|

|

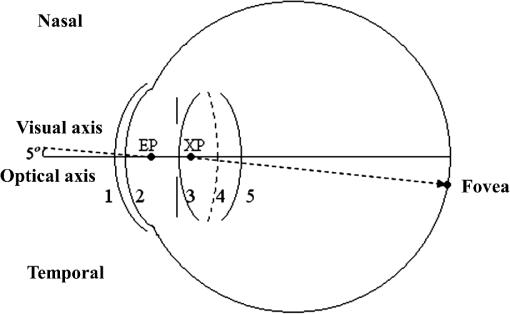

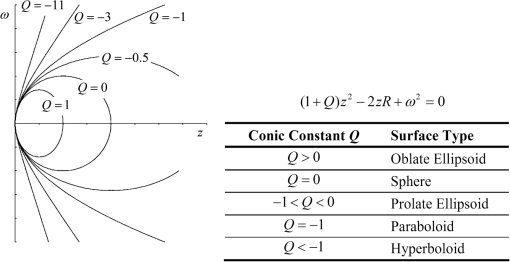

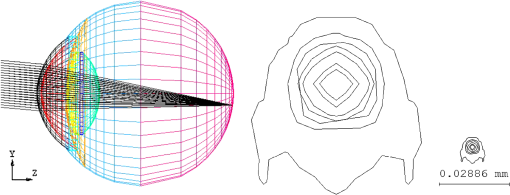

1.IntroductionThe anatomic and optical properties of human eyes have long been important issues in the fields of ophthalmology, optics, and vision science. Accurate modeling of the human eyes provides a powerful tool to predict visual performance and facilitate ophthalmic surgeries. Dozens of schematic eye models mimicking the optical structure of the eye have been proposed since the beginning of the 20th century. Early models by Helmholtz,1 Gullstrand,2 Emsley,3 and Le Grand4 have been widely used for first-order calculations. Due to limited ray-tracing computational power and inadequate biological measurements at the time, these models simplified the optical system of human eyes by reducing the number of ocular surfaces, approximating ocular surfaces with spherical surfaces, or using a homogeneous refractive index for the crystalline lens. As a result, they exhibited departures from experimental data in describing on-axis aberration properties. To increase the consistency with experimental data, aspheric surfaces and a lens with a non-homogeneous refractive index have been incorporated in subsequent models. Asphericities were first introduced to ocular surfaces by Lotmar5 to the anterior surface of the cornea and the posterior surface of the crystalline lens. This model was able to predict the spherical aberration with a homogeneous crystalline lens but required a hypothetic lens with seven shells of stepped refractive indices to describe off-axis aberrations. Navarro et al.6 proposed an accommodation-dependent model with four centered aspheric surfaces, including anterior and posterior surfaces of the cornea and crystalline lens, and were able to reproduce the on-axis optical performance. They also computed the wavelength-dependent refractive indices by using the Herzberger formula to fit the experimental data in chromatic aberration. However, they used a homogeneous crystalline lens and thus limited the applicability in predicting off-axis aberrations. Two approaches have been taken in accounting for the non-homogeneity of the crystalline lens, namely a shell model that has a finite number of concentric shells with stepped refractive indices and a gradient-index (GRIN) model that has a smooth index variation usually described by a set of equations. It has been reported that the non-continuous structure in the crystalline lens generates multiple focal planes,7 and hence a GRIN lens model shows better promise. An adaptive GRIN lens model was first introduced by Blaker;8 since then several models have been proposed to match the biological data measured by ever-advancing technologies. In particular, Liou and Brennan9 performed an extensive search on biometric data to select the ocular parameters in their schematic eye. They incorporated the nasal pupil shift and the visual-axis departure from the optical axis to better resemble the optical realities. They also proposed a GRIN lens model in a parabolic distribution with respect to the axial and radial coordinates. Goncharov and Dainty10 combined Navarro’s model for off-axis aberrations,11 Thibos’ on-axis chromatic model,12 and a GRIN lens model of 4th-order polynomials to construct a wide-field age-dependent schematic eye model. Navarro et al. formulated an adaptive GRIN lens model with concentric conicoid isoindical surfaces13 to include age and accommodation factors.14 These GRIN models can be integrated into existing schematic eyes for visual simulations. Another important factor that affects visual quality is light scattering in the eyes. Light scatter in the ocular structure causes image contrast reductions on fovea, especially when off-axis glare sources are present.15 Scattering occurs at the iris, retina, and ocular interfaces, in the ocular media, and from cataract and normal aging of the crystalline lens. The major contribution owes to the large protein molecules inside the intraocular media. The sources of scatter contributions in the human eye are as follows: the cornea accounts for about 30%, the lens 40%, and the retina approximately 20% in normal individuals.16,17 Also, Van den Berg et al.18 had shown that the iris and sclera also scatter light, with light-colored eyes scattering more than dark-brown eyes. In the crystalline lens, the scattering particle sizes of protein molecules are 1 to 4 microns in diameter,19 which is comparable to the wavelength of visible light. Mie scattering, which has stronger forward scattering and is approximately wavelength-independent, is the dominating process for particles of this size. In virtue of our experiences in solid-state lighting,20–22 we are particularly interested in visual performance under various lighting and display conditions. The scattering properties of ocular media are essential for simulating glare effects on visual contrast sensitivity. Intraocular scattering was first introduced by Navarro23 into schematic eyes but is missing in modern eye models. In order to incorporate intraocular scattering as well as accommodation and age effects, a biometry-based schematic eye model was developed in this research. 2.PrincipleAnatomic and optical data of ocular parameters for the averaged relaxed eye, including radii and asphericities of cornea surfaces, thicknesses between interfaces, refractive indices of ocular media, pupil shift towards the nasal, and visual-axis departure from the optical axis were adopted from the biometric data selected by Liou and Brennan.9 The mathematical GRIN model for crystalline lens was adopted from Navarro et al.14 in order to simulate the age and accommodation effects. As the shape of the crystalline lens changes with age and accommodation, the thickness and radii of curvatures were adopted from Dubbelman et al.24 while the surface asphericities were from Navarro et al.14 Chromatic dispersion models of homogeneous ocular media were constructed by using the Cauchy equations proposed by Atchison and Smith.25 The core and cortex refractive indices of the crystalline lens were modified at particular wavelengths according to the same dispersion model and then used to construct the GRIN model. In order to describe the light scattering behavior in the human eye model, a scattering model in the cornea, crystalline lens, and retina fundus was constructed. The size distribution, volume fraction, and refractive index of the protein molecules inside the normal-aging and cataractous lenses were adopted from Gilliland et al.19 and incorporated into the GRIN lens to simulate volumetric scatters. The retina fundus was considered as a Lambertian surface with reflectance values adopted from Zagers et al.26 Due to the lack of scattering particle data in the cornea, a volumetric scattering model in the cornea was tuned along with the readily-defined scattering models in the crystalline lens and at the retina fundus to match the CIE disability glare formula.27 The optical performance of the human eye model was presented by the point spread function (PSF) for an object at infinity and by the modulation transfer function (MTF) at single and multiple wavelengths. The monochromatic MTF was compared with experimental data from Guirao et al.28 The chromatic optical powers of the real human eye were used to validate the dispersion model. The scattering model was used to simulate the irradiance at the cornea entrance face and the veiling luminance received at the fovea. The ratio of the veiling luminance to the entrance irradiance was then plotted to compare with the CIE disability glare formula. By replacing the transparent lens with a cataractous lens, the disability glare behavior in cataract eyes was predicted. 3.Modeling3.1.Geometric Optical ParametersThe schematic eye model was first developed in CodeV for evaluating PSFs, MTFs, and dispersion properties without the scattering model. The same model was then constructed in ASAP with the scattering model for evaluating glare luminance. Table 1 shows the geometric optical parameters of the human eye model with an unaccommodated crystalline lens at age 40 and Fig. 1 shows the schematic drawing. The visual axis is tilted with respect to the optical axis towards the nasal side by 5 deg.29 Surface 3 consists of the pupil aperture and the anterior surface of the crystalline lens. The pupil is displaced nasally by 0.5 mm30 while the anterior lens surface is still centered on the optical axis. The surface asphericity is described by the conic constant of a conicoid, which is formulated as where is the coordinate on the axis of revolution with the origin at the apex, is the radial distance to the axis, and is the radius of curvature at the apex. Figure 2 shows the surface types with different values of conic constants. The conic constants for surfaces 1, 2, 3, and 5 in Table 1 are fitted values to the empirical data.9,14 Surface 4 is a hypothetic interface of the GRIN lens model as shown in Fig. 3. The radius of curvature and the conic constant for surface 4 are fitted values to the interface where the anterior and posterior concentric conicoid isoindical surfaces intersect. The thickness of the vitreous humor was adjusted so that the paraxial image plane fell on the retina at the wavelength of 555 nm. The corresponding axial length of the schematic eye was 24.32 mm.Table 1Geometric optical parameters of the relaxed human eye model.

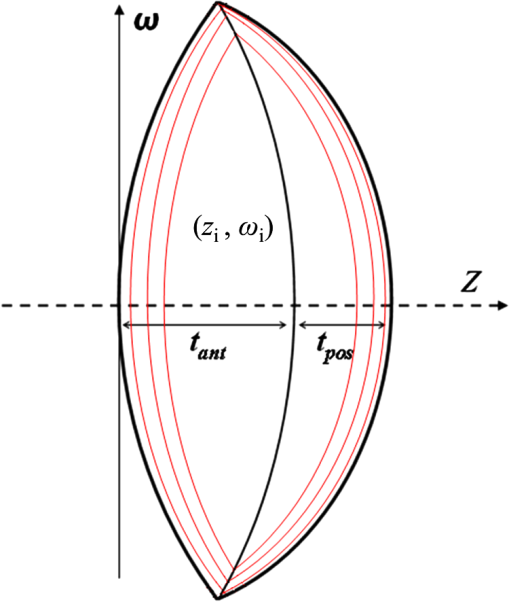

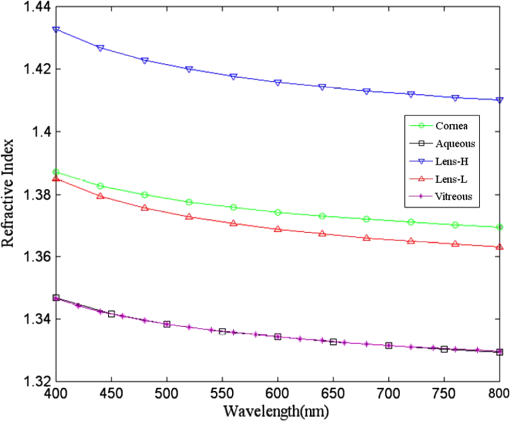

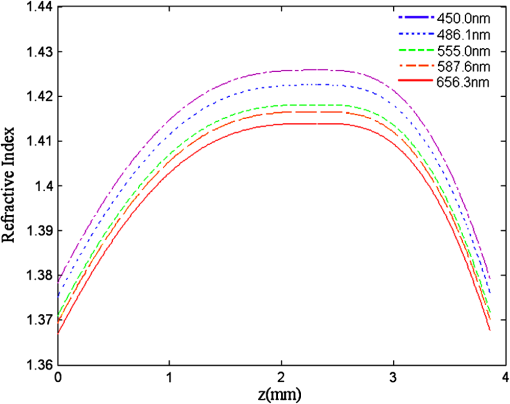

The refractive indices of the homogeneous ocular media, including cornea, aqueous humor, and vitreous humor, were averaged empirical data at the wavelength of 555 nm. The refractive index of the crystalline lens is highest (around 1.418) and slowly varying in the central nucleus and rapidly declining to a lowest value (around 1.371) at the anterior and posterior surfaces.31 The GRIN lens model shown in Fig. 3 consists of concentric conicoid isoindical surfaces. The refractive indices for the anterior and posterior portions are formulated as13 where is the highest refractive index at the lens core at 555 nm and is the difference between the core and cortex refractive indices. is the thickness of the anterior portion and is three-fifths of the total lens thickness ().13 Parameters and are the semi-axes of the conicoid, and controls the shape ( for ellipsoids and for hyperboloids). The semi-axes can be calculated from the apex radius and the conic constant by and . Parameters and move the coordinate origin from the center of the conicoid to the apex, and satisfy the relations and . Parameters and are normalization constants so that the values inside the brackets of Eq. (2) are between 0 and 1. The changes of the lens geometry and the exponent in the GRIN lens model with the age and accommodation factors are listed in Table 2.Table 2Parameter change in the GRIN lens model with age A (in years) and accommodation D (in diopters). 3.2.Chromatic DispersionThe chromatic dispersion properties of ocular media were described by the Cauchy equation with four terms25 as where the corresponding coefficients for each ocular medium are listed in Table 3. For the crystalline lens, only the coefficients for the core (high) and cortex (low) refractive indices are provided. The lens high and low values at 555 nm in Atchison and Smith25 are 1.406 and 1.386, respectively, taken from Gullstrand’s GRIN lens model.2 Their fitted Cauchy equations areTable 3Coefficients of the Cauchy equation for the dispersion model of ocular media.

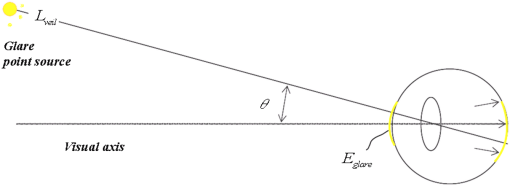

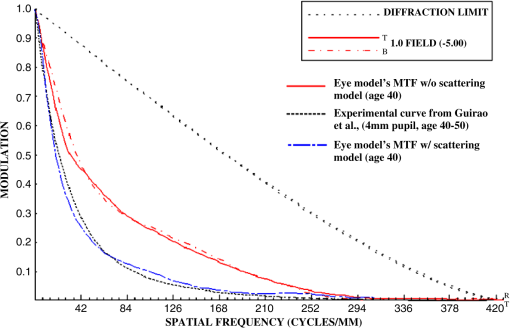

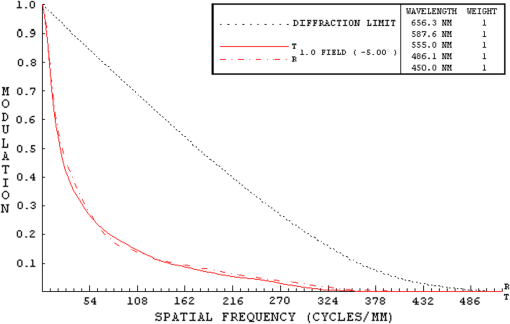

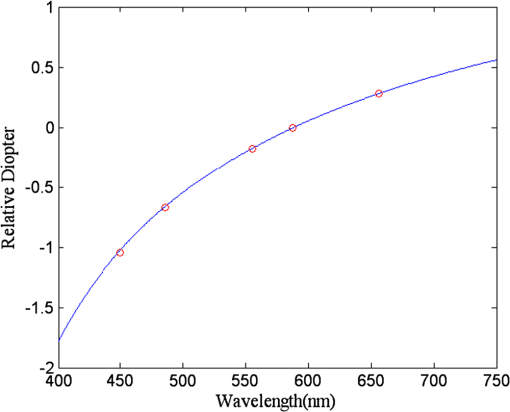

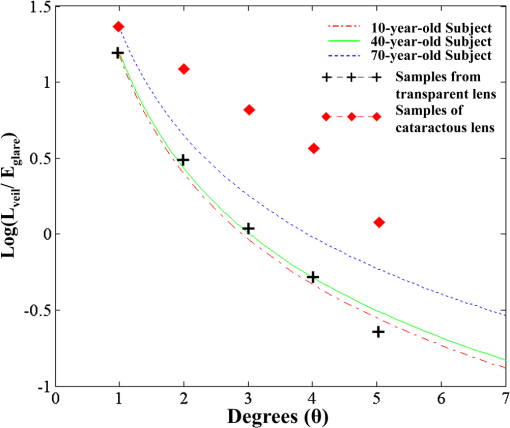

They also found that for a particular ocular medium, the chromatic dispersion in the range of 400 to 900 nm can be obtained by a constant scaling factor for different refractive indices. That is, if is the refractive index used in a particular eye model at a reference wavelength and is the refractive index to be used in another eye model, the refractive index at some other wavelength is then In other words, we can simply scale the Cauchy Eqs. (4a) and (4b) and use and in our model. The coefficients of the scaled Cauchy equations are given in Table 3. At a particular wavelength, the corresponding lens high and low values are used in Eq. (2a) and (2b) to generate the GRIN lens [i.e., and ]. The chromatic optical powers of the eye model are calculated at five wavelengths, 450.0, 486.1, 555.0, 587.6, and 656.3 nm, and compared to the average dispersion properties of physiological human eyes. 3.3.Scattering Model in Human EyesIntraocular light scattering is an optical phenomenon that may strongly affect the visual performance of human eyes. The scatter contributions are approximately 30% from the cornea, 40% from the lens, and 20% from the retina in normal individuals.16,17 The rest are caused by the iris and sclera, with light-colored irises scattering more than dark-brown ones. For simplicity, this study considered a dark iris to eliminate the iris scattering effect. The constructed scattering model of the cornea, lens, and retina fundus are detailed below. 3.3.1.Crystalline lensIntraocular volumetric scattering due to protein molecules in the crystalline lens was modeled by Mie scattering in ASAP. This requires several modeling parameters, including the particle sizes, the equivalent obscuration area fraction, and the particle refractive index. The multilamellar bodies (MLBs) observed by Gilliland et al.19,32,33 in age-related nuclear cataracts were adopted as the scattering particles in the GRIN lens model. The cataractous lenses in their study were from subjects with nuclear sclerosis cataract grade from 1 to 3 based on a 0 to 4 scale and without diabetes. The sizes of the MLBs had a distribution of μm in diameter from microscopic observations of 117 MLBs.33 They corrected the diameters to μm by a factor of to account for the probability that the sections were not made through the maximum cross-sections of the particles. The estimated particle densities were and for the normal-aging transparent lenses and the cataractous lenses, respectively. The refractive index of the lipid shell of the MLBs was estimated to be 1.50 by Matsuzaki et al.34 The thickness of the lipid shell was estimated to range from 15 to 50 nm.33 A representative refractive index of 1.49 as suggested by Gilliland et al. for the cytoplasm inside the MLBs was used.19,33 The refractive index of the GRIN lens model was applied to the surrounding cytoplasm. As the lipid shell and the interior of the MLBs had similar assumed refractive indices, and the shell was as thin as a few tens of nm, the internal refractive index of the MLBs was applied in the simulation. A normal distribution was used for the particle sizes and the diameters of 1.3 and 4.1 μm, twice the standard deviation from the mean, were assigned to be the points of the normal distribution. The equivalent obscuration area fractions were calculated as and for the normal-aging and cataractous lenses, respectively. 3.3.2.Retina fundusVarious fundus reflection models proposed since the 1960’s were reviewed in Berendschot et al.35 The individual anatomical components in ocular fundus exhibited directional reflectance other than perfectly diffuse surfaces.36 However, when the integral reflectance was considered, in vitro measurements of the porcine fundus37 showed that the fundus behaved generally as a Lambertian reflector within 20% deviations. Also, previous studies had adopted the Lambertian assumption to either report the integral fundus reflectance38,39 or to validate the fundus reflection model.40 Accordingly, the fundus of the human retina was considered as a Lambertian diffusing surface in this study. One ray hitting the retina surface will be reflected in random directions. The reflectance values at visual wavelengths were adopted from Zagers et al.26 For instance, the reflectance value at 555 nm is about 0.0135. 3.3.3.CorneaDue to the lack of biometric data for the scattering model in the cornea, the scattering in the cornea was also simulated by adding scattering particles. The model has three volumetric scattering factors, including the particle size distribution, the equivalent obscuration area fraction, and the particle refractive index. After the crystalline lens scattering and retina fundus diffusing model was constructed, these parameters were varied until the veiling luminance of the eye model matched the values calculated from the CIE disability glare general formula. The simulation configuration is shown in Fig. 4, where a glare source at infinity was modeled at different angles departed from the visual axis temporally. The entrance pupil of the eye was set at 4 mm in diameter for typical photopic conditions. The veiling luminance received at the fovea (in ) was normalized with the irradiance at the cornea entrance face (in lux) and compared with CIE general disability-glare formula,27 where is the angle from the visual axis valid in (0.1, 100) degrees, and is a parameter for the ocular pigmentation, ranging from for black eyes to for very light eyes. A value of was used in this study to simulate dark-brown eyes in Asian population. The flux detected at the fovea was divided by the area of the exit pupil and the solid angle subtended by the fovea with respect to the exit pupil. This transformation provides the veiling luminance in this study.4.Results4.1.Monochromatic MTFsThe schematic of the eye model and the corresponding PSF on the retina for an object at infinity with a wavelength of 555 nm are shown in Fig. 5. The light rays travel parallel to the visual axis (5 deg from the optical axis) before entering the eye and are focused on the fovea. Due to the tilting angle of the visual axis and the nasal shift of the pupil, the resulting spot diagram shows apparent rotational asymmetry. Nevertheless, the MTF in red curve shown in Fig. 6 did not exhibit distinct resolutions in the sagittal and tangential directions. The black dotted line shows the diffraction limit, while the dash-dotted and the solid red lines show the sagittal and tangential MTFs of the eye model, respectively. With the scattering model applied in the human eye model, the mean MTF was redrawn in the blue curve. The solid black line shows the fitted curve to the experimental data in vivo in Guirao et al.28 for the age group of 40 to 50 years old with a 4-mm pupil size at the wavelength of 543 nm. It is observed that the eye model without the intraocular scattering model overestimated the MTF compared to the experimental data from double-pass measurements. The blue curve in Fig. 6 was the MTF with the intraocular scattering model. The results associated with the scattering model will be detailed in Sec. 4.3. The blue curve in Fig. 6 showed a nice match to the experimental data when the scattering model was applied in the eye model. 4.2.Polychromatic MTFsThe chromatic dispersion curves of the ocular media modeled by the Cauchy equations [Eq. (3) and Table 3] are shown in Fig. 7. The curves for the aqueous and vitreous humors almost coincide. For the crystalline lens, the highest and lowest refractive indices required for constructing the GRIN model are plotted. The refractive-index curves of the lens along the optical axis at five wavelengths, 450.0, 486.1, 555.0, 587.6, and 656.3 nm, are shown in Fig. 8. The chromatic optical powers obtained from the eye model are listed in Table 4 and plotted in Fig. 9. The values for the human eye in reality were calculated by the best-fit Cauchy equation to experimental data in Atchison and Smith,25 where is the chromatic difference of optical power in Diopters and was set to zero at 590.0 nm. The maximum difference in Table 4 is 0.021 D, which indicates that the model successfully resembles the chromatic dispersion of human eyes. Figure 10 shows the MTF with five equally-weighted wavelengths at 450.0, 486.1, 555.0, 587.6, and 656.3 nm. The resolutions in the sagittal and tangential directions have no significant difference but are lower than the monochromatic MTF (Fig. 6) due to chromatic aberrations.Fig. 9Chromatic difference of the optical powers obtained from the eye model at five wavelengths. The blue line represents the human dispersion curve based on experimental data.  Table 4Chromatic optical powers of the schematic eye at five wavelengths. 4.3.Intraocular Scattering and Veiling LuminanceFigure 11 shows the results of the intraocular scattering model. The horizontal axis indicates the angle between the glare source and the visual axis. The effect of entoptic scattering is demonstrated by the veiling luminance at the retina normalized to the glare illuminance at the cornea entrance face. The red, green, and blue curves are plotted from CIE general disability glare equation for 10, 40, and 70 year-old eyes, respectively. The data points with plus marks are the sampling points of the human eye model with a 40-year-old transparent lens. The parameters of the cornea scattering model were varied to have the data points approaching the CIE general disability glare formula. After an extensive parameter search, the cornea scattering model was tuned to have the refractive index of scattering particles about 1.49, the particle size about 7.0 μm, and an obscuration area of per . These values provide an equivalent cornea scattering model in simulating the CIE general disability glare, but do not necessarily correspond to the realistic scattering particles in cornea. The resulted fitting errors were listed in the form of relative errors in Table 5. The scattering model preformed reasonably well in reproducing the veiling luminance compared to that calculated from the CIE general disability glare formula. Fig. 11Veiling luminance due to intraocular scattering. With the value at 0 and three age parameters, the CIE general disability glare formula is plotted in three curves with red for 10, green for 40, and blue for 70 years-old subjects. The data points with plus marks are samples from the 40-year-old human eye model with a transparent lens. The data points with diamond marks are samples from the 40-year-old human eye model with a cataractous lens.  Table 5The relative error between the CIE general disability glare formula and the constructed human eye model.

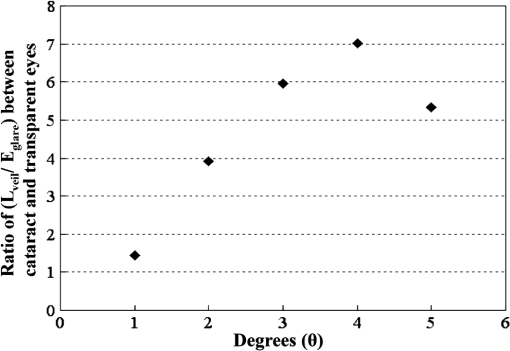

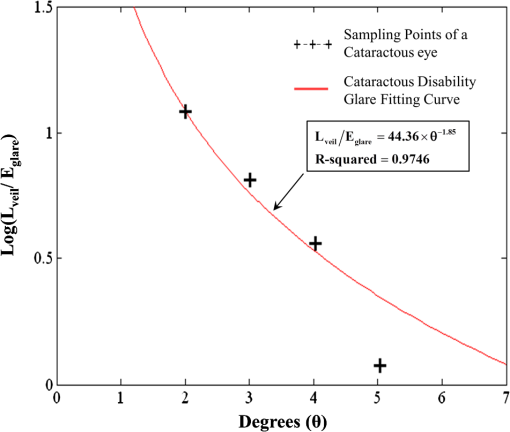

By replacing the transparent lens with a cataractous lens, five sampling points of values corresponding to the glare angles from 1 deg to 5 deg were also plotted in Fig. 11. It is observed that the veiling luminance from a cataractous eye is higher than that from a transparent eye. The ratio of the modeled veiling luminance between the cataractous and the transparent eyes was plotted in Fig. 12. The ratio was about 4 to 7, except for the glare angle of 1 deg. When the glare angle was 1 deg, the flux falling at the detecting fovea area would come from two sources, one from the focal spot of the glare source, and the other from intraocular scattering. Hence the ratio of the veiling luminance between the cataractous and the transparent eyes was altered. The study by de Waard et al.41 showed that intraocular scattering of nuclear cataracts was about 3 to 4 times of intraocular scattering of normal-aging eyes for the glare angle between 5 deg and 20 deg. The ratio obtained from our model is approximately consistent to the numbers obtained by de Waard et al., despite looking at different glare angles. This assumed angular independency of the ratio can be explained by considering the angular inverse-power laws of the veiling luminance of cataractous and transparent eyes. The angular dependence of intraocular straylight in cataractous eyes was found to closely resemble the classic Stiles-Holladay approximation ()42 and hence approximately inversely proportional to the second power of the glare angle.41,43 For comparison, the sampling points for the glare angles of 2 deg to 5 deg from our cataractous lens were curve-fitted to an equation of the inverse-power law. The data from the 1-deg glare angle was excluded as the scattered light detected at the fovea was coupled with the focal spot of the glare source. The resulting fitted curve was with an R-squared value, the coefficient of determination in the regression analysis, of about 0.9746. The multiplication constant in Eq. (8) was larger than the value 10 in the Stiles-Holladay formula, suggesting a 4-time increase of the veiling luminance induced by the cataracts. The value of the exponent was comparable to the value in the Stiles-Holladay formula, and was smaller than the value found by Van den Berg for the angular range of 3.5 deg to 28 deg.43 Nevertheless, the inverse-power characteristic demonstrated a strong angular dependency onintraocular straylight in cataractous eyes. Figure 13 shows the inverse-power fitting result. This formula is specific for the 40-year-old average human eye with a nuclear-sclerosis cataractous lens, clinically graded from 1 to 3 based on a 0 to 4 scale. Formulas for different ages and cataractous opaque percentages could be generated in a similar fashion.5.DiscussionIn our simulation, the scatter contributions from the cornea, lens, and fundus were found approximately independent for the glare angles from 2 deg to 5 deg. That is, we could remove the scattering properties of the lens and fundus, and calculate the flux detected at the fovea to represent the scattering contribution of the cornea. Similar operations can be done for the lens and the fundus. If we added the three individual contributions together, the result was very close to what we could get by having scatters from the three components at the same time. Table 6 provides the individual contributions from the three components in the scattering model. For the glare angle as small as 1 deg, the contributions from the cornea and the lens are coupled together and hence were not listed. Figure 14 illustrates the composition of the veiling luminance. It can be observed that the flux provided by fundus scattering was relatively small when the glare angle was below 5 deg. Also, flux provided by fundus scattering was approximately constant with respect to the glare angle. The contributions from the cornea and lens both exhibit a decaying characteristic with respect to the glare angle. However, the curve for the lens did not decay as fast as the curve of the CIE 1999 standard.27 Hence the curve for the cornea model must decay much faster in order to fit the CIE 1999 standard. When we adjusted the scattering particle size and concentration in the cornea, only one combination of these two parameters would provide the appropriate decay feature. The fitted particle size was about 7.0 μm and the obscuration area was per in the cornea. Table 6Scatter contributions from the cornea, lens, and fundus.

Fig. 14Illustration of the veiling luminance composition in linear-scale axes. The sum of the contributions from the cornea, lens and retina fundus equals the CIE general disability glare curve.  The contributions of the three components in our scattering model have shown some discrepancies to the reported 30-40-20% contributions from cornea-lens-retina in the literature data.16,17 However, previous studies have been measured at angles larger than 10 deg, while smaller angles below 5 deg were considered in the present study. For Mie scattering from particles larger than the incident wavelength, the scattering at small angles behaves differently from that at angles larger than 10 deg. For the purpose of assessing visual performance under the influence of glare sources, the calculation of the target image and the veiling luminance could be separated based on the assumption of a linear imaging system. The proposed three-component model can be utilized as an equivalent model to simulate scattering behavior at small glare angles, where the experimental data is currently absent. The image formation can be accomplished by the geometric optical eye model, while the scattering model has enabled us to have a modulation transfer function matching the in vivo measurements as in Fig. 6. The influence of the glare source at large glare angles can be calculated directly by the CIE general disability glare formula and superimposed to the image. This process is much easier for larger glare angles, where the consideration of the realistic ocular scatterers is not necessary for the calculation of the veiling luminance. As the proposed model matching the CIE 1999 standard at glare angles below 5 deg, the parameters used for the scattering particles in the cornea did not correspond to the wavelength dependency of cornea scattering reported in previous studies.44,45 The in vitro study on rabbit corneas44 and in vivo study on human corneas45 both suggested a strong wavelength dependency of the inverse 4th power, which corresponds to the Rayleigh scattering by particle sizes much smaller than the wavelength of the incident light. On the contrary, the fitted particle diameter of 7.0 μm in our cornea model corresponds to strong forward scattering by the Mie theory. This inconsistency suggested that the combined effect of the cornea and fundus scattering only represent an equivalent model. Although the integral reflectance of the porcine fundus exhibited the Lambertian characteristic37 and the Lambertian assumption has been adopted in previous studies,38–40 the internal scattering from the multilayer fundus to the retina and directly absorbed at the fovea photoreceptors was not considered. Due to the lack of the experimental data on the angular distribution of internal fundus scattering, the Lambertian characteristic was used in the present model. As shown in Fig. 14, the combined effect of the cornea and fundus must provide a strong decaying behavior with respective to the glare angle. By adopting the Lambertian assumption at the fundus, the angular dependency was compensated by the cornea to yield an equivalent model. In order to have a cornea model corresponding to the in vivo Rayleigh scattering characteristic, it would be sensible to hypothesize internal fundus scattering at very shallow angles towards the retina. This will raise the angular dependency as well as the contribution of the fundus scattering to the veiling luminance. Computations by existing fundus refection models such as those mentioned in Berendschot et al.35 or direct measurements would be beneficial to provide the necessary angular distribution of the internal fundus scattering. In addition, in vitro light scattering measurements from donor lenses by van den Berg43,46 at angles from 10 deg to 165 deg suggested wavelength dependency of the lens scattering. Two candidate groups of particles were proposed,46 including a small mean particle size of about 20-nm diameter with a 0.023 volume fraction and a larger mean particle size of about 1.4-μm diameter with a volume fraction. The corresponding scattering would be a mixture of the Rayleigh and Rayleigh-Gans-Debye types and have strong wavelength dependency. As the current study focuses on the disability glare at angles smaller than 5 deg, it is the forward scattering by particles larger than the incident wavelength that play an important role. Hence the contribution of the Rayleigh scattering from particles as small as 20-nm diameter is negligible. For the model to extend into much larger glare angles, Rayleigh scattering by small particles must be taken into account. As discussed earlier, the veiling luminance contributed from larger glare angles can be readily calculated by the CIE 1999 standard. By having a scattering model matching the CIE 1999 standard for the angular range of 1 deg to 5 deg, the current model yields a modulation transfer function matching the in vivo measurements and provides a simulation tool for visual performance assessment. 6.ConclusionAbundant ocular biometric data, advances in optical simulation software, and accurate prior models in the literature have enabled us to construct a schematic human eye model that resembles physiological eyes with the functions of age and lens accommodation. The visual acuity and chromatic dispersion of the schematic eye model matched the behavior of real human eyes. The effect of the scattering model in an average eye with a transparent crystalline lens was also confirmed by the CIE disability glare general formula. The disability glare curve of cataract eyes was predicted by replacing the transparent lens with a cataractous lens. A cataractous disability glare formula was then generated by curve-fitting. The comparison between transparent eyes and cataract eyes shows that cataract eyes are more sensitive to glare sources, especially at a glare angle of 2 deg to 4 deg. This model is anticipated to become a powerful tool for studying visual performance with various combinations of different objects, light sources and observers with normal or altered conditions. AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported in part by the National Central University’s Plan to Develop First-class Universities and Top-level Research Centers Grants 995939 and 100G-903-2, and the National Science Council Grant NSC-100-3113-E-008-001. ReferencesH. von Helmholtz, Physiologische Optik, 152 3rd ed.Voss, Hamburg

(1909). Google Scholar

A. Gullstrand, Physiologische Optik, 299 3rd ed.Voss, Hamburg

(1909). Google Scholar

H. H. Emsley, Visual Optics, 1 360 5th ed.Hatton Press Ltd., London

(1952). Google Scholar

Y. Le Grand, Optique Physiologique I, 52 Ed. Rev. Opt., Paris

(1953). Google Scholar

W. Lotmar,

“Theoretical eye model with aspherics,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am., 61

(11), 1522

–1529

(1971). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSA.61.001522 JOSAAH 0030-3941 Google Scholar

R. NavarroJ. SantamaríaJ. Bescós,

“Accommodation-dependent model of the human eye with aspherics,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 2

(8), 1273

–1280

(1985). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.2.001273 JOAOD6 0740-3232 Google Scholar

A. Popiolek-Masajada,

“Numerical study of the influence of the shell structure of the crystalline lens on the refractive properties of the human eye,”

Ophthalmic Physiol. Opt., 19

(1), 41

–48

(1999). http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1475-1313.1998.00403.x 0275-5408 Google Scholar

J. W. Blaker,

“Toward an adaptive model of the human eye,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am., 70

(2), 220

–223

(1980). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSA.70.000220 JOSAAH 0030-3941 Google Scholar

H. L. LiouN. A. Brennan,

“Anatomically accurate finite model eye for optical modeling,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 14

(8), 1684

–1695

(1997). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.14.001684 JOAOD6 0740-3232 Google Scholar

A. V. GoncharovC. Dainty,

“Wide-field schematic eye model with gradient-index lens,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 24

(8), 2157

–2174

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.24.002157 JOAOD6 0740-3232 Google Scholar

I. Escudero-SanzR. Navarro,

“Off-axis aberrations of a wide-angle schematic eye model,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 16

(8), 1881

–1891

(1999). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.16.001881 JOAOD6 0740-3232 Google Scholar

L. N. Thiboset al.,

“The chromatic eye: a new reduced-eye model of ocular chromatic aberration in humans,”

Appl. Opt., 31

(19), 3594

–3600

(1992). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.31.003594 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

R. NavarroF. PalosL. González,

“Adaptive model of the gradient index of the human lens. I. Formulation and model of aging ex vivo lenses,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 24

(8), 2175

–2185

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.24.002175 JOAOD6 0740-3232 Google Scholar

R. NavarroF. PalosL. M. González,

“Adaptive model of the gradient index of the human lens. II. optics of the accommodating aging lens,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 24

(9), 2911

–2920

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.24.002911 JOAOD6 0740-3232 Google Scholar

J. E. Purkinje,

in Beobachtungen und Versuche zur Physiologie der Sinne,

63

–69

(1823). Google Scholar

J. J. VosJ. Boogaard,

“Contribution of the cornea to entoptic scatter,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am., 53

(7), 869

–873

(1963). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSA.53.000869 JOSAAH 0030-3941 Google Scholar

J. J. VosM. A. Bouman,

“Contribution of the retina to entoptic scatter,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am., 54

(1), 95

–100

(1964). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSA.54.000095 JOSAAH 0030-3941 Google Scholar

T. J. T.P. van den BergJ. K. IjspeertP. W. T. de Waard,

“Dependence of intraocular straylight on pigmentation and light transmission through the ocular wall,”

Vision Res., 31

(7–8), 1361

–1367

(1991). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(91)90057-C VISRAM 0042-6989 Google Scholar

K. O. Gillilandet al.,

“Distribution, spherical structure and predicted Mie scattering of multi-lamellar bodies in human age-related nuclear cataracts,”

Exp. Eye Res., 79

(4), 563

–576

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.exer.2004.05.017 EXERA6 0014-4835 Google Scholar

C. C. Sunet al.,

“Analysis of the far-field region of LEDs,”

Opt. Express, 17

(16), 13918

–13927

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.17.013918 OPEXFF 1094-4087 Google Scholar

C. C. SunS. Y. TsaiT. X. Lee,

“Enhancement of angular flux utilization based on implanted micro pyramid array and lens encapsulation in GaN LEDs,”

J. Display Technol., 7

(5), 289

–294

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JDT.2011.2107881 IJDTAL 1551-319X Google Scholar

C. C. Sunet al.,

“Light extraction enhancement of GaN-based LEDs through passive/active photon recycling,”

Opt. Commun., 284

(20), 4862

–4868

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2011.06.051 OPCOB8 0030-4018 Google Scholar

R. Navarro,

“Incorporation of intraocular scattering in schematic eye models,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am., A2

(11), 1891

–1894

(1985). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.2.001891 JOSAAH 0030-3941 Google Scholar

M. DubbelmanG. L. Van der HeijdeH. A. Weeber,

“Change in shape of the aging human crystalline lens with accommodation,”

Vision Res., 45

(1), 117

–132

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2004.07.032 VISRAM 0042-6989 Google Scholar

D. A. AtchisonG. Smith,

“Chromatic dispersions of the ocular media of human eyes,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 22

(1), 29

–37

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.22.000029 JOAOD6 0740-3232 Google Scholar

N. P. A. Zagerset al.,

“Simultaneous measurement of foveal spectral reflectance and cone-photoreceptor directionality,”

Appl. Opt., 41

(22), 4686

–4696

(2002). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.41.004686 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

J. J. VosT. J. T. P. van den Berg,

“Report on disability glare,”

CIE collection, 135

(1), 1

–9

(1999). Google Scholar

A. Guiraoet al.,

“Average optical performance of the human eye as a function of age in a normal population,”

Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., 40

(1), 203

–213

(1999). http://www.iovs.org/content/40/1/203.abstract IOVSDA 0146-0404 Google Scholar

A. G. BennettR. B. Rabbetts, Clinical Visual Optics, 17

–18 2nd ed.Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford

(1989). Google Scholar

G. Westheimer,

“Image quality in the human eye,”

J. Mod. Opt., 17

(9), 641

–658

(1970). http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/713818355 JMOPEW 0950-0340 Google Scholar

C. E. Joneset al.,

“Refractive index distribution and optical properties of the isolated human lens measured using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),”

Vision Res., 45

(18), 2352

–2366

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2005.03.008 VISRAM 0042-6989 Google Scholar

K. O. Gillilandet al.,

“Multilamellar bodies as potential scattering particles in human age-related nuclear cataracts,”

Mol. Vis., 7 120

–130

(2001). http://www.molvis.org/molvis/v7/a18/ MVEPFB 1090-0535 Google Scholar

M. J. Costelloet al.,

“Predicted light scattering from particles observed in human age-related nuclear cataracts using Mie scattering theory,”

Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., 48

(1), 303

–312

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1167/iovs.06-0480 IOVSDA 0146-0404 Google Scholar

K. Matsuzakiet al.,

“Optical characterization of liposomes by right angle light scattering and turbidity measurement,”

Biochim. Biophys. Acta, 1467

(1), 219

–226

(2000). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0005-2736(00)00223-6 BBACAQ 0006-3002 Google Scholar

T. T. J. M. BerendschotP. J. DeLintD. van Norren,

“Fundus reflectance - historical and present ideas,”

Prog. Retinal Eye Res., 22

(2), 171

–200

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1350-9462(02)00060-5 PRTRES 1350-9462 Google Scholar

R. W. Knighton,

“Quantitative reflectometry of the ocular fundus,”

IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag., 14

(1), 43

–51

(1995). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/51.340747 IEMBDE 0739-5175 Google Scholar

D. A. Salyeret al.,

“In vitro multispectral diffuse reflectance measurements of the porcine fundus,”

Invest. Ophthalmol. Visual Sci., 46

(6), 2120

–2124

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1167/iovs.04-1020 IOVSDA 0146-0404 Google Scholar

F. C. DeloriK. P. Pflibsen,

“Spectral reflectance of the human ocular fundus,”

Appl. Opt., 28

(6), 1061

–1077

(1989). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.28.001061 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

J. van de KraatsT. T. J. M. BerendschotD. van Norren,

“The pathways of light measured in fundus reflectometry,”

Vision Res., 36

(15), 2229

–2247

(1996). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(96)00001-6 VISRAM 0042-6989 Google Scholar

M. HammerD. Schweitzer,

“Quantitative reflection spectroscopy at the human ocular fundus,”

Phys. Med. Biol., 47

(2), 179

–197

(2002). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/47/2/301 PHMBA7 0031-9155 Google Scholar

P. W. T. de Waardet al.,

“Intraocular light scattering in age-related cataracts,”

Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., 33

(3), 618

–625

(1992). http://www.iovs.org/content/33/3/618.abstract IOVSDA 0146-0404 Google Scholar

J. J. Vos,

“Disability glare - a state of the art report,”

CIE J., 3 39

–53

(1984). Google Scholar

T. J. T. P. van den Berg,

“Depth-dependent forward light scattering by donor lenses,”

Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., 37

(6), 1157

–1166

(1996). http://www.iovs.org/content/37/6/1157.abstract IOVSDA 0146-0404 Google Scholar

T. Feuk,

“The wavelength dependence of scattered light intensity in rabbit corneas,”

IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., 18

(2), 92

–96

(1971). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TBME.1971.4502808 IEBEAX 0018-9294 Google Scholar

T. J. T. P van den BergK. E. Tan,

“Light transmittance of the human cornea from 320 to 700 nm for different ages,”

Vision Res., 34

(11), 1453

–1456

(1994). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0042-6989(94)90146-5 VISRAM 0042-6989 Google Scholar

T. J. T. P. van den Berg,

“Light scattering by donor lenses as a function of depth and wavelength,”

Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci., 38

(7), 1321

–1332

(1997). http://www.iovs.org/content/38/7/1321.abstract IOVSDA 0146-0404 Google Scholar

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||