|

|

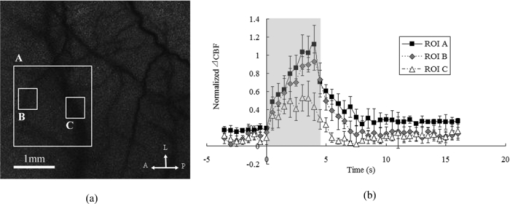

1.IntroductionHypothermia occurs in many situations in life, e.g., exposure to cold environmental temperature, drowning, anesthesia, and cardiac surgery. Although a series of physiological changes following hypothermia is considered life threatening, the cooling procedure has been applied in the neuroscience critical care unit as neuroprotection since the early 1950s.1, 2 Hypothermia is one of the most studied and promising neuroprotective approaches recommended by the Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable.3, 4 Although the precise mechanisms of hypothermic neuroprotection are still unclear, the preservation of brain adenosine triphosphate (ATP) supply following the decrease in metabolism plays an important role.5 Several metabolic biochemical processes are also disturbed by hypothermia: the release of amino acids6 and the formation of excitatory neurotransmitters, hydroxyl radicals,7 and nitric oxide.8 These processes are linked to the reduction of neuronal activity9 and the mediation of coupling brain activity to cerebral blood flow (CBF).10 Nevertheless, the effect of hypothermia on the spatiotemporal neurovascular response to functional stimulation has not been investigated well. Investigating the coupling between vascular responses and functional activations under hypothermia will help 1. further understand the neurovascular coupling involved in the thermoregulation of the brain and 2. monitor the neuronal function in clinical therapeutic hypothermia. Laser speckle imaging (LSI)11, 12 of neurovascular coupling has gained considerable importance in both clinical13 and laboratory settings14 because of its advantage in spatiotemporal resolution over other methods, including conventional laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF),15 and new techniques such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography. In this study, we used LSI to investigate neurovascular coupling after hindpaw electrical stimulation under hypothermia. Somatosensory stimulation was delivered with current pulses (i.e., 5 Hz, 2.5 mA, and 0.3 ms) for 4 s under normothermia (37°C) or hypothermia (32°C). Using registered laser speckle contrast analysis (rLASCA)16 and temporal clustering analysis (TCA), we obtained the spatiotemporal profile of the functional activation altered by hypothermia. LSI bridges the gap between neuronal activity and vascular studies with high spatiotemporal resolution, and facilitates the study of functional organization of cortical microcirculation and the adaptive regulation of CBF triggered by physiologic or pathologic stimulus. 2.Materials and Methods2.1.Animal PreparationEight male Sprague-Dawley rats (270 ± 20g, Slac Laboratory Animal, Shanghai, China) were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (60 mg/kg, IP). The animals were constrained in a stereotaxic frame (Benchmark DeluxeTM, MyNeurolab.com, St. Louis, Missouri) during the experiment. Rectal temperature was monitored and maintained at 37.0 ± 0.2°C with a heating pad and DC control module (FHC Inc., Bowdoinham, Maine). Blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR) of each rat were continuously monitored by the tail-cuff method using an automatic sphygmomanometer (Softron BP-98A system, Softron Co., Tokyo, Japan). A midline incision was made on the scalp, and tissues were cleaned to expose the surface of the skull with a scalpel. An ∼8×5 mm2 cranial window over the right somatosensory cortex was thinned to translucency by a high-speed dental drill (SDE-H37L, Marathon, Korea) with a 1.6 mm burr (Dentsply, Switzerland). Saline was used for cooling during the smoothing. Glycerol was used to reduce the specular reflections and improve the optical clearing.17 2.2.Electrical Hindpaw StimulationHindpaw stimulation was carried out by a programmed stimulator (YC-2, Cheng Yi, China) using two needle electrodes subcutaneously inserted. Each stimulation block involved 10 sequential trials. Each trial consisted of baseline (4 s), stimulation [4 s, rectangular constant current pulses (2.5 mA, 0.3 ms, 5 Hz)], and post-stimulus period (12 s). The minimum of the intertrial interval was 60 s. 2.3.Hypothermia ProcedureThe experimental protocols, approved by the animal care and usage committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, include normothermia, cooling, and moderate hypothermia sessions. After the surgical preparation, temperature was kept stable at 37 ± 0.2°C for 10 min, and stimulations to the left hindpaw were performed every minute. Hypothermia was induced by swabbing the rat's skin with an alcohol pad under an electric fan, as done in previous literature.18, 19 When the temperature was close to 32.5°C, the animal was allowed to cool down passively until the target temperature was reached. The entire cooling procedure took about 40 min. The temperature was then maintained at 32 ± 0.5°C using a feedback-controlled heating pad. During hypothermia, the hindpaw stimulations were delivered in the same way as in the normothermic stage. After the experiments, the animals were euthanized by an overdose of pentobarbital. 2.4.Imaging ProcedureThe laser speckle images (696×512 pixels) were acquired at 23 fps (exposure time T = 5 ms) with a 12-bit CCD camera (Pixelfly QE, Cooke, USA) mounted on a trinocular stereo microscope (XYH-05, Yongheng, Shanghai, China) over the thinned skull. A laser diode (635 ± 2 nm, 10 mW, Model KL5650, Forward Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was used to illuminate the region of interest (ROI). In each trial, we recorded 460 consecutive frames (i.e., 20 s) of speckle images. The stimulation was programmed to start at the fifth second. 2.5.Data Processing2.5.1.Registering the laser speckle imaging dataTo suppress noises due to respiration, heart beating, or both, we first aligned the raw LSI images by the rLASCA method proposed by our group.16 After the raw speckle images were registered with a 3×3 convolution kernel, normalized correlation metric, and cubic B-spline interpolator, we constructed the contrast values for the CBF analysis based on the registered images. 2.5.2.Measurement of blood speedThe principle of LSI has been previously described in literature.11, 20, 21 Briefly, when a highly coherent laser source illuminates a rough surface or a medium that contains moving particles, e.g., blood cells, the interference of the reflected or scattered light results in a granular pattern known as speckle. The most common measure for the speckle pattern related to the speed of the scattering particles is the laser speckle contrast analysis (LASCA),11 which is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation (SD) to the mean intensity in a small region of the image.22 Each raw image was scanned with a sliding window (5×5 pixels) to calculate the speckle contrast, ensuring the sufficiently accurate estimation of speckle contrast with a limited cost of spatial resolution. In the case of blood flow, speckle contrast K s is theoretically linked to the speed by Eq. 1[TeX:] \documentclass[12pt]{minimal}\begin{document}\begin{equation} K_s = \frac{{\sigma _S }}{{\left\langle I \right\rangle }} = \beta ^{1/2} \left\{ {\frac{{\tau _c }}{T} + \frac{{\tau _c^2 }}{{2T^2 }}\left[ {\exp \left({ - \frac{{2T}}{{\tau _c }}} \right) - 1} \right]} \right\}^{1/2}, \end{equation}\end{document}All images were filtered with a Gaussian matrix (half width = 5 pixels) to remove the spatial noises. Contrast values for every 11 frames of consecutive speckle images (∼0.5 s) were averaged to obtain one blood flow image (C s). To increase the signal-to-noise ratio further, we used the average of C s over 10 trials to analyze the CBF change. All image processing was carried out in Matlab (Mathworks, Massachusetts). 2.5.3.Original temporal clustering analysis methodTo analyze the spatiotemporal profile of brain activations, previous studies were usually based on a priori assumptions of the temporal activation patterns. Liu 27 and Gao 28 proposed TCA to detect the time windows of the maximal brain responses in fMRI. In this study, TCA was used to identify the pattern of brain activation regardless of anatomical variances because of the great spatiotemporal heterogeneity in the cortical vasculature.29 Mathematically, TCA converts a high-dimensional space into a one-dimensional space to obtain the number of voxels that reach the maximum of activation at each time point.27 In the current study, we implemented the original TCA (OTCA) method to analyze the LASCA images and detect the stimulus-induced temporal CBF changes under different temperatures. The CBF response was computed within a 2.1×2.1 mm2 (200×200 pixels) ROI over the primary somatosensory hindpaw cortex. The theory of OTCA is detailed in Ref. 27 and 28. Briefly, the dataset C s (t frames with m×n pixels each) can be represented as a two-dimensional matrix C as follows: Eq. 2[TeX:] \documentclass[12pt]{minimal}\begin{document}\begin{equation} {\bf C} = \left({\begin{array}{c@\quad c@\quad c@\quad c@\quad c} C_{s_{1,1}} & C_{s_{1,2}} & C_{s_{1,3}} & \cdots & C_{s_{1,t}} \\ C_{s_{2,1}} & C_{s_{2,2}} & C_{s_{2,3}} & \cdots & C_{s_{2,t}} \\ C_{s_{3.1}} & C_{s_{3,2}} & C_{s_{3,3}} & \cdots & C_{s_{3,t}} \\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ C_{s_{m \times n,1}} & C_{s_{m \times n,2}} & C_{s_{m \times n,3}} & \cdots & C_{s_{m \times n,t}}\\ \end{array}} \right), \end{equation}\end{document}Eq. 3[TeX:] \documentclass[12pt]{minimal}\begin{document}\begin{equation} V_{i,j} = \frac{{| {C_{i,j} - C_{i,0} } |}}{{C_{i,0} }}(1 \le i \le m \times n,1 \le j \le t). \end{equation}\end{document}Eq. 4[TeX:] \documentclass[12pt]{minimal}\begin{document}\begin{equation} W_{i,j} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{c@\quad c} {1,} & {\begin{array}{*{20}c} {\it if}\;{V_{i,j} = \max \left\{ {V_{i,1},V_{i,2},V_{i,3}, \ldots,V_{i,t} } \right\}} & \\[5pt] \end{array}} \\ {0,} & {otherwise} \\ \end{array}} \right.. \end{equation}\end{document}2.6.Statistical AnalysisStatistical analysis was carried out with SPSS 15.0. Paired t-tests were used to analyze the significance of the differences in both response peak and duration between normothermic and hypothermic stages. The differences in the maximum activation area and peak CBF changes between normothermic and hypothermic phases were also analyzed by the same test. p < 0.05 implies a statistically significant difference. The tables and figures show the mean with SD. 3.ResultsThe vital physiological parameters used in the experiments are listed in Table 1. Both HR and BP significantly dropped under hypothermia. Fig. 6Blood flow change in rat's primary somatosensory cortex under hindpaw stimulation. Three ROI are selected for analyzing the CBF changes in different vessels; i.e., (a) whole activated area (ROI A) with two subregions for the capillary bed and arteriole (ROI B) and venule (ROI C). The CBF change in each rat is normalized by the maximum value of ROI B. The error bars represent the standard deviation. (b) Relative CBF changes in ROI. A, anterior; P, posterior; L, lateral.  Table 1HR and BP under normothermia and hypothermia. (Data are presented as mean ± SD; *: paired t-test with hypothermia, P < 0.05.)

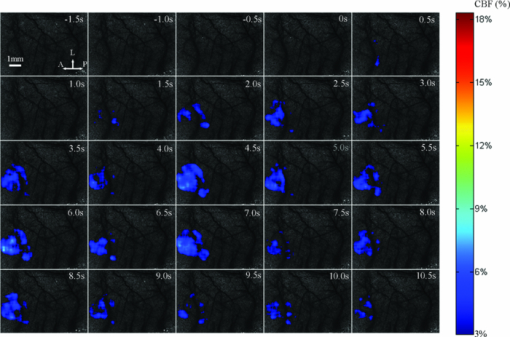

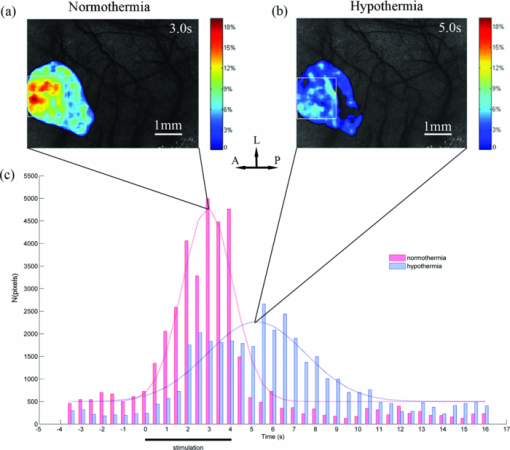

3.1.Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging of Cerebral Blood Flow under Functional StimulationFigure 1 illustrates the spatiotemporal changes in CBF averaged over 10 trials with 4 s hindpaw stimulation for one animal under normothermia (37°C). The images are shown at 0.5 s intervals, indicating an increase in the CBF approximately 1 s after the stimulus onset. To avoid the influence from small noises-derived fluctuations, only the CBF changes higher than 3% were overlaid over the speckle contrast images to show the spatial relationship between CBF change and cortical vascular structure. A prominent increase in CBF was detected around the 3 s post-stimulus onset, lasting for ∼3 s. Fig. 1Relative changes in CBF response to 4 s hindpaw stimulation in a typical animal under normothermia (37°C). The CBF changes higher than 3% are overlaid over the vasculature derived by speckle contrast images. Each image represents a 500 ms interval. A, anterior; P, posterior; L, lateral.  Figure 2 exhibits the spatiotemporal evolution of the CBF response to the same stimulation under hypothermia (32°C) for the same animal in Fig. 1. There was a delay in the response peak under hypothermia compared with normothermia. The CBF response peak occurred at nearly 4.5 s post-stimulus onset and was followed by a relatively more delayed and longer (∼5 s after the stimulation) recovery under hypothermia. Moreover, a smaller activated area and a lower CBF change under hypothermia were observed compared with those under normothermia. 3.2.Time Courses of the Functional Activation under Different TemperaturesFigure 3 demonstrates the temporal profile of the functional activation under normothermia (37°C) and hypothermia (32°C) by the TCA method. To suppress the random noise caused by the trial and subject variations, the temporal clusters were pooled from 80 trials for eight rats. Fig. 3Spatiotemporal CBF changes response to the hindpaw stimulation under normothermia (37°C) and hypothermia (32°C). (a) Peak relative CBF change response to the hindpaw stimulation occurring 3 s after the stimulus onset under normothermia. (b) Peak relative CBF change response to the hindpaw stimulation occurring 5 s after the stimulus onset under hypothermia. The white boxes in (a) and (b) denote the ROI in measuring the spatial properties of the brain activation. (c) Temporal cluster of CBF response to the hindpaw stimulation. The TCA results are fitted with the Gaussian function (dotted line) used to detect the activation time window. For normothermia (37°C) (the red part), a time window (1.5 to 4.3 s) centered at tmax (2.9 s) is determined by the Gaussian fitting (r = 0.9511). For hypothermia (32°C) (the blue part), a time window (2.5 to 7.9 s) centered at tmax (5.2 s) is estimated by the Gaussian fitting (r = 0.9269). A, anterior; P, posterior; L, lateral.  To detect the activation peaks, the TCA results [Fig. 3c] were fitted with the Gaussian function [i.e., N(t) in Eq. 5] Eq. 6[TeX:] \documentclass[12pt]{minimal}\begin{document}\begin{equation} N(t) = \frac{A}{{\sqrt {2\pi \sigma ^2 } }}e^{ - \frac{{(t - t_{\max })^2 }}{{2\sigma ^2 }}} + B, \end{equation}\end{document}Eq. 7[TeX:] \documentclass[12pt]{minimal}\begin{document}\begin{equation} R_d = {\it FWHM} = 2\sqrt {2\ln 2} \sigma \approx 2.3548\sigma.\end{equation}\end{document}Table 2 lists the statistical results of the response peak and duration under different temperatures averaged across eight animals based on 10 trials in each subject. The time to response peak was around 2.6 ± 0.4 s post-stimulus onset at 37°C, which was significantly delayed to 5.2 ± 1.2 s at 32°C (P < 0.05) under hypothermia. Furthermore, the response duration under normothermia (2.6 ± 0.6 s) was significantly prolonged under hypothermia (5.3 ± 2.3 s) (P < 0.05). Table 2Spatial and temporal responses to 4 s hindpaw stimulation under normothermia and hypothermia (n = 8) in the aspect of relative CBF change. The time scale starts from the onset of a stimulus. (Data are presented as mean ± SD; *: paired t-test with hypothermia, P < 0.05.)

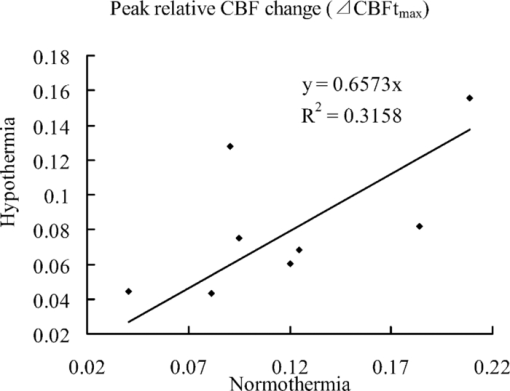

To show how much the CBF is correlated with the temperature, we present the scatter plots of the response peak [tmax, Fig. 4a] and response duration [Rd, Fig. 4b] under hypothermia versus normothermia for each animal. Linear regression analysis was performed to determine the correlation. The regression line in each plot was calculated according to y = ax, with y being the response values at hypothermia and x being the values at normothermia. Close correlations were observed between the responses (both tmax and Rd) under hypothermia and those under normothermia according to the correlation coefficients (tmax: r = 0.71; Rd: r = 0.82) with very similar slopes (tmax: s = 1.9271; Rd: s = 2.0955). 3.3.Effects of Temperature on Spatial ActivationThe OTCA method does not directly provide the spatial details of the cortical response. To investigate the spatial properties of the brain activation under hypothermia, a ROI (150×150 pixels) window, which covered more than 60% of the pixels with CBF change above the half maximum of the response peak by OTCA, was defined. The activation area, i.e., pixels with CBF above the half maximum within the ROI,30 was used to quantify the CBF response. Figure 3 illustrates the CBF change at tmax under normothermia [Fig. 3a] and hypothermia [Fig. 3b] for one animal. Table 2 shows the statistical results from eight animals, i.e., the activated area at tmax under normothermia is significantly larger than that under hypothermia (P < 0.05). There is also a statistically significant decrease in the peak relative CBF change ( [TeX:] $\Delta {\it CBF}_{t_{\max } } $ ) from normothermia to hypothermia (P < 0.05). Figure 5 shows the relationship between the [TeX:] $\Delta {\it CBF}_{t_{\max } } $ under normothermia and that under hypothermia. An approximately linear correlation is observed for [TeX:] $\Delta {\it CBF}_{t_{\max } } $ between two temperatures (r = 0.56). Fig. 5Scatter plots showing the correlation of the peak relative CBF change ( [TeX:] $\Delta {\it CBF}_{t_{\max } } $ ) between normothermic and hypothermic stages. The best-fit line and correlation coefficient (R2) values represent the results of the linear regression analysis.  Taking advantage of the high spatial resolution of LSI, we were able to find the different blood flow changes in a rat's primary somatosensory cortex through hindpaw stimulation in different vessels from six rats with distinguishable vasculature (Fig. 6). The CBF changes in the venules (ROI C in Fig. 6) were less prominent than those in the capillary bed and arteriolar vessels (ROI B in Fig. 6), in accordance with the different hemoglobin dynamics in the arterioles, capillaries, and venules.31 The arterioles and venules were manually segmented by the anatomical features. 4.Discussion4.1.Temporal Characteristics of Functional ActivationUnder hypothermia, a significant delay of response was observed (P < 0.05), and the CBF recovered to the normal level (P < 0.05) more slowly. Under normothermia, CBF started to increase at ∼1 s and reached the peak at 2.6 ± 0.4 s after the stimulation onset, consistent with the reported hemodynamic changes during both forepaw32 and hindpaw33 stimulations in rats by LDF and LSI, respectively. In modeling the stimuli-induced hemodynamic responses, the Gaussian function has been proven to be a more natural and flexible mathematical model than the Poisson or Gamma function.34 It fits well with the data from optical intrinsic imaging and fMRI, especially in characterizing the time delay between the hemodynamic response and neural activities.34, 35 The correlation coefficients of the Gaussian fitting of our TCA data were compared between hypothermia and normothermia (0.9511 versus 0.9269), implying that the hemodynamic response still maintains the same temporal statistic model under hypothermia. The slower neuronal response under hypothermia may be caused by the suppression of the conduction in the peripheral nerve and spinal pathways36 under low temperature. Thus, it increases the latencies and prolongs the durations of the excitatory postsynaptic potentials evoked by electrical stimulation.37 The molecular mechanism of such delayed and prolonged response under hypothermia is probably related to the decreased release of neurotransmitters such as glutamate.2 4.2.Spatial Characteristics of Functional ActivationAnother interesting question is whether hypothermia could alter the activity-induced neurovascular or neurometabolic coupling. Our LSI results show that both the activation area and [TeX:] $\Delta {\it CBF}_{t_{\max } } $ , in response to the functional hindpaw stimulation, were significantly reduced under hypothermia (P < 0.05). However, previous results from Royl 38 show only the magnitude, and not the temporal features (i.e., latency and duration), of the relative CBF change under hypothermia that could have been caused by the limited spatial resolution of LDF. Fixed ROI chosen by traditional LDF would bias the relative CBF change because of the heterogeneous vasculature. OTCA solves this problem by defining the ROI dependent on the response results, which, therefore, provides higher spatiotemporal resolution of the functional representation of the CBF change without prior assumptions or knowledge on the spatiotemporal patterns of cortical activations. Note that the temporal profile of our CBF change by LSI is more consistent with Royl's finding on the electrophysiological response to somatosensory stimulation during hypothermia, i.e., the decreased amplitude and delayed peak time of somatosensory evoked potential (SEP), than the CBF results by the LDF method.38 Combining the results with other electroencephalogram (EEG) findings, e.g., a decrease in EEG amplitude and a shift of EEG waves to lower frequencies under hypothermia conditions,39 we can conclude that the neurovascular coupling is preserved during moderate hypothermia to some extent. Most biological processes governing neuronal activity have a temperature coefficient (Q10) between 2 and 3.37 Q10 is calculated as follows: Eq. 8[TeX:] \documentclass[12pt]{minimal}\begin{document}\begin{equation} Q_{10} = \left({\frac{{R_2 }}{{R_1 }}} \right)^{{{10}}/{{t_2 - t_1 }}}, \end{equation}\end{document}Furthermore, the reduced activation area and relative CBF change under hypothermia may imply that a smaller number of neurons are involved in functional activation. Nevertheless, considering the prolonged response duration under hypothermia, the total energy demand under hypothermia may not change compared with that under normothermia. The spatial pattern of the vascular hemodynamic response is closely related to the neuronal function. So far, capillary responses to somatosensory stimulus have not been fully understood. Taking advantage of the high spatial resolution of LSI, we were able to investigate the hemodynamic response to somatosensory stimulus in a specific vascular compartment. Compared with the CBF changes in venules, the changes in arterioles and capillaries are more prominent. Such a different CBF response in the arterioles and capillaries could be explained by the received vasodilatory signals in the receptors on capillaries (or capillary dilatation), which then propagate along the vessels to the upstream arteriolar smooth muscle to regulate the blood flow to the neuropil.42, 43, 44 Therefore, our results suggest that large venules should be avoided when LDF is used to measure the activity-dependent CBF changes. 4.3.Effects of AnestheticsLike most studies on hypothermia, the animals in this study had to be anesthetized throughout the experiments, which could not prevent anesthesia-induced hypothermic hypometabolism. Anesthesia is also unavoidable in clinical hypothermic therapeutics. CBF can be decreased by pentobarbital, according to experimental and clinical studies,45 although such pentobarbital-induced reduction of CBF is homogeneous.46 The extent to which the accumulation of anesthetics can influence the response of CBF under functional stimulation is still unclear. Although no direct evidence exists to prove that the stimulus-induced CBF change is steady during anesthesia, in a study on rats on the effect of anesthetics on functional metabolic coupling in somatosensory stimulation, the regional cerebral metabolic rate of glucose is preserved under pentobarbital anesthesia.47 In addition, the results of Royl 38 did not show significant changes in SEP or CMRO2 under functional stimulation during 3 h of normothermia following the same anesthesia protocols. Nevertheless, a stable anesthesia during the experiment is definitely helpful. 5.ConclusionsThe spatiotemporal neurovascular coupling in brain activity is crucial in understanding the mechanism of brain function under different physiological and pathological conditions. We demonstrated LSI as a promising and quantitative functional imaging method with high spatiotemporal resolution and minimal invasiveness. In particular, using a combination of the two-dimensional LSI technique and TCA method, we were able to detect the high resolution of spatiotemporal CBF changes in response to hindpaw stimulation under hypothermia without any assumed knowledge about the neural activation pattern. The main findings of this study are as follows. 1. Moderate hypothermia delays and prolongs functional activation in the aspect of the relative CBF response, but the activity-induced neuronal activity is preserved. 2. Moderate hypothermia attenuates the maximal activation area and the peak relative CBF change. 3. Capillaries and arterioles are the major contributors in the vascular responses to functional activation. AcknowledgmentsWe thank Ran Luo, Shengfa Zhang, and Jiangwa Xing for their help in the animal experiments. This work was supported by NSFC (Grant No. 81071192). ReferencesS. A. Bernard and

M. Buist,

“Induced hypothermia in critical care medicine: a review,”

Crit. Care Med., 31

(7), 2041

–2051

(2003). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000069731.18472.61 Google Scholar

K. R. Diller and

L. Zhu,

“Hypothermia therapy for brain injury,”

Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng., 11 135

–162

(2009). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-bioeng-061008-124908 Google Scholar

P. Bath,

“Re: Stroke Therapy Academic Industry Roundtable II (STAIR-II),”

Stroke, 33

(2), 639

–640

(2002). Google Scholar

V. E. O’Collins, M. R. Macleod, G. A. Donnan, L. L. Horky, B. H. van der Worp, and

D. W. Howells,

“Experimental treatments in acute stroke,”

Ann. Neurol., 59 467

–477

(2006). https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20741 Google Scholar

M. Erecinska, M. Thoresen, and

I. A. Silver,

“Effects of hypothermia on energy metabolism in mammalian central nervous system,”

J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab., 23

(5), 513

–530

(2003). https://doi.org/10.1097/01.WCB.0000066287.21705.21 Google Scholar

K. Nakashima and

M. M. Todd,

“Effects of hypothermia on the rate of excitatory amino acid release after ischemic depolarization,”

Stroke, 27

(5), 913

–918

(1996). https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.27.5.913 Google Scholar

R. Busto, M. Y. Globus, W. D. Dietrich, E. Martinez, I. Valdes, and

M. D. Ginsberg,

“Effect of mild hypothermia on ischemia-induced release of neurotransmitters and free fatty acids in rat brain,”

Stroke, 20

(7), 904

–910

(1989). https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.20.7.904 Google Scholar

T. M. Hemmen and

P. D. Lyden,

“Induced hypothermia for acute stroke,”

Stroke, 38

(2), 794

–799

(2007). https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000247920.15708.fa Google Scholar

J. S. Beckman and

W. H. Koppenol,

“Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly,”

Am. J. Physiol.: Cell Physiol., 271

(5), C1424

–C1437

(1996). Google Scholar

C. Iadecola,

“Regulation of the cerebral microcirculation during neural activity: is nitric oxide the missing link,”

Trends Neurosci., 16

(6), 206

–214

(1993). https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-2236(93)90156-G Google Scholar

J. D. Briers, G. Richards, and

X. W. He,

“Capillary blood flow monitoring using laser speckle contrast analysis (LASCA),”

J. Biomed. Opt., 4 164

–175

(1999). https://doi.org/10.1117/1.429903 Google Scholar

A. F. Fercher and

J. D. Briers,

“Flow visualization by means of single-exposure speckle photography,”

Opt. Commun., 37

(5), 326

–330

(1981). https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-4018(81)90428-4 Google Scholar

N. Hecht, J. Woitzik, J. P. Dreier, and

P. Vajkoczy,

“Intraoperative monitoring of cerebral blood flow by laser speckle contrast analysis,”

Neurosurg. Focus., 27

(4), E11

–E11

(2009). https://doi.org/10.3171/2009.8.FOCUS09148 Google Scholar

E. M. C. Hillman,

“Optical brain imaging in vivo: techniques and applications from animal to man,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 12

(5), 051402

(2007). https://doi.org/10.1117/1.2789693 Google Scholar

M. Wintermark, M. Sesay, E. Barbier, K. Borbely, W. P. Dillon, J. D. Eastwood, T. C. Glenn, C. B. Grandin, S. Pedraza, and

J. F. Soustiel,

“Comparative overview of brain perfusion imaging techniques,”

Stroke, 36

(9), e83

–e99

(2005). https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000177884.72657.8b Google Scholar

P. Miao, A. Rege, N. Li, N. Thakor, and

S. Tong,

“High resolution cerebral blood flow imaging by registered laser speckle contrast analysis,”

IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., 57

(5), 1152

–1157

(2010). https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2009.2037434 Google Scholar

V. Tuchin,

“Optical clearing of tissues and blood using the immersion method,”

J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys., 38 2497

–2518

(2005). https://doi.org/10.1088/0022-3727/38/15/001 Google Scholar

A. Takasu, S. W. Stezoski, J. Stezoski, P. Safar, and

S. A. Tisherman,

“Mild or moderate hypothermia, but not increased oxygen breathing, increases long-term survival after uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock in rats,”

Crit. Care Med., 28

(7), 2465

–2474

(2000). https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-200007000-00047 Google Scholar

S. H. Kim, S. W. Stezoski, P. Safar, A. Capone, and

S. Tisherman,

“Hypothermia and minimal fluid resuscitation increase survival after uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock in rats,”

J. Trauma: Inj., Infect., Crit. Care, 42

(2), 213

–222

(1997). https://doi.org/10.1097/00005373-199702000-00006 Google Scholar

J. W. Goodman,

“Some fundamental properties of speckle,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am., 66

(11), 1145

–1150

(1976). https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSA.66.001145 Google Scholar

J. C. Dainty, Laser Speckle and Related Phenomena, Springer-Verlag, Berlin and New York

(1975). Google Scholar

A. Dunn, H. Bolay, M. Moskowitz, and

D. Boas,

“Dynamic imaging of cerebral blood flow using laser speckle,”

J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab., 21

(3), 195

–201

(2001). https://doi.org/10.1097/00004647-200103000-00002 Google Scholar

D. A. Boas and

A. K. Dunn,

“Laser speckle contrast imaging in biomedical optics,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 15

(1), 011109

(2010). https://doi.org/10.1117/1.3285504 Google Scholar

R. Bandyopadhyay, A. Gittings, S. Suh, P. Dixon, and

D. Durian,

“Speckle-visibility spectroscopy: a tool to study time-varying dynamics,”

Rev. Sci. Instrum., 76 093110

(2005). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2037987 Google Scholar

J. C. Ramirez-San-Juan, R. Ramos-GarcYa, I. Guizar-Iturbide, G. MartYnez-Niconoff, and

B. Choi,

“Impact of velocity distribution assumption on simplified laser speckle imaging equation,”

Opt. Express, 16

(5), 3197

–3203

(2008). https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.16.003197 Google Scholar

D. D. Duncan and

S. J. Kirkpatrick,

“Can laser speckle flowmetry be made a quantitative tool,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 25

(8), 2088

–2094

(2008). https://doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.25.002088 Google Scholar

Y. Liu, J. H. Gao, H. L. Liu, and

P. T. Fox,

“The temporal response of the brain after eating revealed by functional MRI,”

Nature, 405

(6790), 1058

–1062

(2000). https://doi.org/10.1038/35016590 Google Scholar

S. H. Yee and

J. H. Gao,

“Improved detection of time windows of brain responses in fMRI using modified temporal clustering analysis,”

Magn. Reson. Imaging, 20

(1), 17

–26

(2002). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0730-725X(02)00484-8 Google Scholar

R. Steinmeier, I. Bondar, C. Bauhuf, and

R. Fahlbusch,

“Laser Doppler flowmetry mapping of cerebrocortical microflow: characteristics and limitations,”

Neuroimage, 15

(1), 107

–119

(2002). https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2001.0943 Google Scholar

W. Lau, S. Tong, and

N. V. Thakor,

“Spatiotemporal characteristics of low-frequency functional activation measured by laser speckle imaging,”

IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng., 13

(2), 179

–185

(2005). https://doi.org/10.1109/TNSRE.2005.847371 Google Scholar

E. Hillman, A. Devor, M. B. Bouchard, A. K. Dunn, G. W. Krauss, J. Skoch, B. J. Bacskai, A. M. Dale, and

D. A. Boas,

“Depth-resolved optical imaging and microscopy of vascular compartment dynamics during somatosensory stimulation,”

Neuroimage, 35

(1), 89

–104

(2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.11.032 Google Scholar

T. Durduran, M. G. Burnett, G. Yu, C. Zhou, D. Furuya, A. G. Yodh, J. A. Detre, and

J. H. Greenberg,

“Spatiotemporal quantification of cerebral blood flow during functional activation in rat somatosensory cortex using laser-speckle flowmetry,”

J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab., 24

(5), 518

–525

(2004). https://doi.org/10.1097/00004647-200405000-00005 Google Scholar

S. A. Sheth, M. Nemoto, M. Guiou, M. Walker, N. Pouratian, and

A. W. Toga,

“Linear and nonlinear relationships between neuronal activity, oxygen metabolism, and hemodynamic responses,”

Neuron, 42

(2), 347

–355

(2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00221-1 Google Scholar

J. C. Rajapakse, F. Kruggel, J. M. Maisog, and

D. Y. Von Cramon,

“Modeling hemodynamic response for analysis of functional MRI time-series,”

Hum. Brain Mapp, 6

(4), 283

–300

(1998). https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1998)6:4<283::AID-HBM7>3.0.CO;2-# Google Scholar

M. Svensen, F. Kruggel, and

D. Y. Von Cramon,

“Probabilistic modeling of single-trial fMRI data,”

IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, 19

(1), 25

–35

(2002). https://doi.org/10.1109/42.832957 Google Scholar

R. D. Dripps and

R. W. Virtue,

“The physiology of induced hypothermia. Proceedings of a symposium,”

Anesthesiology, 19

(1), 118

–119

(1958). https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-195801000-00047 Google Scholar

E. A. Kiyatkin,

“Brain hyperthermia as physiological and pathological phenomena,”

Brain Res. Rev., 50

(1), 27

–56

(2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.04.001 Google Scholar

G. Royl, M. Füchtemeier, C. Leithner, D. Megow, N. Offenhauser, J. Steinbrink, M. Kohl-Bareis, U. Dirnagl, and

U. Lindauer,

“Hypothermia effects on neurovascular coupling and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen,”

Neuroimage, 40

(4), 1523

–1532

(2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.041 Google Scholar

T. Deboer and

I. Tobler,

“Temperature dependence of EEG frequencies during natural hypothermia,”

Brain Res., 670

(1), 153

–156

(1995). https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-8993(94)01299-W Google Scholar

X. H. Zhu, Y. Zhang, N. Zhang, K. Ugurbil, and

W. Chen,

“Noninvasive and three-dimensional imaging of CMRO2 in rats at 9.4 T: reproducibility test and normothermia/hypothermia comparison study,”

J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab., 27

(6), 1225

–1234

(2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600421 Google Scholar

P. Krafft, T. Frietsch, C. Lenz, A. Piepgras, W. Kuschinsky, K. F. Waschke, and

C. Iadecola,

“Mild and moderate hypothermia ({alpha}-stat) do not impair the coupling between local cerebral blood flow and metabolism in rats editorial comment,”

Stroke, 31

(6), 1393

–1400

(2000). https://doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.31.6.1393 Google Scholar

R. Duelli and

W. Kuschinsky,

“Changes in brain capillary diameter during hypocapnia and hypercapnia,”

J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab., 13

(6), 1025

–1028

(1993). https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.1993.129 Google Scholar

C. Iadecola, G. Yang, T. J. Ebner, and

G. Chen,

“Local and propagated vascular responses evoked by focal synaptic activity in cerebellar cortex,”

J. Neurophysiol., 78

(2), 651

–659

(1997). Google Scholar

A. Villringer, A. Them, U. Lindauer, K. Einhaupl, and

U. Dirnagl,

“Capillary perfusion of the rat brain cortex. An in vivo confocal microscopy study,”

Circ. Res., 75

(1), 55

–62

(1994). Google Scholar

K. S. Hendrich, P. M. Kochanek, J. A. Melick, J. K. Schiding, K. D. Statler, D. S. Williams, D. W. Marion, and

C. Ho,

“Cerebral perfusion during anesthesia with fentanyl, isoflurane, or pentobarbital in normal rats studied by arterial spin-labeled MRI,”

Magn. Reson. Med., 46

(1), 202

–206

(2001). https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1178 Google Scholar

A. Gjedde and

M. Rasmussen,

“Blood-brain glucose transport in the conscious rat: comparison of the intravenous and intracarotid injection methods,”

J. Neurochem., 35

(6), 1375

–1381

(1980). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.1980.tb09012.x Google Scholar

M. Ueki, G. Mies, and

K. A. Hossmann,

“Effect of alpha-chloralose, halothane, pentobarbital and nitrous oxide anesthesia on metabolic coupling in somatosensory cortex of rat,”

Acta Anaesthesiol.Scand., 36

(4), 318

–322

(1992). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.1992.tb03474.x Google Scholar

|