|

|

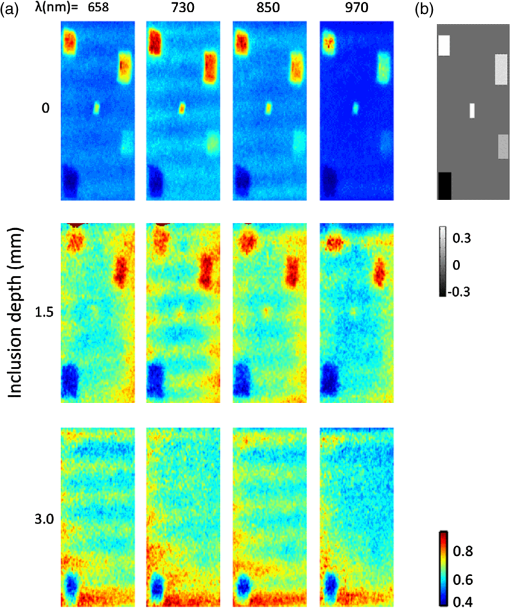

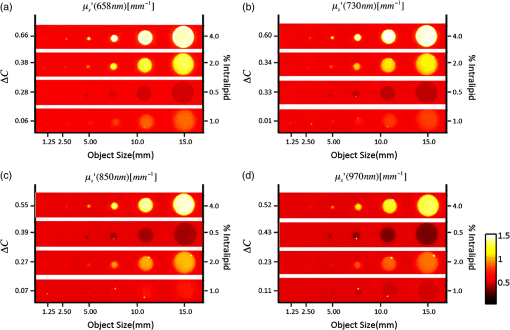

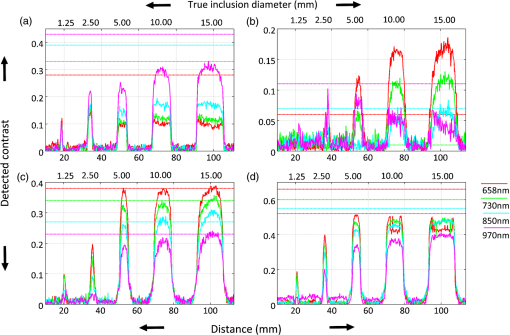

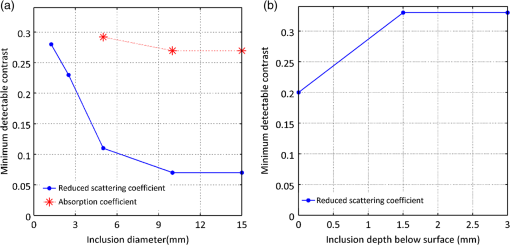

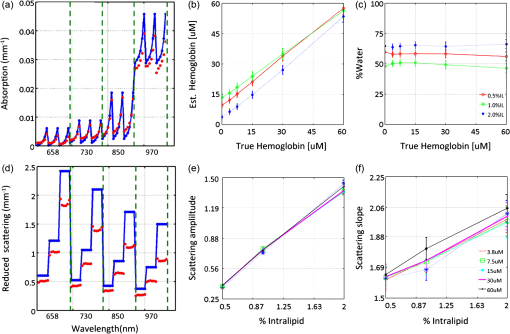

1.IntroductionThe feasibility of spatial frequency domain imaging (SFDI) for breast surgical margin assessment was evaluated using tissue-simulating phantoms to measure quantitative accuracy and contrast-detail resolution, and fully intact surgical specimens to assess the clinical application of this acquisition geometry to surgical breast tissues. SFDI projects sinusoidal patterns of near-infrared (NIR) light onto biological tissues to quantify wide-field spectral absorption and scattering. This unique planar imaging modality was pioneered by investigators at the University of California at Irvine and commercialized by Modulated Imaging Inc. for biological imaging at a spatial resolution between coherent and diffuse optical imaging.1 The frequency dependence of the modulation amplitude provides a sensitive measurement to uniquely separate optical effects using analytical models of light transport; where high spatial frequencies are sensitive to short pathlength phenomenon, primarily scattering by local fluctuations in tissue morphology, and continuous illumination is sensitive to both absorption and scattering.1 No exogenous probes were necessary for microscopic specificity, but high spatial frequencies were probed (up to ) to improve sensitivity to scattering by tissue ultra-structure. The spatial frequency of the illumination pattern integrated optical parameterization with volume averaging in depth and improved signal localization—optical parameters were recovered at depths approximately 1 to 8 mm,2 a range appropriate for surgical margin assessment. The scattering spectrum can be exquisitely sensitive to morphological transformations perceived by pathologists when the confounding effects of multiple light scattering are minimized; this is typically achieved through local sampling of reflectance and/or polarization techniques.3–5 Near-source sampling of reflectance by fiber-mediated probes has demonstrated specific correlation with paraffin histology, the diagnostic gold standard, and improved tissue-type discrimination because of sensitivity to the scattering phase function.6–9 Optical coherence tomography10 and confocal sampling geometries11,12 have also been applied for intra-operative diagnoses, but are limited in depth resolution by a multiple scattering background and in field of view (FOV) size (the microscopic FOV is often too small to wholly analyze lumpectomy tissues in a clinically useful timeframe). Diffuse optical tomography can be useful to quantify bulk transformations in tissue physiology over several centimeters,13–15 but the spatial resolution corresponds to the scattering coefficient of the tissue16 and this can be insufficient to resolve local transformations by important scattering structures (which mainly have dimensions comparable to the optical wavelength).17 As an intermediate between coherent and diffuse optical techniques, the ability of SFDI to effectively combine wide-field optical imaging with localized scattering contrast is tested. Scattering contrast-detail and contrast-depth resolution were explored in homogeneous polymer and gelatin phantoms with embedded inclusions because recent results suggest spectroscopic scattering features exhibited less variance within pathology subtypes and was ranked as most significant to tissue-type discrimination by an iterative feature ranking algorithm in a pilot clinical study. Quantitative accuracy of the diffusion approximation and scaled-Monte Carlo models of light transport were then compared in tissue simulating phantoms with expected optical properties and finally, goodness of fit was evaluated in reflectance measures acquired from 47 lumpectomy tissues to evaluate application of these models to surgical breast tissues. The diffusion approximation is valid for highly scattering media and for large source-to-detector separations, where high photon scattering renders their transport deterministic. Transport is governed by the reduced scattering coefficient and the absorption coefficient; consequently, information pertaining to the specific phase function is lost18 and scattering can be convolved with absorption effects if reflectance is not measured at multiple source-to-detector separations, or equivalently, at multiple spatial frequencies. Spatially resolved, analytical solutions to the steady state diffusion approximation have been derived by Farrell and Dognitz in the real and spatial-frequency domains, respectively.19,20 These models have demonstrated utility when tailored to specific sampling geometries21,22 and have been improved by higher order approximations to the phase function.23 The diffusion approximation was compared to a forward model based on scaled-Monte Carlo simulations of light transport for sampling at high spatial frequency because direct Monte Carlo simulations were computationally too expensive for an iterative optimization.1 Numerical models were generated by rescaling a single Monte Carlo simulation to extract a wide range of optical properties from spatial-frequency dependent measures, as first realized by Graaff et al.24 and Kienle et al.25 The feasibility of SFDI to distinguish malignant transformations immediately ex vivo in the surgical environment, prior to routine pathological processing, was evaluated in four fully intact, lumpectomy tissues in order to eventually reduce the high rate of secondary excision associated with breast conserving therapy (BCT).26 BCT, which includes local tumor excision followed by moderate dose-radiation therapy, was the treatment of choice for nearly 75% of the approximately 300,000 new breast cancer patients diagnosed in 2011.27 Its survival rates are equivalent to those of mastectomy when surgical resection margins are negative for residual cancer,28,29 but margins positive for residual cancer have been associated with an increased risk of local recurrence30–32 and mortality.33 Margin assessment is routinely performed post-operatively by paraffin histology because frozen section analysis is limited by freezing artifacts in adipose tissues.34,35 At Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC), colored inks are superficially applied to the resected tissue to define margins for post-operative assessment and surgical margins are re-excised if invasive tumor is detected at the margin or if ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is detected less than 2 mm from the inked surface.36 Tissues excised during breast conserving surgery (BCS) may include tumors up to 5 cm in diameter, surrounded by a targeted layer of grossly normal tissue that is nearly 1 cm thick. Ideally, SFDI might be used to assess the full tumor specimen in a noncontact manner, while maintaining sensitivity to malignant transformations in localized volumes. 2.Methods2.1.Spatial Frequency Domain Imaging SystemA compact SFDI system, purchased from Modulating Imaging Inc., was used to quantitatively image optical parameters at four NIR wavelengths (658, 730, 850, and 970 nm) using spatially varying light. In series, 30 spatial frequencies uniformly distributed from up to were projected per wavelength onto each sample using high power light-emitting diodes (LEDs), a projection system and a digital micro-mirror device. Total data acquisition (DAQ) time was 10 min on average. Structured light patterns were generated using C# code and an ALP applications program interface, MI Acquire (v1.3.12), provided by Modulated Imaging Inc. (Irvine, California). A 12-bit CCD-based camera, coregistered with the projector, captured narrow bands of spectral reflectance using interference filters. Illuminating at a small angle to normal incidence and cross-linear polarizers placed at the source and detector minimized specular reflections. Figure 1 shows the fully integrated projection and camera subsystems mounted on a -axis post.1,37 2.2.Data Acquisition and CalibrationA planar and harmonically varying source illuminated each sample in reflectance geometry at normal incidence according to Here, represents the decay of the source as a function of depth in the media, represents its phase offset, and describes the spatial frequency of modulation in the -direction. Assuming a linear medium and symmetry considerations, each sinusoidal source gave rise to a reflected intensity () with the same frequency and phase:1 A three-phase demodulation was then employed to extract the frequency dependent modulation amplitude, , from the reflected intensity and to remove ambient noise common to all three images:38 The modulation amplitude of a siloxane titanium dioxide () reflectance standard with expected optical properties, , was measured at each imaging session for phantom-based calibration and to correct for spatial nonuniformity in the illumination and imaging systems. The reference standard was characterized by diffuse optical spectroscopy (DOS), which combines frequency domain photon migration with broadband spectroscopy.39 Diffuse reflectance of the standard () was predicted from its expected optical properties using a forward model of light transport. Absolute reflectance of the sample () was subsequently calculated according to Each spatial sampling point was calibrated and analyzed separately. 2.3.Comparison of Analytical Models of ReflectanceOptical parameters were fit by minimizing the residual sum of squares between the measured modulation amplitude and its analytical solution in a semi-infinite, turbid medium, modeled according to diffusion16 and scaled-Monte Carlo simulations of light transport.25 The former approximation assumes isotropic scattering and the latter, a Henyey-Greenstein phase function.1 Rescaling a single, spatially and temporally resolved Monte Carlo simulation significantly reduced the computational burden associated with iterative estimation of optical parameters. However, computing its Fourier transformation was still time intensive in a minimization scheme. Consequently, scaled-Monte Carlo simulations of the modulation amplitude were stored in a 30-frequency, 4-wavelength, look up table (LUT) to reduce the computational burden associated with iterative estimation of spectral parameters. The LUT modulation amplitude was computed for absorption coefficients varying from 0 to in steps of and scattering coefficients varying from 0.2495 to in steps of . A LUT was not implemented for the diffusion approximation because computation of its forward analytical solution was direct; however, other groups have implemented this to improve speed of optical parameter rendering.1 Cuccia et al. compared the accuracy of the diffusion approximation and scaled-Monte Carlo simulation of light transport using computer simulations for a range of optical pathlengths, and showed that for low spatial frequencies in a medium with an albedo approaching 1, the diffusion error remains less than 16%.1 Here, model-data goodness of fit was evaluated in modulated reflectance measurements acquired from 47 patients in a HIPAA-compliant, prospective study, approved by Institutional Review Board for the protection of human subjects common to evaluate the applicability of these models to light scattering in surgical breast tissues. The adjusted coefficient of determination was used to quantify data variance explained by the model and the lowest adjusted Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to rank model performance because it is based on the negative log likelihood of the residuals and consequently, provided a relative assessment of nonlinear model fit (the coefficient of determination is known to inadequately assess nonlinear regression because the total sum of squares is not equal to the regression sum of squares, as in the linear case).40,41 A spectrally constrained optimization was explored with the diffusion approximation given a priori knowledge of the chromophore extinction spectra and the wavelength-dependence of the reduced scattering coefficient. However, an unconstrained optimization was observed to be more robust given the limited number of wavelengths sampled. The ability of recovered spectral parameters to distinguish breast tissue types in this large tissue population are evaluated elsewhere; here the optimization of model-data fit is presented. 2.4.Optical Parameter RecoverySpectral parameters were subsequently fit according to absorption by the endogenous tissue chromophores, oxygenated-hemoglobin (), deoxygenated-hemoglobin (Hb), and water, and the wavelength-dependence of light scattering. Concentrations of and Hb were recast as total hemoglobin () and percent oxygen (). A power law dependence on wavelength was used to describe the Mie scattering spectrum: the scattering amplitude (A) and scattering power (b) were calculated relative to the reduced scattering coefficient of 1% intralipid at 42 Adipose was not included in the basis set of fit chromophore extinction spectra because the four wavelengths sampled were insufficient to uniquely separate water and lipid absorption; an assumption about lipid absorption was necessary during optimization to prevent saturation of percent lipid or percent water at its bounds, as previously discussed by Mazhar.43 Suspected lesions were primarily fibroglandular and pathology-assessed lesions were on average, 3% adipose, as determined prospectively by immunohistochemistry. 2.5.Tissue Simulating PhantomsA homogeneous, polymer-based phantom with inclusion wells varying in diameter (1.25 to 15 mm) was custom designed and constructed by INO Inc. (Biomimics phantom, Quebec City, Quebec, California) for contrast-detail analysis. The absorption and reduced scattering coefficients of the phantom at 800 nm were 0.008 and , respectively; the refractive index was 1.52 and carbon black was used as an absorber. The inclusions were filled with dilutions of Intralipid, as shown in Fig. 2, to determine the minimum size of detectable scattering contrast in reduced scattering maps. Actual scattering contrast varied from 1% to 66% and was compared to measured scattering contrast; plotted along the center -axis of each phantom according to: where is the signal from the inclusion and is the signal from the background. Sensitivity to scattering contrast at depth was additionally investigated using a gelatin phantom with scattering heterogeneities embedded 0 to 3 mm in a homogenous background, constructed with Intralipid and Nigrosin dye. Gelatin was boiled, cooled to 40°C (warm to the touch, but not solidified), and diluted with 10% Intralipid to the expected reduced scattering coefficient.44 Inclusions were carved in the gelatin once it had cooled and were filled with another batch of liquid gelatin with greater or lower Intralipid concentration, as described by Pogue and Patterson.45Fig. 2Contrast-detail curves for scattering heterogeneities that vary in size (-axis) and contrast (-axis); measured at (a) 658 nm, (b) 730 nm, (c) 850 nm, and (d) 970 nm.  A series of homogenous liquid phantoms with expected optical properties were imaged to test the absolute quantification of absorption and reduced scattering coefficients by SFDI. Phantoms were constructed from Intralipid-20% (Fresenius Kabi, Uppsala, Sweden), a fat emulsion used to mimic scattering in biological tissues, diluted with phosphate buffered solution (PBS) and porcine blood.42 PBS was used to dilute the blood to maintain blood cells at their physiological pH of 7.4. Scattering concentrations varied from 0.5% to 2.0% and the reduced scattering coefficient of each dilution was computed per wavelength according to Michels et al.42 Initial dilutions of porcine blood were prepared using measured hematocrit values assayed with a HemoCue© meter (Hb 201 system, HemoCue Inc., Cypress, California) for each sample, and the final solution values were serially diluted from 60 to 3.75 µM, the expected physiological range in breast tissue.46 Expected optical properties were subsequently calculated using the forward model of light transport and assuming the chromophore extinction spectra.44 The Pearson’s correlation coefficient, and coefficient of variation for all expected and recovered optical parameters were computed for model comparison. The coefficient of variation is just the standard deviation normalized to the distribution mean, and approaches 1 when two variables change together exponentially. 2.6.Spatial Frequency Domain Imaging of LumpectomiesFour fully intact and un-inked lumpectomy specimens were imaged immediately upon excision at the time of primary surgery to test the clinical translation of this new technology. The surgeon participated in each imaging session and placed sutures in the excised tissues to safeguard knowledge of its orientation until surgical inks were applied and the tissue was sent to pathology. Fifteen spatial frequencies uniformly distributed between 0 and were projected per wavelength onto each margin in under 2 min and spectral parameters were reconstructed using the scaled-Monte Carlo LUT. Tissues were extremely malleable, so only one to three margins were imaged per specimen. 3.Results3.1.Contrast-Detail AnalysisMaps of the reduced scattering coefficient are shown in Fig. 2 for the contrast-detail phantoms and contrast line scans are plotted in Fig. 3(a) through 3(d). Detectable scattering contrast decayed asymptotically with inclusion size, as shown in Fig. 4(a): a 1.25 mm diameter inclusion was detectable when scattering contrast was at least 28%; the lowest detectable scattering contrast was 7% when the inclusion diameter was at least 10 mm. Recovered scattering contrast was observed to be lower than the expected scattering contrast, indicated by the dashed lines in Fig. 3(a) through 3(d), likely due to assumptions made about the optical properties of the inclusions. Figure 4(a) shows that absorption contrast, due to variations in phantom water content, was not detectable for inclusions less than 5 mm in diameter and absorption maps were characterized by a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Figure 5(a) shows the reduced scattering coefficient maps for three phantoms with scattering inclusions placed at depths of 0 to 3 mm. True scattering contrast is mapped in Fig. 5(b); at least 33% scattering contrast was detectable at a 1.5 mm depth. The minimum detectable scattering contrast as a function of inclusion depth is plotted in Fig. 4(b) for the gelatin phantom; similar levels of detectable scattering contrast were observed in the polymer-based phantom. No absorption contrast was introduced into the gelatin phantom and absorption maps showed low signal to noise ratio (SNR) and minimal cross talk with scattering signatures, particularly with increasing inclusion depth. Fig. 3(a)–(d) Detected contrast in reduced scattering maps for each contrast detail phantom per wavelength (indicated by color); scattering contrast is plotted along the center -axis of each phantom. Expected scattering contrast per wavelength indicated by dashed line.  Fig. 4(a) Minimum detectable scattering contrast plotted as a function of inclusion diameter for the reduced scattering coefficient and absorption coefficient. (b) Minimum detectable scattering contrast plotted as a function of inclusion depth for the reduced scattering coefficient. Absorption contrast was not detectable for inclusion diameters less than 5 mm in these phantoms.  3.2.Absolute Quantification of Optical ParametersRecovered and expected optical parameters for Intralipid phantoms, serially diluted with porcine blood and extracted from the scaled-Monte Carlo LUT, are plotted in Fig. 6(a) and 6(d). The reduced scattering coefficient was systematically underestimated (on average, by 26%), but relative trends in the spectral scattering amplitude and slope were conserved. Systematic error in the absolute quantification of scattering was likely influence by the assumed optical parameters of the calibration phantoms, which for Intralipid, was derived by Michels42 using Mie theory and a different acquisition geometry. Spectral parameters extracted from the NIR optical coefficients are plotted as a function of Intralipid and hemoglobin concentration in Fig. 6(b) and 6(c) as well as in 6(e) and 6(f). Recovered hemoglobin values demonstrated insensitivity to scattering variations except at low concentrations and were within of their expected values. The absorption coefficient was overestimated at visible wavelengths for low hemoglobin concentrations () because of the shorter pathlengths sampled. Water quantification was independent of hemoglobin changes and oxygenation levels approached 100% for all liquid phantoms (data not shown). Systematic under-estimation of absorption parameters at 970 nm was observed, likely due to the assumptions about the expected water absorption in the phantoms. Errors in Fourier Sampling theory may have also contributed minimally to amplitude underestimation, and consequently absorption overestimation, at low spatial frequencies.1 The scattering coefficient demonstrated insensitivity to hemoglobin variations, except at the measured concentration limits (0 and 60 μM). The scattering amplitude increased linearly with scattering concentration (low coefficient of variation with Intralipid concentration: 0.26), but the scattering slope depended on both the particle size and number density (high coefficient of variation with Intralipid concentration: 1.36). All recovered absorption and scattering parameters showed strong correlation with their expected values (). Fig. 6(a) and (d) True (blue) and recovered (red) absorption and reduced scattering coefficients extracted from homogeneous, tissue simulating phantoms using scaled-MC simulations as a forward model. Intralipid concentrations varied from 0.5% 1.0% and 2.0%. Hemoglobin concentrations varied from 0 to 60 uM in six serial dilutions. Parameters recovered at all four wavelengths are shown in sequence. (b) and –(c) Spectral absorption parameters mapped as a function of hemoglobin concentration at three scattering concentrations (indicated by line color). (e) and (f) Spectral scattering parameters mapped as a function of Intralipid concentration for six hemoglobin concentrations (indicated by line color). Error bars indicate the standard deviation observed per pixel window.  3.3.Forward Model SelectionTable 1 compares the diffusion approximation and scaled-Monte Carlo simulations of light transport according to model-data goodness of fit in a large cohort of surgical breast tissues. Three variations of the diffusion approximation were explored: a spectrally unconstrained model (a) and two spectrally constrained models (b) and (c), whose optimized parameters are listed in Table 4.2, to investigate the dependence of GOF on spectral constraints. The reduced scattering and absorption coefficients were constrained, respectively, to a power law dependence on wavelength and exponential extinction according to tabulated chromophores. Model (c) implements the most severe spectral constraints by linking the total concentration of hemoglobin to oxygen saturation (bounded between 0% and 100%) during optimization. GOF decreased with increasing spectral constraints, likely due to sparse spectral sampling. The coefficient of determination shows that the spectrally unconstrained diffusion model and scaled-Monte Carlo model performed comparably with regards to model-data goodness of fit, however the lowest adjusted-AIC suggests that the scaled-Monte Carlo model best minimized information loss in this population of surgical tissues. The correlation between the recovered and expected absorption and reduced scattering coefficients was greater than 0.97 for all models; however their coefficient of variation (CV) indicated some exponential trends in absorption estimates with absorber concentration for both the diffusion () and scaled-Monte Carlo models (); likely because the high spatial frequencies probed are less sensitive to the longer photon pathlengths associated with absorption. Sparse spectral sampling may have also limited the accuracy of chromophore quantification. Recovered scattering coefficients varied linearly with their expected values for both models ( to 0.28). The scaled-Monte Carlo model was selected because its recovered absorption parameters varied more linearly with hemoglobin concentration in liquid phantoms within a physiologic hemoglobin range. Table 1Goodness of fit evaluated in breast tissue for three variations of the diffusion approximation and a scaled-Monte Carlo forward model, according to their average adjusted R2 coefficient and the adjusted Akaike information criterion (AIC).

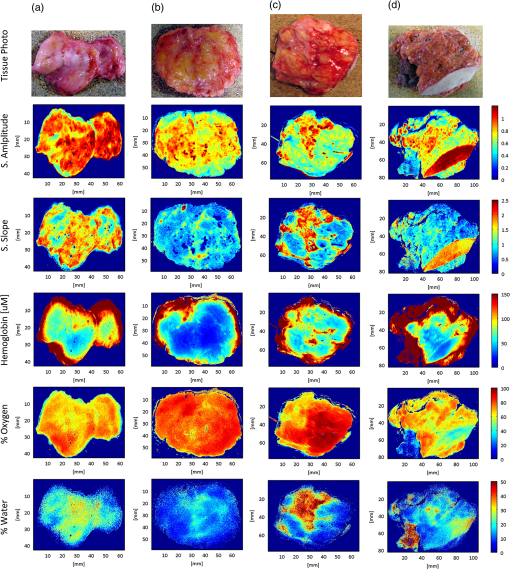

3.4.Challenges Associated with the Clinical Translation of SFDISpectroscopic images of four surgical margins are shown in Fig. 7: column A shows two wire-localized fibroadenomas (0.7 to 0.8 mm in diameter) in a fibrocystic background and column B shows four small fibroadenomas (0.2 to 0.5 cm in diameter) in an otherwise complete pathologic response to neoadjuvent chemotherapy. Column C shows a nearly complete pathologic response to chemotherapy, except one remaining high-grade tumor focus (0.2 cm) in the fibrocystic background. The lymphadenectomy associated with this partial responder is shown in column D; 11 out of 15 lymph nodes were positive for cancer. Oxygenation was the most apparent gauge of tumor response to therapy in these four lumpectomy specimens; oxygen levels in the lymph nodes filled with tumor were lower than those observed in pathologically responsive tumors and fibroadenomas. Variation in optical parameters with time delay after excision reported by Bydlon suggest that oxygen saturation levels of hemoglobin vary nonlinearly within 30 min of resection; whereas, the reduced scattering coefficient and total hemoglobin concentration showed little change over time.47 Consequently, oxygenation could be a valuable diagnostic parameter if imaged in the surgical cavity or immediately at the time of resection. High spectroscopic scattering was observed from fibrocystic tissues (columns A and C) and a lower scattering slope distinguished two large fibroadenomas within a fibrocystic background, as shown in column A. Water content was elevated and oxygenation levels were lower in the upper left quadrant of the partial responder (column C), suggesting that this quadrant was the site of the high-grade tumor focus. The primary challenges observed with the clinical translation of SFDI were edge artifacts, which presented as elevated absorption at the tissue edge, a typical location of tissue profile decline, and orienting spectroscopic images with pathology to validate margin status. Fig. 7Photograph and spectral parameter maps sampled from four lumpectomy margins: (a) fibroadenomas () with diameters of 0.7 to 0.8 mm surrounded by fibrocystic disease, (b) complete pathologic response to neoadjuvent chemotherapy and two small fibroadenomas (diameters of 0.2 to 0.5 mm); (c) partial response to neoadjuvent chemotherapy with residual high grade tumor focus (0.2 mm) and fibrocystic disease; (d) lymphadenectomy associated with case (c). Cancer is present in 11/15 nodes. Skin and muscle in the image field appear white and deep red, respectively in the tissue photograph.  4.DiscussionIn this paper, we investigate the ability of SFDI to discriminate superficial scattering contrast in tissue simulating phantoms and in surgical breast tissues. Higher spatial frequencies were probed to increase sensitivity to scattering by tissue ultra-structure because recent results suggest this is most reliable for tissue type discrimination,47 and scattering was observed to display a more localized phenotype, as compared to absorption phenomena. Evaluation of scattering contrast in tissue-simulating phantoms showed that an inclusion as small as 1.25 mm in diameter was detectable for scattering contrast at least 28% and up to 7% scattering contrast was detected for a 10 mm inclusion; additionally, up to 33% scattering contrast was detectable at depths of 1.5 mm. This spatial resolution is sufficient to detect invasive cancers too large for effective eradication by radiation therapy. Accuracy of the diffusion approximation is known to be limited at high spatial frequencies by the restriction of no radiant anisotropy within the optical medium; here, the higher order approximation to the scattering phase function employed by Monte Carlo improved absorption quantification accuracy in breast tissues for near-source recovery of nondiffusive optical parameters.48 Functional absorption parameters could complement information provided by spectroscopic scattering, but the accuracy of their quantification may be improved by increasing the density of spectral sampling in the NIR and by acquiring more data at low spatial frequencies. Here, system analysis of SFDI highlights the depth selectivity of this planar acquisition geometry and explores the limitations of its contrast-detail resolution, model-data goodness of fit evaluated in surgical breast tissues, and the accuracy of optical parameter quantification. In the spatial frequency domain, effective attenuation, and consequently probing depth, , is a product of both the effective attenuation coefficient, , and the illumination modulation frequency, , such that . Consequently, light is attenuated more rapidly at high spatial frequencies yielding superficial interrogation of the specimen. At high spatial frequencies, the transport coefficient, , is the primary source of optical contrast. In the diffusion limit, this is predominantly a scattering signature. Sampling with a modulation frequency up to , we demonstrated an ability to detect up to 33% scattering contrast at the maximum depth relevant to surgical margin assessment (1.5 mm). The analytical solution to the diffusion approximation in the spatial frequency domain1 reveals that reflectance behaves as an inverse function of the ratio, . Consequently, at low spatial frequencies, absorption dominates optical contrast and there is a relatively deeper interrogation depth. The camera resolution and the number of sources (or spatial frequencies projected per sample) additionally influence detectable contrast. Finally, absolute quantification of optical parameters requires a repeatable, stable calibration phantom with known optical properties and all measures must be made at a uniform height because the reflectance amplitude decays according to an inverse square law. A three-phase amplitude de-modulation scheme has been developed to correct for surface profile changes,49 but continued efforts are needed to standardize calibration phantoms across institutions. An ability to detect small foci of DCIS would be significant clinically because DCIS is typically nonpalpable and its presence critically impacts the planning of gross resection margins, a significant factor affecting long-term patient care.50 DCIS is typified by high-grade epithelial proliferation in the lumen (which may or may not be associated with necrosis and micro-calcifications) and fibrosis in the periductal stroma.51 It is clinically treated as a preinvasive lesion, even though it is not clear that all DCIS lesions progress to the invasive type. Contrast-detail assessment in tissue-simulating phantoms suggests that superficial clusters of DCIS, and not epithelial hyper-proliferation within a single lumen, are detectable by SFDI.52,53 However, the increased depths probed by SFDI evaluate wider margins appropriate for DCIS. Conceivably, SFDI could readily improve resection completeness during breast conserving surgery by providing subsurface optical assessment of pathology in resected tissues. Implementation of the scaled-Monte Carlo LUT significantly reduced the computational burden associated with iterative estimation of optical parameters to render data analysis feasible in the operative setting. Data acquisition could be improved by accounting for surface profile changes during optical parameter recovery, increasing spectral resolution in the visible-NIR, and developing inking strategies that improve coregistration of spectral images with paraffin histology. Coregistration would be more feasible if the surgeon applied inks subsequent to imaging, but prior to removal of the tissue from the imaging platform. That way, inks corresponding to each image field could be recorded for pathology correlation. Precise coregistration with pathology is only necessary to validate the technology—in the surgical setting, near real-time imaging feedback would enable the surgeon to rotate the specimen and resect additional tissues as necessary. Some research groups have developed compact enclosures to maintain specimen orientation while locally sampling tissue optical properties.54 Development of a similar device would require considerable scalability given the variation observed in resected tissue size/shape and would likely induce imaging artifacts for this illumination scheme. Edge artifacts were significantly observed in lumpectomy specimens prior to gross sectioning, but a three-phase amplitude de-modulation scheme has been developed to correct for surface profile changes49 and will be implemented in future studies. Translation of SFDI to surgical margin assessment should focus on improving image reconstruction speed, automating combined acquisition of tissue and phantom calibration data, and developing inking strategies for improved coregistration with pathology. 5.ConclusionsThe ultimate goal of conservative surgery is to remove enough primary cancer for effective eradication of microscopic residual disease by radiation therapy. Here, tissue-simulating phantoms with known properties were imaged for optimization of analysis methods to determine the microscopic sensitivity of SFDI. A 1.25 mm diameter inclusion was detectable when scattering contrast was at least 28%; a quarter of this scattering contrast (7%) was detectable for 10 mm inclusions and at least 33% scattering contrast was detected up to 1.5 mm in depth. Relative trends in the spectral scattering amplitude and slope were conserved and recovered scattering parameters demonstrated insensitivity to hemoglobin changes. Recovered hemoglobin concentrations demonstrated insensitivity to changes in scattering, except at low hemoglobin concentrations (), where they were overestimated at visible wavelengths, but within of their true range. The scattering amplitude increased linearly with scattering concentration, but the scattering slope depended on both the particle size and number density. Absorption parameters extracted using scaled-Monte Carlo simulations of light transport varied most linearly with expected hemoglobin concentration in liquid phantoms and minimized information loss when fitting reflectance spectra acquired from surgical breast tissues at higher spatial frequencies. Data acquisition was ultimately tested in four fully intact, lumpectomy tissues and a workflow was established for acquisition and analysis to facilitate the clinical translation of this technology to breast conserving surgery. The primary challenges observed with the clinical translation of SFDI were: edge artifacts induced by tissue surface profile changes and orienting spectroscopic images with pathology to validate margin status; these may be overcome by surface profile correction algorithms and inking strategies coordinated with the surgeon. SFDI has the potential to effectively detect tissue subtypes in surgical breast lesions because it maintains sensitivity to local scattering contrast over a wide field and data is acquired in a noncontact geometry. AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to thank Kari Rozenkranz MD and Burt Eisenberg MD in the Department of Surgery, and Vincent Memoli MD, Candice Black DO, Xiaoying Liu MD, and Laura Tafe MD in the Department of Pathology, at Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center for their help procuring and processing breast surgical specimens. This work was supported by the NIH support R21RR024411, PO1CA80139 and P41EB015890 (Laser Microbeam and Medical Program, LAMMP), and the Department of Defense BC093811. ReferencesD. J. Cucciaet al.,

“Quantitation and mapping of tissue optical properties using modulated imaging,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 14

(2), 024012

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3088140 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

T. H. Phamet al.,

“Quantifying the properties of two-layer turbid media with frequency-domain diffuse reflectance,”

Appl. Opt., 39

(25), 4733

–4745

(2000). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.39.004733 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

M. CanpolatJ. R. Mourant,

“Particle size analysis of turbid media with a single optical fiber in contact with the medium to deliver and detect white light,”

Appl. Opt., 40

(22), 3792

–3799

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.40.003792 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

L. T. Perelmanet al.,

“Observation of periodic fine structure in reflectance from biological tissue: a new technique for measuring nuclear size distribution,”

Phys. Rev. Lett., 80

(3), 627

–630

(1998). http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.627 PRLTAO 0031-9007 Google Scholar

R. L. P. van Veenet al.,

“Optical biopsy of breast tissue using differential path-length spectroscopy,”

Phys. Med. Biol., 50

(11), 2573

–2581

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/50/11/009 PHMBA7 0031-9155 Google Scholar

P. Thueleret al.,

“In vivo endoscopic tissue diagnostics based on spectroscopic absorption, scattering, and phase function properties,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 8

(3), 495

–503

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.1578494 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

R. ReifO. A’AmarI. J. Bigio,

“Analytical model of light reflectance for extraction of the optical properties in small volumes of turbid media,”

Appl. Opt., 46

(29), 7317

–7328

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.46.007317 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

J. R. Mourantet al.,

“Influence of the scattering phase function on light transport measurements in turbid media performed with small source-detector separations,”

Opt. Lett., 21

(7), 546

–548

(1996). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.21.000546 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

F. BevilacquaC. Depeursinge,

“Monte Carlo study of diffuse reflectance at source-detector separations close to one transport mean free path,”

J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, 16

(12), 2935

–2945

(1999). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/JOSAA.16.002935 JOAOD6 0740-3232 Google Scholar

F. Nguyenet al.,

“Intraoperative evaluation of breast tumor margins with optical coherence tomography,”

Cancer Res., 69

(22), 8790

–8796

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4340 CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

J. Brownet al.,

“Quantitative optical spectroscopy: a robust tool for direct measurement of breast cancer vascular oxygenation and total hemoglobin content in vivo,”

Cancer Res., 69

(7), 2919

–2926

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3370 CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

I. Bigioet al.,

“Diagnosis of breast cancer using elastic-scattering spectroscopy: preliminary clinical results,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 5

(2), 221

–228

(2000). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.429990 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

B. W. Pogueet al.,

“Quantitative hemoglobin tomography with diffuse near-infrared spectroscopy: pilot results in the breast,”

Radiol., 218

(1), 261

–266

(2001). RADLAX 0033-8419 Google Scholar

S. Srinivasanet al.,

“Interpreting hemoglobin and water concentration, oxygen saturation, and scattering measured in vivo by near-infrared breast tomography,”

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 100

(21), 12349

–12354

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2032822100 PNASA6 0027-8424 Google Scholar

S. Srinivasanet al.,

“Near-infrared characterization of breast tumors in vivo using spectrally-constrained reconstruction,”

Technol. Cancer Res. Treat., 4

(5), 513

–526

(2005). TCRTBS 1533-0346 Google Scholar

L. O. Svaasandet al.,

“Reflectance measurements of layered media with diffuse photon-density waves: a potential tool for evaluating deep burns and subcutaneous lesions,”

Phys. Med. Biol., 44

(3), 801

–813

(1999). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/44/3/020 PHMBA7 0031-9155 Google Scholar

J. R. Mourantet al.,

“Mechanisms of light scattering from biological cells relevant to noninvasive optical-tissue diagnostics,”

Appl. Opt., 37

(16), 3586

–3593

(1998). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.37.003586 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

A. KienleF. K. ForsterR. Hibst,

“Influence of the phase function on determination of the optical properties of biological tissue by spatially resolved reflectance,”

Opt. Lett., 26

(20), 1571

–1573

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.26.001571 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

T. J. FarrellM. S. PattersonB. Wilson,

“A diffusion theory model of spatially resolved, steady-state diffuse reflectance for the noninvasive determination of tissue optical properties in vivo,”

Med. Phys., 19

(4), 879

–888

(1992). http://dx.doi.org/10.1118/1.596777 MPHYA6 0094-2405 Google Scholar

N. DognitzG. Wagnieres,

“Determination of tissue optical properties by steady-state spatial frequency-domain reflectometry,”

Laser. Med. Sci., 13

(1), 55

–65

(1998). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF00592960 LMSCEZ 1435-604X Google Scholar

A. Kimet al.,

“A fiberoptic reflectance probe with multiple source-collector separations to increase the dynamic range of derived tissue optical absorption and scattering coefficients,”

Opt. Express, 18

(6), 5580

–5594

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.18.005580 OPEXFF 1094-4087 Google Scholar

J. Sunet al.,

“Influence of fiber optic probe geometry on the applicability of inverse models of tissue reflectance spectroscopy: computational models and experimental measurements,”

Appl. Opt., 45

(31), 8152

–8162

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.45.008152 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

J. C. FinlayT. H. Foster,

“Hemoglobin oxygen saturations in phantoms and in vivo from measurements of steady-state diffuse reflectance at a single, short source-detector separation,”

Med. Phys., 31

(7), 1949

–1959

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1118/1.1760188 MPHYA6 0094-2405 Google Scholar

R. Graaffet al.,

“Condensed Monte Carlo simulations for the description of light transport,”

Appl. Opt., 32

(4), 426

–434

(1993). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.32.000426 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

A. KienleM. S. Patterson,

“Determination of the optical properties of turbid media from a single Monte Carlo simulation,”

Phys. Med. Biol., 41

(10), 2221

–2227

(1996). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/41/10/026 PHMBA7 0031-9155 Google Scholar

R. Pleijhuiset al.,

“Obtaining adequate surgical margins in breast-conserving therapy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: current modalities and future directions,”

Ann. Surg. Oncol., 16

(10), 2717

–2730

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0609-z 1068-9265 Google Scholar

“Cancer Facts and Figures,”

(2011). Google Scholar

U. Veronesiet al.,

“Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer,”

New Engl. J. Med., 347

(16), 1227

–1232

(2002). http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa020989 NEJMBH 0028-4793 Google Scholar

B. Fisheret al.,

“Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer,”

New Engl. J. Med., 347

(16), 1233

–1241

(2002). NEJMBH Google Scholar

C. D. Scopaet al.,

“Evaluation of margin status in lumpectomy specimens and residual breast carcinoma,”

Breast J., 12

(2), 150

–153

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00223.x BRJOFK 1075-122X Google Scholar

S. J. Schnittet al.,

“The relationship between microscopic margins of resection and the risk of local recurrence in patients with breast cancer treated with breast-conserving surgery and radiation therapy,”

Cancer, 74

(6), 1746

–1751

(1994). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142 60IXAH 0008-543X Google Scholar

B. Spivacket al.,

“Margin status and local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery,”

Arch. Surg.-Chicago, 129

(9), 952

–956

(1994). http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.1994.01420330066013 ARSUAX 0004-0010 Google Scholar

M. Clarkeet al.,

“Effects of radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials,”

Lancet, 366

(9503), 2087

–2106

(2005). LANCAO 0140-6736 Google Scholar

J. FerreiroJ. GisvoldD. Bostwick,

“Accuracy of frozen section diagnosis of mammographically detected breast biopsies; results of 1,490 consecutive cases,”

Am. J. Surg. Path., 19

(11), 1267

–1271

(1995). http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00000478-199511000-00006 AJSPDX 0147-5185 Google Scholar

J. TinnemansT. WobbesR. Holland,

“Mammographic and histopathologic correlation of non-palpable lesions of the breast and reliability of frozen section diagnosis,”

Surg. Gynecol. Obstet., 165

(6), 523

–529

(1987). SGOBA9 0039-6087 Google Scholar

G. Gibsonet al.,

“A comparison of ink-directed and traditional whole cavity re-excision for breast lumpectomy specimens with positive margins,”

Ann. Surg. Oncol., 8

(9), 693

–704

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10434-001-0693-1 1068-9265 Google Scholar

D. J. Cucciaet al.,

“Modulated imaging: quantitative analysis and tomography of turbid media in the spatial-frequency domain,”

Opt. Lett., 30

(11), 1354

–1356

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.30.001354 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

M. A. A. NeilR. JuskaitisT. Wilson,

“Method of obtaining optical sectioning by using structured light in a conventional microscope,”

Opt. Lett., 22

(24), 1905

–1907

(1997). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.22.001905 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

F. Bevilacquaet al.,

“Broadband absorption spectroscopy in turbid media by combined frequency-domain and steady-state methods,”

Appl. Opt., 39

(34), 6498

–6507

(2000). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.39.006498 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

A.-N. SpiessN. Neumeyer,

“An evaluation of R2 as an inadequate measure for nonlinear models in pharmacological and biochemical research: a Monte Carlo approach,”

BMC Pharmacol., 10

(6),

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2210-10-6 BPMHBU 1471-2210 Google Scholar

H. Akaike,

“New look at statistical model identification,”

IEEE Trans. Autom. Control, 19

(6), 716

–723

(1974). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705 IETAA9 0018-9286 Google Scholar

R. MichelsF. FoschumA. Kienle,

“Optical properties of fat emulsions,”

Opt. Express, 16

(8), 5907

–5925

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.16.005907 OPEXFF 1094-4087 Google Scholar

A. Mazharet al.,

“Wavelength optimization for rapid chromophore mapping using spatial frequency domain imaging,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 15

(6), 061716

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3523373 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

S. L. JacquesS. Prahl, Optical Properties Spectra, Oregon Medical Laser Center, Portland, Oregon

(2010). Google Scholar

B. W. PogueM. S. Patterson,

“Review of tissue simulating phantoms for optical spectroscopy, imaging and dosimetry,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 11

(4), 041102

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.2335429 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

B. Pogueet al.,

“Characterization of hemoglobin, water, and NIR scattering in breast tissue: analysis of intersubject variability and menstrual cycle changes,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 9

(3), 541

–552

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.1691028 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

T. M. Bydlonet al.,

“Advancing pptical imaging for breast margin assessment: an analysis of excisional time, cautery, and patent blue dye on underlying sources of contrast,”

PLoS One, 7

(12), e51418

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051418 1932-6203 Google Scholar

S. D. Koneckyet al.,

“Imaging scattering orientation with spatial frequency domain imaging,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 16

(12), 126001

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3657823 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

S. Giouxet al.,

“Three-dimensional surface profile intensity correction for spatially modulated imaging,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 14

(3), 034045

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3156840 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

W. A. Wellset al.,

“Phase contrast microscopy analysis of breast tissue differences in benign vs. malignant epithelium and stroma,”

Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol., 31

(4), 197

–207

(2009). AQCHED 0884-6812 Google Scholar

E. B. Clauset al.,

“Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ,”

JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc., 293

(8), 964

–969

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.8.964 JAMAAP 0098-7484 Google Scholar

A. M. Laughneyet al.,

“Scatter spectroscopic imagin distinguishes breast pathologies in tissues relevant to surgical margin assessment,”

Clin. Cancer Res., 18

(22), 6315

–6325

(2012). CCREF4 1078-0432 Google Scholar

A. M. Laughneyet al.,

“Automated classification of breast pathology using local measures of broadband reflectance,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 15

(6), 066019

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3516594 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

J. Q. Brownet al.,

“Intraoperative optical breast tissue characterization device for tumor margin assessment,”

Cancer Res., 69

(2), 101s

–101s

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS-801 CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

|