|

|

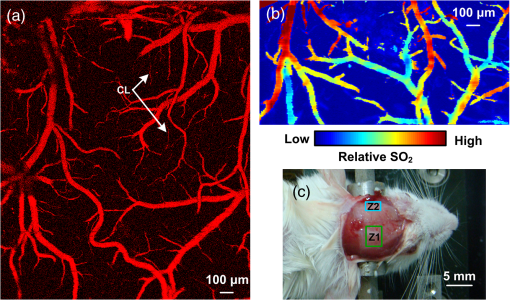

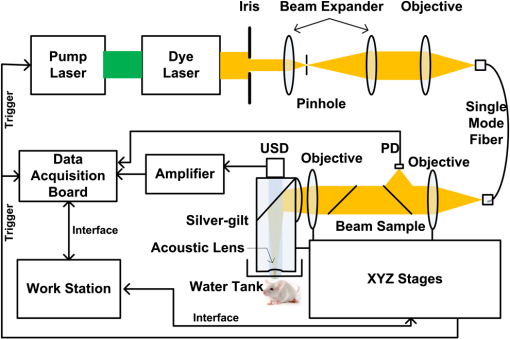

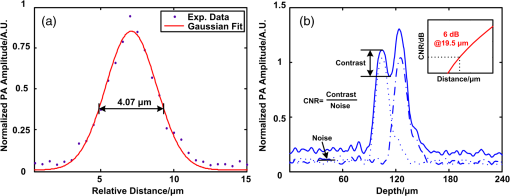

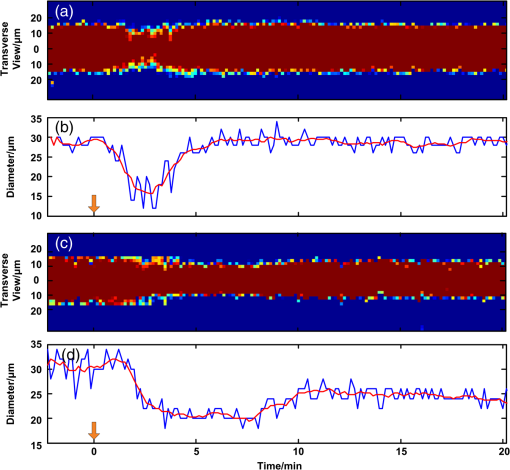

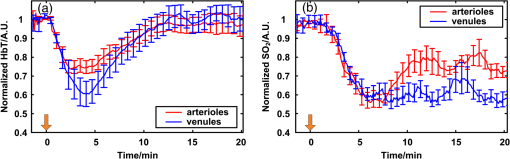

1.IntroductionPatients with acute bacterial meningitis1 and septic shock2 are normally treated with vasoactive drugs to increase mean arterial pressure to preserve adequate organ perfusion. Such drugs interact with specific vessel receptors, which hereafter alters the vascular morphology,3 blood flow, and brain oxygen dynamics.4,5 The morphological changes of cerebral microvessels may alter the perfusion to the brain. The hemodynamic parameters, such as total hemoglobin (HbT) and of cerebral microvessels, partially reflect the oxygen supply and consumption of brain tissue. As the brain has a much higher demand for oxygen, although vessel diameter and blood flow may recover shortly under autoregulation,6 the alteration of oxygen supply may cause unrecoverable damage in the brain and even behavioral disorders.7 In order for a comprehensive evaluation of effects of vasoactive drugs such as norepinephrine, in vivo high resolution simultaneous monitoring of the cerebral microvascular morphology and hemodynamics is recommended.8 Clinical imaging modalities, such as X-ray CT9 and ultrasonography,10 have been used widely but need exogenous contrast agents for vascular imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging11 can map the structure and function of the brain but still struggle to resolve the microvasculature. With variable intrinsic optical contrast, optical imaging modalities have been used for cerebral blood vessel imaging. Near-infrared spectroscopy12 (NIRS) and diffuse optical tomography13 can monitor the deep brain tissue hemodynamic but still do not guarantee the ability to resolve microvasculature. Laser speckle imaging14 can map the microvascular blood flow velocity, but hemodynamic parameters such as HbT and are missing. Confocal microscopy15 and two-photon microscopy16 can map cerebral microvasculature with submicron resolution, but exogenous fluorescence agents are necessary. Optical coherence tomography17 has been used to map the three-dimensional (3-D) volumetric cerebral microvascular structure and blood flow combined with Doppler effect but still lack the oxygen saturation information. Photoacoustic microscopy detects laser-induced acoustic waves, which reveals solely optical absorption contrast. In the visible spectral region, the absorption coefficient of blood is much higher than that of surrounding tissue, which makes photoacoustic microscopy a superior modality for blood vessel imaging.18 By irradiating the brain cortex with a tightly focused light, photoacoustic microscopy can map microvasculature with high resolution.19 With two or more wavelengths, photoacoustic microscopy can map the cerebral microvascular morphology and oxygen saturation simultaneously.20 Here, we utilized an optical-resolution photoacoustic microscope to simultaneously monitor the morphological and hemodynamic changes in healthy mice brain cortex microvessels during the injection of norepinephrine. By one-time injection of norepinephrine, we monitored the changes of microvascular diameter, HbT, and due to instantaneous high drug concentration. We also evaluated the recovery process of the three parameters without further drug injection. 2.Materials and Methods2.1.System DescriptionFigure 1 shows the experimental setup of the optical-resolution photoacoustic microscope for in vivo imaging of cerebral microvasculature. A dye laser (Credo, Sirah Laser und Plasmatechnik, Germany) pumped by a Nd:YLF laser (IS8II-E, EdgeWave GmbH, Germany) was employed as the wavelength-tunable irradiation source. It provided laser pulses with a pulse width of 9 ns and a pulse repetition of 1 KHz. Laser beam from the dye laser was focused by a set of plano-convex lens and then filtered by a 50-μm diameter pinhole. An objective lens was used to focus the laser beam into a single-mode fiber (core diameter: 3.5 μm). Laser beam from the distal end of the fiber was focused into the brain cortex by a long working distance objective lens (NT46-143, Edmund Optics, , working distance: 34 mm), after being collimated by another same objective lens. The incident energy density on the brain cortex was estimated to be , which was slightly smaller than the American National Standards Institute safety limit21 ( in the visible spectral region). Fig. 1Schematic of the optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy system. USD: ultrasonic transducer, PD: photodetector.  A home-made prism which contained a silver gilt with a 45 deg inclined plane was used for acoustic-optical coaxial alignment.22 The inclined plane reflected the incident laser beam, while a contact ultrasound transducer (V2022, Olympus, central frequency: 75 MHz) detected acoustic waves transmitted through the prism. An acoustic lens was ground in the bottom of the prism for acoustic focusing, and a plano-convex lens was inserted before the laser beam incident into the prism for correcting the divergence when laser beam passed through the acoustic lens. The prism we designed provided a more effective way to detect acoustic signals because it avoided the transformation from longitudinal acoustic wave to shear wave when the acoustic wave was reflected. The imaging head was mounted on a three-axis linear stage, of which the axis was used to adjust the focal plane. 3-D imaging was implemented combining time-resolved acoustic detection and two-dimensional raster scan. The data acquisition card (ATS9350, Alazartech, Canada) recorded both photoacoustic signal and photodetector signal, which indicated the deviation of incident laser energy, using a sample rate of 500 MHz. The lateral and axial resolutions were estimated by imaging carbon nanoparticles with a mean diameter of 100 nm, as illuminated in Fig. 2. The Gaussian fit to the transverse profile of a carbon nanoparticle gave an estimation of the lateral resolution to be 4.07 μm [Fig. 2(a)]. The axial resolution was estimated by applying shift-and-sum to the Hilbert transform of the axial profile of carbon nanoparticle [Fig. 2(b)]. The contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) curve [inset of Fig. 2(b)] was applied for the estimation of axial resolution.23 Here, the contrast was defined as the difference between the smaller of the two peaks and the valley. The noise was defined as the standard deviation of the experimental measurement without absorbers. According to Rayleigh criterion, the axial resolution was defined to be the distance where the CNR equaled 6 dB. The axial resolution was estimated to be 19.5 μm from the CNR curve. Fig. 2Resolution estimation of the optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy system. (a) Transverse spread profile of a typical carbon nanoparticle. Red line indicates the Gaussian fit to the experimental data. (b) Simulated photoacoustic shift-and-sum signals. The dot line and dash-dot line indicate two nanoparticles with a distance of 20 μm. The solid line indicates the overlap of photoacoustic signals of the two nanoparticles. The inset shows the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) versus the shift distance when summing two nanoparticle signals.  2.2.Animal PreparationExperiments were performed on mice (25 to 30 g, 5 week, Animal Biosafety Level 3 Laboratory, Wuhan, China). Before each experiment, a mouse was anesthetized by intraperitoneally administering a dose of chloral hydrate and urethane. During the anesthesia, the body temperature of the mouse was kept at 37°C by a temperature stabilized heating pad. The mouse was fixed on a brain stereotactic apparatus to avoid motion disturbance. One dorsal portion of the skull was removed using a dental drill after removing the scalp and temporal muscle over it, thus a cranial opening () was implemented and the dura mater was exposed. A thin layer of artificial cerebrospinal fluid was implemented on the dura mater before the ultrasonic gel was applied to keep the appropriate biochemical environment. During each experiment, we first used an isosbestic wavelength of 584 nm to image the cerebral microvascular structure through the cranial opening. Then, we randomly chose a cross-sectional scan along the rostral direction. The scan length was about 2 mm which covered both arterioles and venules. The selected cross scan was used for dynamic monitoring of the diameter, HbT, and during the injection of norepinephrine. Three wavelengths of 576, 580, and 584 nm were used for the monitoring. Each monitoring trial lasted for (150 B-scans at three wavelengths). During the first 2 to 3 min, the mouse stayed calm, and we could get the base line. Then, 100 μL of norepinephrine bitartrate (, A0937, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was injected through tail vein in six of the eight mice. The other two mice were injected with 100 μL physiological saline as the control trials. The monitoring went on throughout the injection and lasted for 20 min after injection. After each experiment, the mouse was euthanized with an overdose of pentobarbital. All the procedures in the experiments were carried out in according to the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hubei Province. 2.3.Data AnalysisAfter the experiment, amplitudes of photoacoustic signal were extracted via Hilbert transform and no other data processing was required. In order to extract the vessels from the background, we considered pixels with an amplitude, i.e., 3 dB, above the standard deviation of the noise to be vessels.24 In this way, we could count the number of vessel pixels from the transverse view. Since we scanned the B line with a step size of 2 μm, the vessel diameter could be roughly calculated. Images acquired under the wavelength of 584 nm mapped the distribution of HbT. Referring to the vascular region obtained above, pixels within the same vessel at the same time were averaged. The relative change was further calculated by normalized to the base value. Oxygen saturation of the microvessels can be calculated using a multiwavelength method.25 Deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR) and oxygenated hemoglobin () were treated to be the dominant absorbing compounds in blood. Using more than two wavelengths, we can get the following by least-squares fitting. whereis the proportionality coefficient that is considered to be constant. is the molar extinction coefficient. is the amplitude of photoacoustic signal. Further data processing was the same as that used in HbT to get the relative change in . In order for temporal characterization of the response, we quantified the response times from the injection time, until one parameter (i.e., diameter, HbT) monotonically changed from a relatively stable state to 10% of the maximum response. In each trial, the injection time was set to be 0. As each line scan under three wavelengths costs about 9 s, we can quantify the response times (units: minute) to be as follows: where was the differential scan line index during the quantification.3.Results3.1.Imaging of Mouse Cerebral MicrovasculatureFigure 3(a) shows the maximum amplitude projection of region of interest (ROI) Z1 depicted in Fig. 3(c). The imaging wavelength was 584 nm, where HbR and have nearly the same molar extinction coefficient. Therefore, the image mainly mapped the concentration of HbT that was independent of blood oxygen level. Figure 3(a) gave a good visualization of the branch structures. The minimum resolvable vasculature in Fig. 3(a) covered 3 to 4 pixels. Considering that the pixel size used here was 2 μm, the minimum resolvable vasculature [marked with CL in Fig. 3(a)] was 6 to 8 μm, which was probably the single capillary vessel. Multiwavelength photoacoustic imaging was conducted in ROI Z2. Three wavelengths were chosen, of which 584 nm is the isosbestic wavelength reflecting the distribution of HbT (), and 576 and 580 nm are absorption-dominant wavelength reflecting mainly the distribution of . Meanwhile, the relatively high absorption coefficient of whole blood at the three wavelengths guaranteed the high signal-to-noise ratio. The commonly used arithmetic mean filter (window size: ) was applied to the calculated value and the value was visualized with pseudocolors ranging from blue to red, depicted in Fig. 3(b). The red vessels were most probably arterioles, and the blue ones were likely venules. According to the mouse brain anatomy, the region labeled Z2 has the characterization where branch arterioles from the middle cerebral artery and venules from superior sagittal sinus intersect with each other,26 which is consistent with our result. 3.2.Changes of Cerebral Microvascular DiameterMost of the microvessels under investigation exhibited obvious vasoconstriction immediately after the injection. Vasoconstriction reached the maximum after 3 min. The microvessesls began to recover after severe vasoconstriction which lasted for 2 to 4 min. Normally, the microvessels recovered back to the resting state 7 min after the injection. However, some microvessels sustained a slight contraction throughout the investigation. Figure 4 illustrates typical changing of microvascular morphology during the observation. Figure 4(a) and 4(c) is the transverse view of the morphological changes of an arteriole and a venule, respectively, during the injection of norepinephrine. The horizontal axis shows the time course, and the vertical axis marks the semidiameter along the center of the microvessels. Figure 4(b) and 4(d) is the plot of the diameter of the arteriole and the venule mentioned above, where the blue line shows the raw data, and the red line shows the tendency of the blue line after the application of a mean filter. The arithmetic mean filter set the center point values to be the average of an 8-pixel neighborhood and signals beyond the end points were set to be 0. Both the microvessels constricted severely immediately after injection, reached a constriction stabilization period after about 2.5 min, and recovered thereafter. There are still some differences between the responses of arteriole and venule. The arteriole constricted from 30 μm to a minimum diameter of 15 μm, whereas the venule constricted from 32 μm to a minimum diameter of 22 μm. The constriction ratio of arteriole and venule, which was defined as 1-minimum diameter/resting state diameter, was 50% and 31.25%, respectively. By the end of the observation, the diameter of the arteriole recovered back to the same as the resting state, while the venule preserved a slightly smaller diameter. Ten arterioles and ten venules were conducted in statistical analysis, respectively. The arterioles constricted to a minimum diameter that is of the resting state, whereas the venules reached only , showing a significant difference (). By the end of the observation, the diameter of arterioles recovered to of the base value, the venules only back to , showing a significant statistical difference (). In the control trials, no changes of diameter were observed throughout the observation, indicating that the observed phenomenon was not the effect of tail vein injection of exogenous reagents. The observations suggested that cerebral microvasculature of healthy mice constricted severely when intravenously injected with norepinephrine, but recovered in a short time without prolonged drug injection thereafter. The arterioles exhibited more intense constriction than venules. Fig. 4Changes of cerebral microvascular diameter during investigation. (a) and (c) shows the transverse view of a typical arteriole and venule during the observation, the vertical axis marks the semidiameter from the center of vessels. (b) and (d) are diameter plots of arteriole in (a) and venule in (c), the blue line indicates the raw data and the red line indicates the tendency of changes in diameter. Horizontal axis of all figures is the same time course, and the injection time is set to be 0 (indicated by arrow flag).  3.3.Changes of Cerebral Microvascular HbT andStatistical analysis was conducted on the 10 arterioles and 10 venules, respectively, to get the response of HbT and . The statistical results were illustrated in the form of error of mean (SEM) in Fig. 5. For better visualization, markers of SEM were drawn at only one point every half minute. Figure 5(a) depicted the changes of microvascular HbT during the investigation. Both arterioles and venules showed an immediate decreased HbT along with the vasoconstriction, 4 min after the injection arterioles reached a minimum of of the base value, meanwhile venules reached , showing a significant difference (). Thereafter, all of the vessels showed a slow increased HbT, and they recovered to the base value about 13 min after the injection. No significant difference between HbT in arterioles and that in venules was observed by the end of the observation. The above observations indicated that HbT in cerebral microvasculature decreased shortly after the vasoconstriction, venules showing a more severe response. But all of the microvessels recovered to the base value without further injection. Fig. 5Changes of cerebral microvascular (a) HbT and (b) during investigation. Red line indicates the changes of arterioles; blue line indicates the changes of venules. The injection time is set to be 0 (indicated by arrow flag).  Changes of cerebral microvascular were a little bit later than that of diameter and HbT, as illustrated in Fig. 5(b). in arterioles was before the injection and declined about 1.5 min after the injection of norepinephrine, reaching a minimum of . Finally, it fluctuated at after a slight increase. in venules was before the injection. Compared with arterioles, in venules showed a slight later decline, reaching a minimum of . It kept fluctuating at this level without the tendency of recovery. In the control trials, no changes of HbT and were observed throughout the observation. The observations indicated that a one-time injection with high dosage norepinephrine caused a serious decline in of cerebral microvasculature immediately. Although the will slightly increase in the arterioles, it sustained a low level in venules for a long time even without any further drug administration. 4.DiscussionIn clinical treatments, a high dosage of norepinephrine is intravenously administered to increase the mean artery pressure and then a decreased dosage is administered to maintain the mean artery pressure. In this manuscript, by one-time injection of high dosage norepinephrine,27 we simulated the early clinical treatment to monitor the cerebral microvascular response. According to research on the fate of norepinephrine,28 the norepinephrine disappeared in a short time without further injection, so we can also monitor the recovery process thereafter. Ritsuko Takahashi et al.29 microperfused arterioles from deep gray matter of rats. They found that norepinephrine caused a dose-dependent vasoconstriction when the concentration exceeded . Wahl et al.30 added norepinephrine to the perivascular space with micropipettes and observed the cerebral vasoconstriction. They further demonstrated that there were norepinephrine receptors on the pial arterial smooth muscle cells. In our trials, an instantaneous high concentration of norepinephrine was implemented. This indicated that the drugs effectively interacted with -adrenergic receptors31 and caused vasoconstriction. Without further drug injection, norepinephrine disappeared gradually and the smooth muscle relaxed, causing the cerebral vasculature to recover. Traditional clinical modalities mainly monitor the systemic oxygen saturation, which are not suitable for brain oxygen level monitoring. MacKenzie et al.32 took cerebral arterial and venous blood samples to analyze the oxygen hemodynamics. They found that when opening the blood–brain barrier, intracarotid injection of norepinephrine at a dosage of caused an increase of 21% in cerebral oxygen consumption. Brassard et al.33 utilized NIRS to monitor the cerebral cortex response to the injection of norepinephrine in healthy human beings. They found that frontal lobe oxygen saturation decreased with the injection of high dosage norepinephrine. Further, higher dosage caused more decrease in oxygen saturation in the frontal lobe. Our results were consistent with the above literatures. Furthermore, the photoacoustic microscopy provided moderate temporal resolution, which permitted the monitoring of rapid morphological and hemodynamical changes. This phenomenon can be partially explained combined with changes in diameter. The severe vasoconstriction caused by norepinephrine increased the vascular resistance to blood flow, further reduced the perfusion to brain tissue, and finally caused a reduction in HbT and .34 Without further drugs injected, microvascular diameter and HbT recovered in turn, reflecting a normal oxygen supply to brain. But the brain tissue still underwent a high oxygen consumption, which prevented from recovering. Compared with existing research, photoacoustic microscopy can map the microvessels even single capillaries, which facilitates the in vivo monitoring of single cerebral microvessels dynamically. It is worth noting that our results showed a higher change of compared to the literatures mentioned. There may be two reasons. First, the photoacoustic microscopy has a much higher spatial resolution than traditional functional imaging modalities. As we have demonstrated, we monitored at single microvessels instead of the average value of vessels in a certain region. Second, the photoacoustic imaging of blood vessels solely depends on the different optical absorption between blood and surrounding tissue, which guarantees the monitor to be more specific and sensitive.35 In our experiment, we also observed some different arteriovenous responses. The arterioles had a bigger constriction ratio than venules 2.5 min after the injection. This may reflect the distinct anatomical features that rich smooth muscle in arterioles has, but poorer in venules.36 The maximum changes of HbT in arterioles were a little bit smaller than that in venules, which may be caused by different blood flow changes due to vasoconstriction. Without further drugs injected, there was a slight increase of in arterioles only. We considered that the high oxygen consumption of the whole body37 decreased the in venules and in turn affected arterioles. On the other hand, the contraction of bronchus38 in response to norepinephrine restricted the efficiency of oxygen exchange during breath, thereby preventing the rapid recovery of . Meanwhile, the oxygen consumption of brain tissue was still high. As a result, the venules showed a lower than arterioles. In our experiments, multiple parameters were obtained simultaneously; therefore, we were able to access the time course of different parameters. It reflected the causal relationship between hemodynamic and oxygen metabolism and helped us to assess the mechanism of drugs. To be clear, the change of HbT we monitored reflected the redistribution of red blood cells in the imaging vessels39 but not the change of hemoglobin concentration in single red blood cells. Although the tiny laser spots permitted acoustic stimulation in single red blood cells, the scan speed (2 mm/s) and scan mode (linear scan) did not guarantee the ability to trace single red blood cells. Combining Figs. 4 and 5, we can see that the diameter changes came first, then HbT declined, and finally decreased. We believe that the direct effect of norepinephrine is to cause vasoconstriction, and changes in HbT and are the consequences of vasoconstriction. There was a severe vasoconstriction during the early time of injection. Although blood flow changed to compensate for the disturbance to steady state, it still leads to an insufficient cerebral microvascular perfusion and then a decrease in HbT.40 The decrease in HbT caused a cut down in oxygen supply, therefore a decrease happened in . During the recovery period, the diameter and HbT recovered to the base value. But by the end of the observation, there was no sign that would recover. This may indicate that, in our trials, the brain tissue still underwent a high oxygen consumption.41 Multiwavelength photoacoustic microscopy was utilized to conduct high spatio-temporal resolution and multiparameter monitoring on healthy mice cerebral microvasculature during the injection of norepinephrine. The method can be used for an early and a comprehensive monitoring of brain physiological state, assessing the effects during the treatment. On the other hand, the parameters mentioned in the article are still insufficient to reveal the reasons of all the phenomena. By utilizing photoacoustic Doppler imaging42 and oxygen sensitive dye,43 the simultaneous measurements of blood flow and oxygen partial pressure will give us a brighter view of the mechanism. 5.ConclusionWe have designed and implemented a photoacoustic microscope for cerebral microvascular structure and oxygen saturation mapping. Diameter, HbT, and changes of cerebral microvessels have been successfully monitored during the injection of norepinephrine. Therefore, the photoacoustic microscopy holds the potential to be a method for evaluating the drug effects on brain. AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by National Key Technology R&D Program (Grant No. 2012BAI23B02) and Science Fund for Creative Research Group (Grant No. 61121004). ReferencesK. Molleret al.,

“Cerebral blood flow and metabolism during infusion of norepinephrine and propofol in patients with bacterial meningitis,”

Stroke, 35

(6), 1333

–1339

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.STR.0000128418.17312.0e SJCCA7 0039-2499 Google Scholar

S. Jhanjiet al.,

“The effect of increasing doses of norepinephrine on tissue oxygenation and microvascular flow in patients with septic shock,”

Crit. Care Med., 37

(6), 1961

–1966

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a00a1c CCMDC7 0090-3493 Google Scholar

E. A. SchenkA. J. Moss,

“Cardiovascular effects of sustained norepinephrine infusions. II. Morphology,”

Circ. Res., 18

(5), 605

–615

(1966). http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.18.5.605 CIRUAL 0009-7330 Google Scholar

J. LeBlancet al.,

“Metabolic and cardiovascular responses to norepinephrine in trained and nontrained human subjects,”

J. Appl. Physiol., 42

(2), 166

–173

(1977). JAPYAA 0021-8987 Google Scholar

A. J. MossI. VittandsE. A. Schenk,

“Cardiovascular effects of sustained norepinephrine infusions. I. Hemodynamics,”

Circ. Res., 18

(5), 596

–604

(1966). http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.18.5.596 CIRUAL 0009-7330 Google Scholar

S. E. DowningE. H. Sonnenblick,

“Effects of continuous administration of angiotensin II on ventricular performance,”

J. Appl. Physiol., 18

(3), 585

–592

(1963). JAPYAA 0021-8987 Google Scholar

Y. Akiyamaet al.,

“Effects of hypoxia on the activity of the dopaminergic neuron system in the rat striaturn as studied by in vivo brain microdialysis,”

J. Neurochem., 57

(3), 997

–1002

(1991). http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jnc.1991.57.issue-3 JONRA9 0022-3042 Google Scholar

B. D. KingL. SokoloffR. L. Wechsler,

“The effects of l-epinephrine and l-norepinephrine upon cerebral circulation and metabolism in man,”

J. Clin. Invest., 31

(3), 273

–279

(1952). http://dx.doi.org/10.1172/JCI102603 JCINAO 0021-9738 Google Scholar

A. S. Makladet al.,

“Extraction of liver volumetry based on blood vessel from the portal phase CT dataset,”

Proc. SPIE, 8314 83142O

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/12.911175 PSISDG 0277-786X Google Scholar

N. Y. Zhanget al.,

“High-resolution fMRI mapping of ocular dominance layers in cat lateral geniculate nucleus,”

Neuroimage, 50

(4), 1456

–1463

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.01.053 NEIMEF 1053-8119 Google Scholar

C. M. Baumgartneret al.,

“Cardiovascular effects of dipyrone and propofol on hemodynamic function in rabbits,”

Am. J. Vet. Res., 70

(11), 1407

–1415

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.2460/ajvr.70.11.1407 AJVRAH 0002-9645 Google Scholar

J. H. Zhaiet al.,

“Hemodynamic and electrophysiological signals of conflict processing in the Chinese-character Stroop task: a simultaneous near-infrared spectroscopy and event-related potential study,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 14

(5), 054022

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3247152 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

J. P. Culveret al.,

“Volumetric diffuse optical tomography of brain activity,”

Opt. Lett., 28

(21), 2061

–2063

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.28.002061 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

P. C. Liet al.,

“Imaging cerebral blood flow through the intact rat skull with temporal laser speckle imaging,”

Opt. Lett., 31

(12), 1824

–1826

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.31.001824 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

E. Laemmelet al.,

“Fibered confocal fluorescence microscopy (Cell-viZio (TM)) facilitates extended imaging in the field of microcirculation—a comparison with intravital microscopy,”

J. Vasc. Res., 41

(5), 400

–411

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000081209 JVREE9 1018-1172 Google Scholar

M. J. Leveneet al.,

“In vivo multiphoton microscopy of deep brain tissue,”

J. Neurophysiol., 91

(4), 1908

–1912

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1152/jn.01007.2003 JONEA4 0022-3077 Google Scholar

Y. M. Wanget al.,

“In vivo total retinal blood flow measurement by Fourier domain Doppler optical coherence tomography,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 12

(4), 041215

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.2772871 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

H. F. ZhangK. MaslovL. H. V. Wang,

“In vivo imaging of subcutaneous structures using functional photoacoustic microscopy,”

Nat. Protoc., 2

(4), 797

–804

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2007.108 NPARDW 1750-2799 Google Scholar

K. Maslovet al.,

“Optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy for in vivo imaging of single capillaries,”

Opt. Lett., 33

(9), 929

–931

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.33.000929 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

S. Huet al.,

“Functional transcranial brain imaging by optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 14

(4), 040503

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3194136 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

American National Standard for Safe Use of Lasers ANSI Z136.1-2000, American National Standards Institute, Inc., Orlando

(2000). Google Scholar

S. HuK. MaslovL. V. Wang,

“Second-generation optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy with improved sensitivity and speed,”

Opt. Lett., 36

(7), 1134

–1136

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.36.001134 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

C. Zhanget al.,

“In vivo photoacoustic microscopy with 7.6-mu m axial resolution using a commercial 125-MHz ultrasonic transducer,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 17

(11), 116016

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.17.11.116016 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

V. Tsytsarevet al.,

“Photoacoustic microscopy of microvascular responses to cortical electrical stimulation,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 16

(7), 076002

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3594785 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

H. F. Zhanget al.,

“Imaging of hemoglobin oxygen saturation variations in single vessels in vivo using photoacoustic microscopy,”

Appl. Phys. Lett., 90

(5), 053901

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.2435697 APPLAB 0003-6951 Google Scholar

A. DorrJ. G. SledN. Kabani,

“Three-dimensional cerebral vasculature of the CBA mouse brain: a magnetic resonance imaging and micro computed tomography study,”

Neuroimage, 35

(4), 1409

–1423

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.12.040 NEIMEF 1053-8119 Google Scholar

M. Zhuanget al.,

“Testimony for hypothesis of protective barrier formed by edge-flowing blood in vessel,”

Chin. J. Microcirc., 8

(3), 3

–5

(1998). Google Scholar

L. G. WhitbyJ. AxelrodH. Weil-Malherbe,

“Endocrine classic—the fate of H-3-norepinephrine in animals,”

Endocrinologist, 10

(6), 364

–372

(2000). Google Scholar

L. G. WhitbyJ. AxelrodH. Weil-Malherbe,

“The fate of H3-norepinephrine in animals,”

J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther., 132

(2), 193

–201

(1961). Google Scholar

R. Takahashiet al.,

“The vasocontractive action of norepinephrine and serotonin in deep arterioles of rat cerebral gray matter,”

Tohuko J. Exp. Med., 190

(2), 129

–142

(2000). http://dx.doi.org/10.1620/tjem.190.129 TJEMAO 0040-8727 Google Scholar

M. Wahlet al.,

“Effect of I-norepinephrine on the diameter of pial arterioles and arteries in the cat,”

Circ. Res., 31

(2), 248

–256

(1972). http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/01.RES.31.2.248 CIRUAL 0009-7330 Google Scholar

L. Sokoloff,

“The action of drugs on the cerebral circulation,”

Pharmacol. Rev., 11

(1), 1

–85

(1959). PAREAQ 0031-6997 Google Scholar

E. T. MacKenzieet al.,

“Cerebral circulation and norepinephrine: relevance of the blood-brain barrier,”

Am. J. Physiol., 231

(2), 483

–488

(1976). AJPHAP 0002-9513 Google Scholar

P. BrassardT. SeifertN. H. Secher,

“Is cerebral oxygenation negatively affected by infusion of norepinephrine in healthy subjects?,”

Br. J. Anaesth., 102

(6), 800

–805

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bja/aep065 BJANAD 0007-0912 Google Scholar

A. Y. Bluestoneet al.,

“Three-dimensional optical tomographic brain imaging in small animals, part 2: unilateral carotid occlusion,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 9

(5), 1063

–1073

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.1784472 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

H. Wanget al.,

“Early monitoring of cerebral hypoperfusion in rats by laser speckle imaging and functional photoacoustic microscopy,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 17

(6), 061207

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.17.6.061207 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

S. McCannE. Wise,

“Cardiovascular system,”

Anatomy Coloring Book, Kaplan Publishing, New York

(2008). Google Scholar

A. V. Kurpadet al.,

“Muscle and whole body metabolism after norepinephrine,”

Endocrinol. Metab., 266

(6), 877

–884

(1994). Google Scholar

I. TakayanaqiM. Moriya,

“Alpha 1A-adrenoceptors in rabbit bronchus,”

Eur. J. Pharmacol., 202

(2), 281

–283

(1991). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0014-2999(91)90306-B EJPHAZ 0014-2999 Google Scholar

L. K. BekarH. S. WeiM. Nedergaard,

“The locus coeruleus-norepinephrine network optimizes coupling of cerebral blood volume with oxygen demand,”

J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab., 32

(12), 2134

–2145

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2012.115 JCBMDN 0271-678X Google Scholar

P. B. Joneset al.,

“Simultaneous multispectral reflectance imaging and laser speckle flowmetry of cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism in focal cerebral ischemia,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 13

(4), 044007

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.2950312 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

L. BerntmanN. DahlgrenB. K. Siesjo,

“Influence of intravenously administered catecholamines on cerebral oxygen consumption and blood flow in the rat,”

Acta Physiol. Scand., 104

(1), 101

–108

(1978). http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/apha.1978.104.issue-1 APSCAX 0001-6772 Google Scholar

J. J. Yaoet al.,

“In vivo photoacoustic imaging of transverse blood flow by using Doppler broadening of bandwidth,”

Opt. Lett., 35

(9), 1419

–1421

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.35.001419 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

E. ShivesY. XuH. B. Jiang,

“Fluorescence lifetime tomography of turbid media based on an oxygen-sensitive dye,”

Opt. Express, 10

(26), 1557

–1562

(2002). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.10.001557 OPEXFF 1094-4087 Google Scholar

|