinct blood circulation networks (e.g., mesenterium). Thrombosis may also be monitored using fluorescent microscopy, which requires administration of fluorescent markers to label various blood components or clotting factors.2, 3 The goal of the present study was to develop an optimized experimental approach for noninvasive visualization of blood clotting in vivo. Specifically, we aimed to establish an experimental protocol that will allow one to visualize fine changes in red blood cell (RBC) motion at high spatial and temporal resolution, deep inside tissue. This protocol should be easy to use, allowing for potential application in humans. There are a number of optical techniques that potentially could be useful for determination and visualization of RBC motion in vivo, such as: diffusing wave spectroscopy (DWS), diffuse laser Doppler velocimetry (DLDV), Doppler optical coherence tomography (DOCT), and especially laser speckle imaging. For example, various modifications of dynamic light scattering (DLS) such as laser Doppler and laser speckle techniques are already in use both in vitro and in vivo settings (e.g., deep tissue imaging and blood flow determination,4 or determination of blood plasma coagulation in vitro 5). A modified DLS imaging technique (based on full-field analysis of laser speckle pattern) was the optimal method for our study. In fact, this method was simple and capable of imaging the full field of RBC motion or blood flow inside small blood vessels without scanning. Another point was that it provided a much higher spatial and temporal resolution than other laser Doppler perfusion imaging methods.4 The main novelty of the approach presented here is that experiments were performed on previously occluded blood vessels, and detection was carried out by a modified DLS technique as described later. The usefulness of temporary mechanical occlusion for the in vivo monitoring of blood clotting was based on the following reasons.

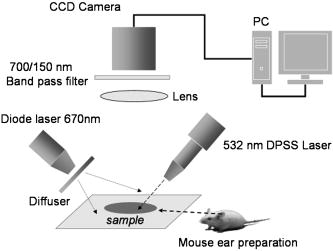

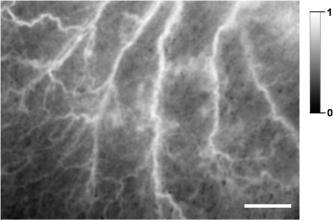

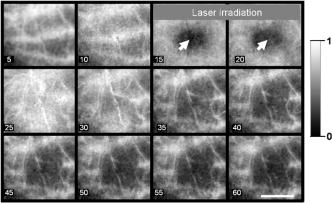

This work was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Weizmann Institute of Science. CD1 nude mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine ( i.p.) for all experiments. Anesthetized animals were placed on the stage of a setup for intravital microscopy. Temporary blood flow interruption (occlusion) was achieved by using a mechanical occluder, which produces a gentle and local mechanical pressure on the area of large arteries within the mouse ear. The duration of occlusion did not exceed . In the first set of experiments, the mouse ear with occluded blood vessels was imaged via a microscope AxioImager (Zeiss, Germany) and by a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera Pixelfly (PCO, Germany). The exposure time of the CCD was . Images were acquired through easy-control software at 20 frames per second. We observed that mechanical occlusion of major blood vessels in the mouse ear never leads to a complete blood flow stasis in microvessels, as shown in Fig. 1 . Even after maximal occlusion, RBCs continued to move, and the character of this motion was not stochastic. The observed movements of a great majority of the RBCs were unidirectional and parallel to the vessel walls. Fig. 1Sequential microscopic images of RBC motion inside a single capillary. Major blood vessels were occluded prior to imaging. Single RBC is outlined (starting point is outlined by the dashed line). Scale bar . The image was taken using transmitted illumination. Image contrast was enhanced.  RBCs were moving for up to after animals were euthanatized. This phenomenon was observed in all experimental animals . Therefore, we hypothesized that the absence of RBC motion in an occluded vessel might be a sign of blood clotting in vivo, since polymerized fibrin can prevent even minimal movements of RBCs. To monitor the blood clotting process, as well as to solve the problem of light scattering by skin and tissue, we have used DLS from laser light for imaging the fine changes in RBC motion inside occluded vessels through the skin of the mouse ear. It is critical to note that in the second set of experiments, we used the same animal model and procedures for animal care as described before. A schematic diagram of the setup for this set of experiments is presented in Fig. 2 . The first (red) diode laser was coupled with a diffuser, which was adjusted to illuminate the area of a mouse ear. The illuminated area was imaged through a zoom stereo microscope SZX12 (Olympus, Japan) and by a CCD camera Pixelfly (PCO, Germany). A second (green) diode-pumped solid state (DPSS) laser module (Laser-Glow, Canada, , ) was used for the purpose of inducing micro-injury. The bandpass filter was placed between the lens and CCD camera to prevent camera saturation during the second (green) laser irradiation. The exposure time of the CCD was . Images were acquired through easy-control software at . Analysis of acquired image sequences was performed on ImageJ with a specifically designed software package for the analysis. DLS imaging of RBC motion in occluded microvessels was based on the temporal contrast of intensity fluctuations produced from laser speckles that reflected from mouse tissue. Briefly, the laser speckle is an interference pattern produced by the light reflected or scattered from different parts of an illuminated surface. When an area is illuminated by the first (red) laser light and is imaged onto a camera, a granular or speckle pattern is produced. If the scattered particles are moving, a time-varying speckle pattern is generated at each pixel in the image. The intensity variations of this pattern contain information about the speed of the scattered particles. We have utilized the temporal statistics of time integrated speckles to obtain a 2-D velocity map, which represents blood vessels under flow and no-flow conditions. The value of the laser temporal contrast at pixel was calculated based on the following formula: where is a standard deviation of the CCD intensity counts at pixel during frames. is the number of frames acquired , and is the mean value of CCD intensity counts at pixel over the frames.14, 15, 16Temporal mechanical occlusion of blood vessels in the observed area was applied, as described before, to ensure blood flow cessation. As shown in Fig. 3 , laser temporal speckle contrast is higher inside blood vessels. This is represented by the “white” pattern and indicates the presence of motion inside occluded blood vessels. The darker areas represent areas of low or negligible motions. Fig. 3Laser-based DLS imaging of a mouse ear after complete occlusion of major ear blood vessels. Intensity scale on the right is the value of laser speckle temporal contrast. Scale bar is . Large blood vessels appeared as white wires. White and fuzzy background corresponds with the signal produced by RBC movements in capillaries.  In addition, after occlusion, the beam of a second (green) DPSS laser was directed (at an angle of 45 degrees or less) onto the ear of an anesthetized mouse. The laser was focused to create a pinpoint injury on the mouse ear . The injury was induced with a short high intensity laser burst at the area, indicated by white arrows in frames 15 and (see Fig. 4 ). Herein the “white” pattern of blood vessels during DLS imaging of occluded blood vessels in the mouse ear can be explained by remaining RBC motion. Conversely, relative changes in the intensity of on clotting can be caused by elevation of blood/plasma viscosity as a result of blood clotting, as shown in Fig. 4. We observed a decrease of RBC motions in capillaries and larger vessels after laser irradiation, which corresponded with decreases of the intensity of . This occurred not only and exactly at the moment of irradiation (there is no significant decrease of inside the postirradiated area immediately after laser irradiation, as shown in Fig. 4, frames 25 and 30), but there is a decrease of after a lag period inside the postirradiated area, as shown in (Fig. 4, frames 35 to 60). This observation corresponds with the physiologic process of blood clot formation after injury, because the formation of fibrin clot requires time for enzymatic reactions to occur.1 Fig. 4DLS imaging of a mouse ear after complete occlusion of major ear blood vessels and laser irradiation. Scale bar is . Intensity scale on the right is the value of laser speckle temporal contrast. Blood vessels appeared as relatively narrow white vertical lines. White and fuzzy background corresponds with signal produced by RBC movements in capillaries. Numbers on the bottom left corner are seconds after start of recording. White arrow shows place of laser irradiation. The dark spot in the middle during laser irradiation is an optical effect produced by laser-induced autofluorescence. 5, 10: before laser irradiation. 15, 20: laser irradiation. 25 to 60: after laser irradiation.  In our experiments, two elements of Virchow’s triad were used to induce the process of clotting in vivo and to assess it optically. Both changes in the vessel wall, as well as in the pattern of blood flow, predispose the area to vascular thrombosis and blood clotting. Thus, we used DLS images generated by RBC motion inside occluded blood vessels as markers of the blood clotting process in vivo. In closing, DLS imaging based on temporal laser speckle contrast is applicable for noninvasive investigation of blood clotting in vivo during mechanical occlusion. A potential advantage of this method is avoidance of use of any fluorescent or artificial chemicals that would be unnecessary for in vivo coagulation monitoring in humans. The approach described allows for the detection of fine changes in RBC motion during occlusion in the vascular system through the skin, as shown in our experiments up to a depth of . It is quite possible, however, that further development of the system will allow one to achieve better resolution and greater depth of a detectable signal. This method requires further development, because our experiments were performed solely on a mouse ear model. Additional efforts should be made to test this noninvasive method on other animal models (murine and nonmurine), and ultimately on humans in a clinical setting. AcknowledgmentsWe especially want to thank Kirill Burd for his development of the software analysis package used in this study. ImageJ is being developed at the National Institutes of Health, USA, by Wayne Rasband. The occlusion of blood vessels and the subsequent noninvasive technology utilized to detect physical parameters of blood circulation is described in Elfi Tech Limited. provisional patent application number 60/788,074 and full patent application number 11/604,401. ReferencesB. Furie and

B. C. Furie,

“Thrombus formation in vivo,”

J. Clin. Invest., 115 3355

–3362

(2005). 0021-9738 Google Scholar

A. Celi,

G. Merrill-Skoloff,

P. Gross,

S. Falati,

D. S. Sim,

R. Flaumenhaft,

B. C. Furie, and

B. Furie,

“Thrombus formation: direct real-time observation and digital analysis of thrombus assembly in a living mouse by confocal and widefield intravital microscopy,”

J. Thromb. Haemost., 1 60

–68

(2003). Google Scholar

S. Proske,

B. Vollmar, and

M. D. Menger,

“Microvascular consequences of thrombosis in small venules: an in vivo microscopic study using a novel model in the ear of the hairless mouse,”

Thromb. Res., 98 491

–498

(2000). 0049-3848 Google Scholar

K. R. Forrester,

C. Stewart,

J. Tulip,

C. Leonard, and

R. C. Bray,

“Comparison of laser speckle and laser Doppler perfusion imaging: measurement in human skin and rabbit articular tissue,”

Med. Biol. Eng. Comput., 40 687

–697

(2002). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02345307 0140-0118 Google Scholar

Y. Piederriere,

J. Cariou,

Y. Guern,

G. Le Brun,

B. Le Jeune,

J. Lotrian,

J. F. Abgrall, and

M. T. Blouch,

“Evaluation of blood plasma coagulation dynamics by speckle analysis,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 9

(2), 408

–412

(2004). https://doi.org/10.1117/1.1645799 1083-3668 Google Scholar

G. C. White,

“The partial thromboplastin time: defining an era in coagulation,”

J. Thromb. Haemost., 1 2267

–2270

(2003). Google Scholar

C. W. Whitten and

P. E. Greilich,

“Thromboelastography: past, present, and future,”

Anesthesiology, 92 1223

–1225

(2000). 0003-3022 Google Scholar

G. E. Jarvis,

“Platelet aggregation: turbidimetric measurements,”

Methods Mol. Biol., 272 65

–76

(2004). 1064-3745 Google Scholar

P. C. Malone and

P. S. Agutter,

“The aetiology of deep venous thrombosis,”

QJM, 99 581

–593

(2006). 1460-2725 Google Scholar

R. K. Jain,

“Determinants of tumor blood flow: a review,”

Cancer Res., 48 2641

–2658

(1988). 0008-5472 Google Scholar

W. M. Chilian,

K. C. Dellsperger,

S. M. Layne,

C. L. Eastham,

M. A. Armstrong,

M. L. Marcus, and

D. D. Heistad,

“Effects of atherosclerosis on the coronary microcirculation,”

Am. J. Physiol., 258 H529

–539

(1990). 0002-9513 Google Scholar

H. M. Spronk,

D. van der Voort, and

H. Ten Cate,

“Blood coagulation and the risk of atherothrombosis: a complex relationship,”

Thromb. J., 2 12

(2004). Google Scholar

K. G. Mann,

“Adding the vessel wall to Virchow’s triad,”

J. Thromb. Haemost., 4 58

–59

(2006). Google Scholar

H. Cheng,

Q. Luo,

S. Zeng,

S. Chen,

J. Cen, and

H. Gong,

“Modified laser speckle imaging method with improved spatial resolution,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 8 559

–564

(2003). https://doi.org/10.1117/1.1578089 1083-3668 Google Scholar

P. Li,

S. Ni,

L. Zhang,

S. Zeng, and

Q. Luo,

“Imaging cerebral blood flow through the intact rat skull with temporal laser speckle imaging,”

Opt. Lett., 31 1824

–1826

(2006). https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.31.001824 0146-9592 Google Scholar

P. Zakharov,

A. Volker,

A. Buck,

B. Weber, and

F. Scheffold,

“Quantitative modeling of laser speckle imaging,”

Opt. Lett., 31 3465

–3467

(2006). https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.31.003465 0146-9592 Google Scholar

|