|

|

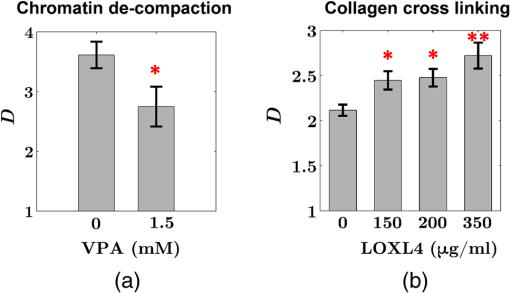

1.IntroductionCancer progression is a multistep process that develops through a number of stages, including dysplasia, tumorigenesis, and metastases. One of the earliest stages is field carcinogenesis (also referred to as field cancerization, field effect, field of injury, field defect, etc.), the concept that a diffuse injury from genetic/environmental stimuli provides a fertile mutational field with focal tumorigenesis occurring via stochastic events such as inactivation of tumor suppressor genes.1,2 The concept of field carcinogenesis is well established in cancer biology and clinical medicine and has been observed in essentially all solid cancers (lung,3 colon and rectum,4,5 prostate,6,7 esophageal,8 pancreatic,9 ovarian, head and neck,10 stomach,11 and breast12). It provides the biological underpinning of the occurrence of both synchronous (multiple tumors in the organ) and metachronous (recurrent neoplasia elsewhere in the organ) lesions. Because field carcinogenesis provides the key to tumor initiation, it has relevance not only for clinical medicine, but also for fundamental cancer biology. During field carcinogenesis, an affected organ typically appears to be grossly and histologically normal under a conventional microscope with no visible macro- or microscopic structural changes. Undetectable by histopathology, however, the initial molecular and ultrastructural alterations have already occurred. (The term “ultrastructure” refers to tissue morphology that is below the resolution of microscopic histopathology and encompasses the suborganelles and macromolecular length scales—typically on the order of several hundreds of nanometers and below and down to a few tens of nanometers.) Because these length scales are unresolvable by a conventional microscope, there is a need to develop other methods to detect such early alterations. A number of optical techniques have been previously reported for studying field carcinogenesis in various cancers. Raman scattering has been developed in combination with classification methods to detect the risk of cervical and skin cancers.13,14 Karyometric analysis was used to assess nuclear chromatin patterns in colorectal cancer (CRC) field carcinogenesis.15 Fourier-domain low-coherence interferometry (fLCI) has been used to investigate the cell nuclear size changes in colon mucosa on a CRC animal model.16 Elastic scattering spectroscopy (ESS) of uninvolved mucosa has been reported to detect the CRC cancer risk.17 Low coherence-enhanced backscattering (LEBS) spectroscopy has also been applied to demonstrate the field carcinogenesis in CRC, pancreatic cancer (PC), and lung cancer ex vivo and in vivo.18–21 Enhanced backscattering (EBS) spectroscopy has been used to study ultrastructural alterations in CRC and PC field effects ex vivo.22 These earlier studies have shown the promise of an optical detection of field carcinogenesis for early cancer screening applications (e.g., LEBS) and diagnosis (e.g., fLCI and ESS). However, a comprehensive analysis of the optical and ultrastructural alterations associated with field carcinogenesis in the two major tissues comprising the mucosa, i.e., the epithelium and stroma [extracellular matrix (ECM) in particular] is still lacking. Here, we use inverse spectroscopic optical coherence tomography (ISOCT)23–26 to provide a quantification of the ultrastructural alterations in epithelium and stroma in field carcinogenesis. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) conventionally has been used to provide the microscopic reconstruction of tissue morphology with a spatial resolution on the order of several microns.27,28 It has also been used to quantify optical properties of bulk tissue including scattering coefficient,29–32 backscattering coefficient,33,34 anisotropy factor,29,35 and absorption coefficient.36,37 The ISOCT models the tissue as a medium with a continuously varying refractive index (RI). By measuring its optical properties, the RI correlation function can be inversely recovered. Because of the linear relationship between RI and macromolecular mass density, ISOCT is then able to quantify the ultrastructural properties underlying the optical properties at each three-dimensional (3-D) OCT voxel of spatial resolution.24 Moreover, because ISOCT utilizes the spectral information to measure the self-interference within a resolution-limited voxel, the length scale of sensitivity of ISOCT can be as small as , far beyond the resolution limit of conventional microscopy.23,38 In this article, we apply ISOCT to address three specific questions about field carcinogenesis: (1) In which mucosal compartment (i.e., epithelium versus ECM) do changes occur? (2) What are the associated ultrastructural alterations that occur within each of these compartments? and (3) What are some of the specific mechanisms that contribute to these ultrastructural alterations? To answer these questions, we studied the optical and ultrastructural changes in CRC field carcinogenesis and separately analyzed the epithelium and stroma compartments. Furthermore, considering that the histological alterations are a universal marker of carcinogenesis in essentially all types of cancer, we tested whether the optical and ultrastructural alterations are specific to CRC field carcinogenesis or could potentially represent a more ubiquitous event pertinent to field carcinogenesis in other organs. Therefore, we studied optical and ultrastructural alterations in PC field carcinogenesis for comparison. Ex vivo biopsies from the rectum and peri-ampullary duodenum (i.e., a portion of the duodenum in close proximity to the opening of the pancreatic duct) were used as the surrogate sites for CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis, respectively. Furthermore, we used in vitro models to investigate whether chromatin clumping and collagen cross-linking, two of the most common hallmarks of structural changes in cancer, could contribute to the ultrastructural alterations in field carcinogenesis. The article is organized as follows: in Sec. 2, we provide an in-depth review of the biological background and significance of the study; in Sec. 3, we introduce the theory of modeling tissue as a continuously varying RI medium and the inverse model for ISOCT; in Sec. 4, the methods of the study are explained; Sec. 5 presents the results; Sec. 6 is the discussion; and Sec. 7 is the conclusion. 2.Biological Background and SignificanceThe terminology of the different stages of carcinogenesis has been introduced by pathologists through either a gross or microscopic (histopathologic) examination of tumors and precancerous lesions. Histopathology has been the gold standard for cancer diagnosis for the past century and will remain so for the foreseeable future, despite an ongoing revolution in our understanding of the molecular underpinnings of the disease. The reason is, to a large extent, because morphological (structural) alterations are a common denominator of essentially all molecular pathways and essentially all cancer types. While there are hundreds of genetic events and more than a dozen of distinct molecular pathways that have been implicated in carcinogenesis in a given organ site, essentially all neoplasms share the same few morphological alterations. The morphological hallmarks of neoplasia include both intracellular and ECM alterations. A key cellular marker is nuclear atypia, in particular abnormal chromatin clumping and hyperchromatism. With regard to ECM events, collagen cross-linking leading to an increase in the ECM stiffness is an ubiquitous event in the tumor microenvironment. The sequence from field carcinogenesis to dysplasia to carcinoma to metastases is driven by the development of molecular as well as morphological alterations at progressively larger length scales. A carcinoma is frequently a macroscopically detectable lesion with morphological alterations at both macro- and microscales. At an earlier stage, dysplasia is a term used to describe a precancerous, early neoplastic process based on the microscopic appearance of cells. While some dysplastic lesions may have macroscopic manifestations (e.g., colon adenomas), the majority are defined exclusively based on their micromorphology (e.g., colon flat dysplasia and cervical dysplasia). In either case, micromorphology is the defining characteristic. At an even earlier stage, field carcinogenesis does not exhibit microscopic abnormalities and the tissue appears histologically normal. At this stage, however, the tissue does possess multiple molecular as well as submicroscopic or ultrastructural alterations. A myriad of molecular alterations in field carcinogenesis has been reported, including biochemical (e.g., protein kinase C activity,39 ornithine decarboxylase,40 and mucus disaccharide content41), immunohistochemical (the loss of cytochrome C oxidase subunit I42), cellular (proliferation43 and apoptosis44), genomic [tumor suppress gene p53,3,10 cyclooxygenase 2, osteopontin,45 the loss of imprinting of insulin growth factor (IGF)-2,46,47 tumor growth factor(TGF)-,48 and IGF binding protein 349], proteomic,50 microvasculature (increased blood supply,51–53 the expression of pro-angiogenic proteins such as COX-2, iNOS, VEGF, and osteopontin, germline vascular polymorphisms such as VEGF and Eng-154), and epigenomic (abnormal methylation55,56 and histone acetylation57,58) markers. Many of these molecular events in field carcinogenesis have ultrastructural consequences. Indeed, ultrastructural, epigenetic, genetic, and other molecular events in carcinogenesis are inherently interdependent. For instance, the altered DNA methylation (an epigenetic event)55 changes the higher-order chromatin structure (an ultrastructural event),59 which in turn affects the gene expression (genetic alterations).56,60 One recent insight into the development of carcinomas is that there is both an epithelial and stromal components. In fact, cross-talk from the stroma is critical for all phases of neoplastic transformation. One essential question on the mechanisms underlying the development of field carcinogenesis is this: In which tissue compartment do the initial molecular/ultrastructural alterations drive field carcinogenesis, epithelium or stroma, or both? One theory is that the genomic and epigenomic alterations in epithelial cells at this premalignant stage drive field carcinogenesis. However, there are emerging data suggesting that the stroma not only reciprocates the epithelial changes, but may also potentiate the epithelial changes in field carcinogenesis.61,62 For example, transgenic mice with transforming growth factor type II receptor knockdown restricted to the stroma still had evidence of malignant transformation of the epithelium.63 While these earlier studies demonstrate the importance of epithelium-stroma cross-talk in cancer, the exact contribution from the two compartments in human field carcinogenesis remains unknown. Given the biological context of field carcinogenesis, the study presented here addresses the ultrastructural changes in the epithelium and stroma separately. 3.Theory3.1.Continuously Varying RI Model for Tissue and Corresponding Optical PropertiesOptical scattering originates from spatial heterogeneity in the RI of biological tissue. To model this heterogeneity, a number of approaches have been proposed. In one popular representation, tissue is treated as a collection of homogeneous spheres (or spheroids) of various sizes (discrete particle model).64,65 The total scattering is then an incoherent summation of the scattered intensity from all spheres. Those models provide reasonably accurate representations for cellular components such as the cell nucleus, mitochondria, and ribosomes, which arguably resemble discrete spheres/spheroids. The shortcomings of the discrete particle model are that the complex inner structure of organelles is neglected, as well as the interaction between scatterers, and the model is not able to accurately represent ECM network structures. In fact, most tissue components are interconnected instead of being isolated and discrete; and within organelles, the inner structures are spatially heterogeneous rather than being homogeneous. An alternative approach is to model tissue as a continuously varying RI medium.66–70 A comprehensive way to quantify such a medium is by using the RI autocorrelation function to calculate the correlation of RI between any two points in 3-D space with a spatial separation . Since the exact RI correlation function of tissue has not yet been accurately measured and may vary significantly among different tissue types, we instead used the versatile three-parameter Whittle–Matèrn (W–M) family of correlation functions to model the spatial distribution of RI in tissue66,70 where is the modified Bessel function of the second type; is the amplitude of the RI fluctuation; is the functional “shape factor” determining the type of the function; and is the length scale of the correlation function whose exact meaning depends on . Table 1 lists the functional type for different values. When , the correlation function is a power law and the tissue is organized as a mass fractal. is then the mass fractal dimension . For , defines the upper length scale of the mass fractal range. For , is an exponential function and is its correlation length, where . The physical meaning of also depends on . A definition of an RI correlation function requires a normalization such that at the origin (), the function is equal to the variance of the RI fluctuation . For , the W–M correlation function approaches infinity at the origin. One way to keep the functional form bounded is to introduce another lower limit of length scale below which the function levels to the origin, as in Eq. (2). The value of could be chosen to be the lower limit of the length scale of sensitivity, since it is no longer sensitive to any structural perturbations smaller than . For , the W–M correlation functions are naturally bounded at the origin, and thus can be analytically associated with .Table 1D dependent functional type.

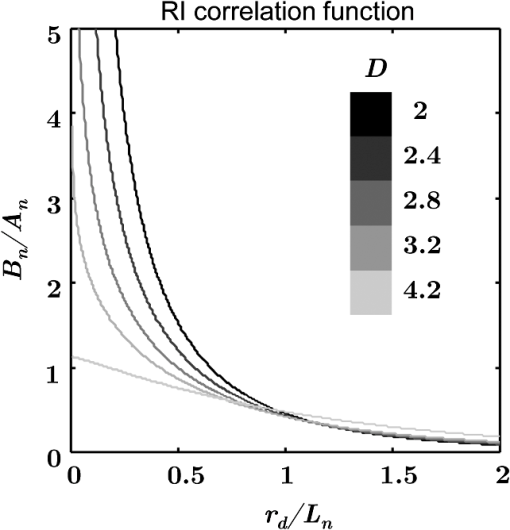

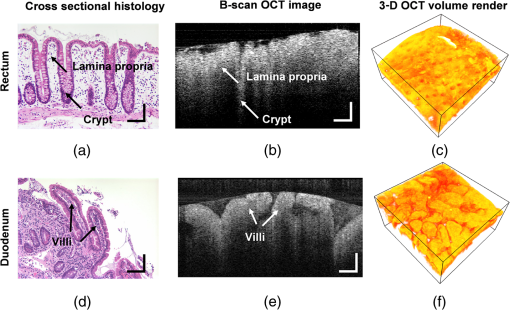

Figure 1 shows the examples of at various values. The shape of becomes flatter in the limit of when increases beyond . Given the linear relationship between RI and local macromolecular mass density defined by the Gladstone–Dale equation,71,72 quantification of the RI correlation function is actually a measure of the tissue structure where is the local concentration of the solid material (e.g., macromolecules), and is the RI increment, usually equals to for biological materials. is the RI of water. Thus, is not only a tissue RI correlation function, but it is also proportional to the correlation function of the spatial distribution of macromolecular densityis the most fundamental statistical measure of tissue ultrastructure. Accordingly, in this article, we refer to an alteration in tissue ultrastructure as a change in its at the ultrastructural length scale. With a defined , the differential scattering cross-section per unit volume can be obtained by a Fourier transform under the first-order Born approximation66 where is the gamma function, is the wave number, and is the polar and azimuthal angles of the scattering direction. Thus translates into a measurable optical quantity, which in turn makes it possible to invert the measurements back to the structural properties. The condition for the Born approximation to be valid is73Optical properties are defined through . The scattering coefficient is obtained as the integral of over the entire angular space The anisotropy factor is the average cosine of the scattering angle of The reduced scattering coefficient is defined as The backscattering coefficient is defined as All the above optical properties can be analytically expressed in terms of three parameters defining the RI correlation function,66 which establishes the forward problem for the following inverse calculation. In biological tissue, the anisotropy factor is typically larger than 0.7 which implies . In this regime, both and are proportional to . In the case of , this proportionality is only valid for . When , is no longer dependent on wavelength. In the case of , there is no such limit. The conditioned functions of and are24,66 The above two expressions are particularly useful because can be measured in the diffused light regime by technique such as diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS),74,75 and can be measured in the ballistic region by technique such as reflectance confocal microscopy76 or OCT.27 Note that the above expressions of and are limited forms when . It is more accurate to use the complete analytical equations (see Refs. 24 and 57). 3.2.ISOCTThe OCT primarily detects the backscattering signal from tissue. By interfering the scattered field with a reference field, OCT generates the depth-resolved tomographic images of the scattering medium. The principle of ISOCT is that the interference of light scattered from the spatial variations of RI (e.g., tissue ultrastructures) within a 3-D resolution voxel results in detectable optical signals, which in turn can be used to inversely calculate the ultrastructural properties. By measuring the spectra of two fundamental optical parameters ( and ) for each voxel, the three structural parameters ( or , , and ) can be calculated according to the analytical expression [Eqs. (5)–(11)] introduced in Sec. 3.1. We can take a first-order approximation and model the OCT A-line signal as24 where is the illumination intensity, is the reflectance on the reference arm, is the temporal coherence length of the source, and is the geometric penetration depth in tissue. Note that is proportional to the optical depth () by a scaling factor of , , where is the mean RI of the medium (assumed to be 1.38 for biological tissue). The intensity decay rate along the depth is proportional to . The depth-resolved is equal toIn addition, the wavelength-dependent can be obtained by a time-frequency analysis method on the OCT interferogram such as short-time Fourier transform (STFT).77,78 Thus, the spectrum of can be calculated. This inverse method directly measures the spectra of two fundamental optical quantities: , and , and indirectly deduces the values of , , or , and . According to Eq. (11), the exponent of spectra is equal to , so that can be calculated by fitting the spectra with a power law function of . Then, is a function of and the ratio of and , , and can be calculated according to an equation in Ref. 24. or can be calculated based on Eqs. (2) and (11). The value of is a function of and and can be calculated according to the same equation reported previously.66,70 The data-processing method is described in detail in Sec. 4.3. 4.Methods4.1.OCT System SetupTo implement the ISOCT imaging system, we adopted an open-space Fourier-domain OCT (FDOCT) configuration with an illumination wavelength ranging from 650 to 800 nm (SuperK, NKT Photonics, Birkerød, Denmark). The laser was delivered by an optical fiber, collimated by a lens, and input into a cube beam splitter (Thorlabs, CM1-BS013, Newton, New Jersey) by which the light was divided into a sample arm and a reference arm. The reference arm consisted of a series of glass plates for dispersion control, and a mirror reflecting the light backward. The sample arm consisted of a two-dimensional (2-D) scanning mirror (Thorlabs, GVSM002, Newton, New Jersey) and an objective lens (effective ) to focus the light onto a specimen. The scanning range is in the transverse plane and each direction has 256 A-lines. We used a 2048 pixel line-scan camera (Aviiva, SM2, e2v, Milpitas, California) in a homemade spectrometer to capture the interference spectrum. The axial resolution was measured as in air and the transverse resolution was estimated to be . The depth of imaging was in tissue. 4.2.Image SegmentationThe OCT provided the 3-D volumetric images of tissue. In order to study the depth-resolved optical and ultrastructural properties from epithelium and stroma separately, we digitally delineated the surface of the tissue and segmented the crypts (composed of epithelial cells) and stroma from OCT images of colonic mucosa. The topical surface of the 3-D volumetric image of colonic mucosa was identified by the intensity gradient along the A-line signal. A threshold at 20% of the maximum intensity of a B-scan image was selected to binarize the image. The derivative of the binarized A-line was taken, and the peak locations marked the boundaries. In order to exclude the mucus and cell debris on top of the tissue surface, an iterative algorithm was designed as follows: after a boundary was detected, the average value of the next 30 pixels was calculated on the binarized A-line. If the averaged value was larger than 0.9 (averaged from the binarized signal), then the boundary location was recorded; otherwise, it was discarded. Then, the algorithm moved to the next boundary until the condition was met. This procedure was repeated on the B-scans, and thus the tissue surface was identified. The segmentation of crypts and stroma in rectal mucosa was based on the intensity thresholding. We first created a 2-D grayscale image using the mean intensity projection along a depth of to 350 μm from the surface. An intensity histogram adjustment was then performed to maximize the contrast. Next, a global image threshold calculated using Otsu’s methods79 was used to binarize the image. Closed areas smaller than were removed as noise, and the perimeters of the closed areas were marked as the boundaries between the crypts and stroma. Finally, a rectangular region of interest (ROI) on the 2-D mean intensity projection image was manually selected based on visual confirmation of whether cryptal or stromal components could be separated by our segmentation algorithm. Within the ROI, the crypts and stroma were then digitally segmented for ISOCT analysis. 4.3.ISOCT Signal ProcessingIn order to calculate the optical (,, and ) and ultrastructural (, , and ) properties, we performed ISOCT signal processing on the raw FDOCT interference spectrum. The A-line signal with respect to the optical path was first obtained by a Fourier transform on the entire bandwidth of the interference spectrum. The optical path was then converted into geometric penetration depth by using the mean RI of the medium ( in tissue). Next, the natural log of the A-line signal was fitted with a linear function of . The slope is proportional to according to Eq. (13), and thus we calculated from the fitted slope. Next, the depth-resolved backscattering coefficient was obtained by multiplying to the square intensity of the A-line signal according to Eq. (14). To calibrate the measurements of and , microsphere aqueous phantoms with different microsphere diameters were prepared and imaged. The squared A-line intensity and the fitted slope were calibrated to and , which were predicted by Mie theory. The calibration data have been presented in our previous publication.24 Next, we calculated using the following steps. A Gaussian spectral window with width was applied to the interference spectrum, and the A-line signal contributed by the selected band was obtained by a Fourier transform. The depth resolution was relaxed to due to the windowing. The corresponding was obtained by the same method described above. This process was repeated with the Gaussian window sweeping through the whole spectral range, and thus the wavelength-dependent was generated. Then, a power law function of was fitted to the spectra of . The exponent is equal to according to Eq. (11), and thus we calculated the value of from the fitted exponent. Next, we deduced . The ratio of and , , was calculated. The value of depends on and , and thus we obtained with known and according to the equation as seen in the previous publication.24 Finally, was calculated with and according to the same equation as in Refs. 66 and 70. Then, was calculated according to Eq. (11) with known , , and , where is taken at the central wavelength 710 nm. 4.4.Ex Vivo Specimen PreparationHuman ex vivo biopsies were obtained by following the protocol approved by NorthShore University Health System’s Institutional Review Board, and all patients who provided samples gave informed consent. The normal-appearing rectal endoscopic biopsies were acquired during colonoscopies. If colonic polyps were found during the colonoscopy, then the polyps were retrieved for histopathological diagnosis. The ISOCT measurements were taken on the rectal biopsies. The duodenal biopsies were acquired from the peri-ampullary mucosa (1 to 3 cm from the ampulla) either during upper endoscopy procedures or from surgically resected Whipple specimens within 30 min of the Whipple procedure. Immediately after removal, the specimens were transferred to a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution and refrigerated until measurement with ISOCT. 4.5.Cell Preparation and HDAC Inhibition by VPATo introduce cell chromatin structural changes, we adapted an established in vitro model using valproic acid (VPA) to inhibit the DNA-histone binding, partly mediated by histone deacetylase (HDACs). HT-29 colon cancer cell lines were grown in McCoy’s 5A medium (ATCC, Manassas, Virginia) mixed with 10% fetal bovine serum penicillin/streptomycin in a 5% environment at 37°C. C-terminus Src kinase (CSK) shRNA-stably transfected HT-29 cells (CSK knockdown) were obtained and grown as previously described.80 The CSK knockdown cells were treated with VPA (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) at a concentration of 1.5 mM for 4 h according to the protocol of previous publications.81 For ISOCT measurements, cells were trypsinized from the culture dish and pelleted at 1000 rpm for 5 min in a centrifuge and transferred onto a glass slide for imaging. We estimated around 10 million cells to form a pellet. The thickness of the cell pellets was several hundred of microns, so that the reflection from the glass slide can be excluded in the STFT analysis. All measurements were completed within 15 min of trypsinization to ensure the cell viability. 4.6.Collagen Gel Preparation and Cross-linkingTo mimic the collagen fiber network and to introduce ECM structural changes, we used a collagen in vitro model. Preparation of lysyl oxidase (LOX)-containing gels was adapted from a previously described protocol.82 A collagen solution was prepared by mixing rat tail Collagen I (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California) with deionized water, PBS (Sigma, dilution), and 1-M NaOH (Sigma, dilution) on ice. LOXL4 (Sigma) was added to the collagen to reach final concentrations of 0, 150, 200, or , and 50 μL of each solution was placed in a 16-well glass chamber slide (Thermo Scientific, Hanover Park, Illinois). Gels were incubated at 37°C for 1 h, after which 175 μL of PBS was added to the top of each gel. The gels were incubated at 37°C for 5 days. Before OCT imaging, the supernatant PBS was removed by a pipette. Then, the gel was imaged from the glass chamber slide to avoid the unnecessary disturbance. 4.7.StatisticsAll statistical data were plotted as . One-tailed, two-sample Student’s t-tests were used to analyze the significance of the difference in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis. A one-tailed t-test was used, since the directionality of the changes in optical and ultrastructural properties was established in a previous study.22 5.ResultsIn this section, we first compare the OCT images with the histology from rectal and duodenum samples (Sec. 5.1). Next, we present the 3-D segmentation results from rectal OCT images to separate epithelium and stroma (Sec. 5.2). We then present the ISOCT analysis on the optical and ultrastructural changes in these two tissue compartments in CRC field carcinogenesis (Secs. 5.3 and 5.4) as compared with PC field carcinogenesis (Sec. 5.5). Lastly, we present two in vitro experiments to confirm some of the mechanisms of the observed changes in cellular and extracellular components (Sec. 5.6). 5.1.OCT Microscopic Representation for Rectal and Duodenal SpecimensFigure 2 shows a comparison between the H&E-stained histological pictures and the OCT images from ex vivo rectal and duodenal specimens. The structure of colonic mucosa consists of a folded epithelial cell layer (crypts) surrounded by the stroma [lamina propria (LP)], as shown in Fig. 2(a). The colonic epithelial cells divide and proliferate from the base of the crypts and migrate to the cryptal apex until shedding into the colonic lumen. As we can see in Fig. 2(a), the epithelial cells at the base of the crypts have smaller sizes and pack more densely than the upper portion of the crypts. The top of the LP is covered by a single layer of matured epithelial cells around 20 to 30-μm thick, and some of the shedded cell debris can be observed. In LP, the primary component is a complex collagen network forming the ECM, within which there are also scattered stromal cells. Figure 2(b) shows the corresponding cross-sectional B-scan OCT image. The crypts can be seen as extending into the mucosa, and the LP can be seen as the surrounding tissue. A 3-D intensity rendering of a rectal sample is shown in Fig. 2(c). Fig. 2H&E histology, OCT B-scan images, and three-dimensional (3-D) OCT volume render for (a–c) rectal and (d–f) duodenal biopsies. .  A similar comparison for the duodenal specimen is shown in Figs. 2(d)–2(f). In the duodenum, the most prominent morphological features are the villi shown in Fig. 2(d). The villi consist of an outer shell of epithelial cells with LP filling the inside. The diameter of a villus is around 200 to 300 μm and the length can be as long as . From the OCT B-scan and 3-D images in Figs. 2(e) and 2(f), the randomly oriented villi structures were visualized. Using the comparison with histology, we confirmed that the OCT images acquired from rectal and duodenal specimens accurately measured the expected microscopic structures. 5.2.Three-Dimensional Segmentation of Epithelium and LPBecause the OCT images can accurately reconstruct the tissue microscopic features, we developed image segmentation methods to separate epithelial and LP components in rectal biopsies for later ISOCT analysis. As Fig. 3(a) shows, the tissue surface was detected using the intensity thresholding method described in Sec. 3.2. The red line in the B-scan image delineates the tissue boundary and defines the origin of the penetration depth . Thus, the penetration depth is the absolute depth with respect to the surface. We could also see that in deeper portions of the mucosa, the epithelium had a higher signal than LP, which creates contrast for a separation of the two compartments. Figures 3(b)–3(d) illustrates the segmentation method. We approximated epithelial structures as cylinders and took mean intensity projection from a slab of the volumetric data. We found that for depths between around , the contrast between epithelium and LP was optimal. Figure 3(d) shows an example of the mean intensity projection map from to 0.35-mm slab. Using a ROI exampled in the yellow square of Fig. 3(d), we applied our segmentation algorithm to separate the two tissue components as in Fig. 3(e) for further ISOCT analysis. The segmentation method is described in Sec. 3.2. With volumetric image processing, we can separate epithelium and LP in 3-D spaces and analyze their depth-resolved properties separately. Fig. 3Localization of epithelium (Epi) and lamina propria (LP) in 3-D spaces. (a) Tissue surface is identified and defined at ; the origin of the penetration depth is from the tissue surface; one A-line signal is plotted to show the intensity change along the depth. (b–d) Mean intensity projection from slabs between different penetration depths. . (e) Crypt segmentation from the ROI in (d). Epi and LP identified with blue and green asterisks.  5.3.Optical and Ultrastructural Changes in Epithelium and LP in CRC Field CarcinogenesisWith 3-D imaging capability and image segmentation, we performed ISOCT analysis to quantitatively compare the changes in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis. We first investigated CRC field carcinogenesis on rectal biopsies. The CRC field carcinogenesis occurs in all segments of the colon, including the ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoidal colon, and the rectum. Thus, we targeted the rectum as the surrogate site for the CRC field carcinogenesis because this region is the most accessible for CRC screening in the clinic. According to the colonoscopic findings and histopathological examination of retrieved colonic polyps, the patients were categorized into four groups as shown in Table 2: patients without any polyps present during colonoscopy (control group); patients with hyperplastic polyps (HPs), which are generally benign; patients harboring adenomatous (premalignant) polyps with polyp diameter less than or equal to 9 mm (adenoma); and patients harboring adenomatous polyps with polyp diameter greater than or equal to 10 mm [advanced adenomas (AA)]. It is important to note that not all adenomas progress to cancer, but the risk of progression increases with adenoma size. Thus, adenomas are a biomarker of future CRC, and the risk progresses from control patients to those with adenoma and AA. Table 2CRC study: patient characteristics.

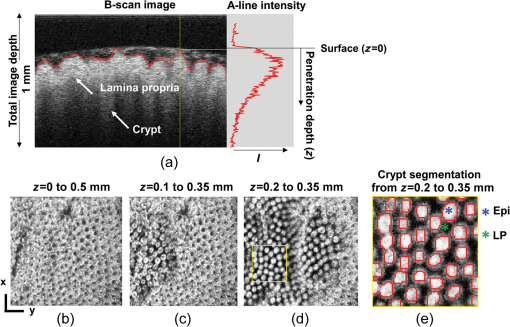

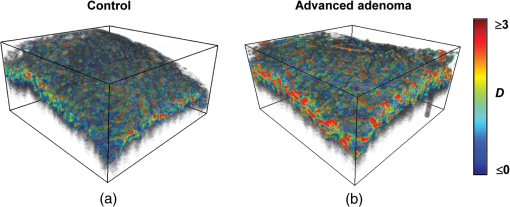

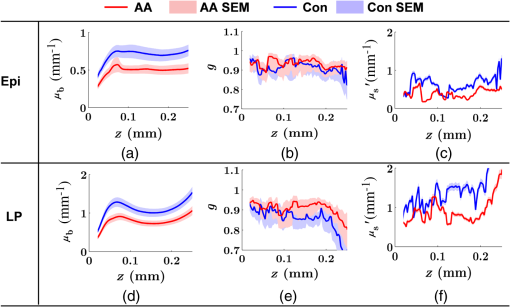

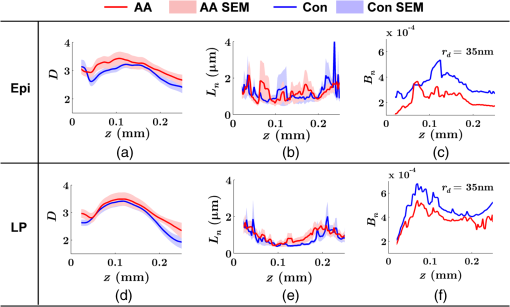

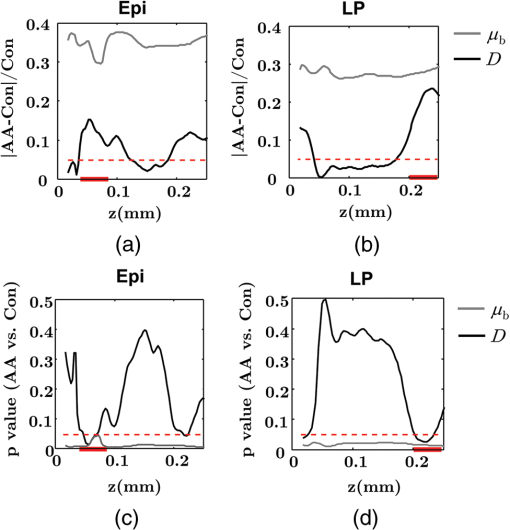

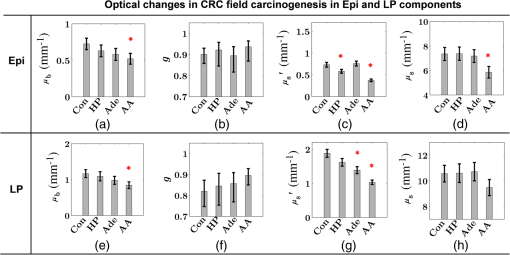

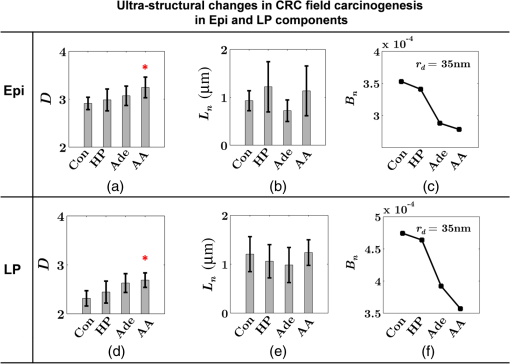

Note: HP hyperplastic polyp; AA advanced adenoma. Using our segmentation methods discussed previously, we segmented 71 of the 85 patient biopsies: , , , and . Other samples were deformed so that the epithelium and LP were unrecognizable from the image, possibly due to the mechanical stress during the pinch biopsy processing. Those samples were excluded from the following analysis. The advantage of ISOCT in quantifying 3-D ultrastructural properties is illustrated in Fig. 4. Two representative examples of 3-D images from rectal biopsies in control and AA groups were pseudocolor coded by . Qualitative comparison between rectal mucosae from AA and control patients [Fig. 4(a)] shows that the AA samples have an overall higher . We could also see that there was a significant heterogeneity in the spatial distribution of across the mucosa. To yield a more robust statistical analysis, we separately averaged the A-line signal from all crypts and LP within an ROI [see the definition in Sec. 4.2 and the example in Fig. 3(d)] and calculated and for the two tissue components. For each patient, the mean values of each parameter from several ROIs () were taken. The image segmentation then allowed us to examine the depth-dependent changes in epithelium and LP in CRC field carcinogenesis. Fig. 4Pseudocolor 3-D images encoded by from representative rectal biopsies in (a) control and (b) advanced adenoma (AA) groups. The volume rendering intensity maps in grayscale are fused with the corresponding color-coded map. The 3-D map is obtained after smoothing by 3-D median filter in . Dimension: in .  Figure 5 shows the comparison between control and AA groups in both epithelium and LP compartments. Note again that the -axis represents the penetration depth with respect to the surface. Epithelium and LP showed lower in the AA group than in the control [Figs. 5(a) and 5(d)]. at first increased to a local maximum of about , roughly at the depth of the basal membrane, but maintained a roughly constant value in deeper tissue. was higher for AA in both epithelium and LP [Figs. 5(b) and 5(e)]. The separation was particularly dramatic in LP at depths greater than 100 μm. [Figs. 5(c) and 5(f)] was smaller for the AA group in both epithelium and LP. Fig. 5Depth-resolved optical properties quantified in colorectal cancer (CRC) field carcinogenesis. The parameters were compared between control (Con) and AA groups separately in (a–c) epithelium (Epi) and (d–f) LP. The shadow areas show the standard error of the mean (SEM). The averaged values were used for calculation, and the SEM of is calculated from measurements.  Next, we examined the ultrastructural changes quantified based on the W–M model. Both epithelium and LP from AA patients showed a higher compared with that of control patients [Figs. 6(a) and 6(d)]. Epithelium showed a better contrast within the top 100-μm depth, whereas in LP, the greatest change was noted in deeper tissue [Figs. 6(a) and 6(d)]. did not appear to be appreciably different in epithelium between control and AA, but in LP, AA patients had elevated for tissue depths around 100 to 200 μm. To compare the RI fluctuation magnitude, Figs. 6(c) and 6(f) show () as a function of tissue depth. The value of 35 nm is the lower limit of length scale sensitivity of ISOCT, beyond which ISOCT can no longer detect ultrastructural alterations.23 We note that at , the RI fluctuations are weaker in AA group than in control [Figs. 6(c) and 6(f)]. Fig. 6Depth-resolved ultrastructural properties quantified in CRC field carcinogenesis. The parameters were compared between control (Con) and AA groups separately in (a–c) epithelium (Epi) and (d–f) LP. The shadow areas show the standard error of the mean (SEM). is calculated at by using the mean value of , , and according to Eq. (1).  5.4.Depth-Resolved Changes in CRC Field CarcinogenesisThe most significant optical and ultrastructural alterations in the epithelium and LP may occur at different depths. To identify the locations of the alterations in the epithelium and LP, we plotted the relative change in the optical and ultrastructural properties between AA to control groups and the corresponding -values as a function of depth (Fig. 7). Because and are two directly measured depth-resolved quantities, we used them as our representative markers. In epithelium, the contrast for reached a maximum around in depth [Fig. 7(a)], and the depth range, where the difference was significant (), was from 50 to 75 μm [Fig. 7(c)]. In LP, the optimal contrast for was from to 250 μm [Figs. 7(b) and 7(d)]. The -values for are below 0.05 for all depths in both compartments. Fig. 7Percent change and -values of and from AA group to control (Con) group, in (a and c) epithelium (Epi) and (b and d) LP. The dashed lines are labeled 5% level. The red bars on -axis show the depth range where the averaged values are calculated for comparison in Figs. 8 and 9.  Having identified the location of the most significant alterations, we next examined whether the alterations parallel the progression of the severity of field carcinogenesis and the risk of carcinogenesis. As discussed in Sec. 4, we considered four groups of patients depending on colonoscopic findings: patients with no neoplastic lesions, patients with HPs (most carrying no malignant potential), patients with non-AAs, and finally those with AAs. Figure 8 shows the averaged values of the optical properties from 40 to 90-μm depth in epithelium and 200 to 250 μm in LP. Overall, the change in most of the optical properties paralleled the CRC risk from control patients to those with AAs and was consistent in both epithelium and LP: progressively decreased, increased, and decreased. While the change in the majority of the parameters reached statistical significance, a few parameters failed to reach significance level (Fig. 8). This could be due to the biological variability with our finite sample size. Fig. 8Bar plots of optical properties in CRC field carcinogenesis. The averaged (a and e), (b and f), (c and g), and (d and h) were compared in four groups: control (Con), hyperplastic polyps (HPs); adenoma (Ade); and AA. Data were averaged at depth 40 to 90 μm in epithelium (Epi) and 200 to 250 μm in LP. *.  Figure 9 plots the average values of the ultrastructural properties , , and () assessed from the same locations as in Fig. 8. Both in epithelium and LP, increased and () decreased progressively paralleling the risk of CRC from control patients to those with AA. There were no obvious trends for . The values of were around 1 μm. Fig. 9Ultrastructural properties in CRC field carcinogenesis. The averaged (a and d), (b and e), and () (c and f) were compared in four groups: control (Con), HPs; adenoma (Ade); and AA. Data were averaged at depth 40 to 90 μm in epithelium (Epi) and 200 to 250 μm in LP as marked in Fig. 7. *.  5.5.Optical and Ultrastructural Properties in PC Field CarcinogenesisA similar approach and data analysis were used to analyze the optical and ultrastructural alterations occurring in PC field carcinogenesis. While the pancreatic duct shows the diffuse carcinogenesis, directly instrumenting the pancreatic duct is fraught with complications. Several groups have shown that the peri-ampullary duodenum shares profound molecular changes (mutations/methylation) with the pancreatic duct in patients harboring PC.83,84 Thus, we chose the peri-ampullary duodenum as the surrogate site for PC field carcinogenesis. The patients were categorized into two groups as shown in Table 3: control (no pancreatic neoplasia) and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (AC) according to the pathology report after the endoscopic examination. Table 3PC study: patient characteristics.

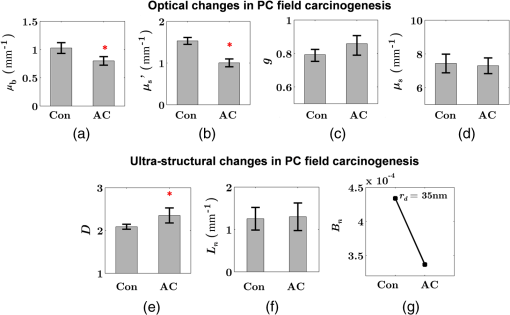

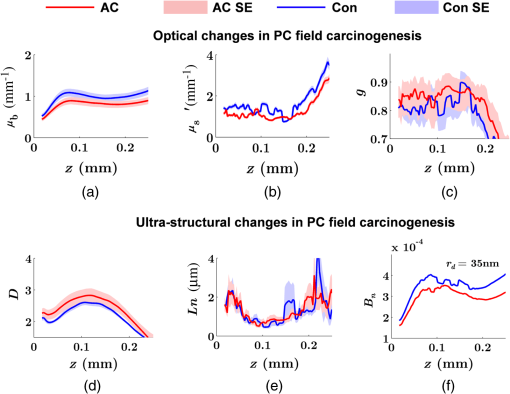

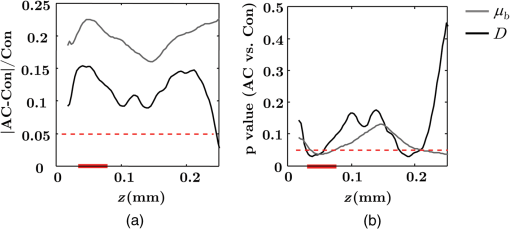

Note: AC adenocarcinoma. Because the structure of duodenal villi is considerably more complicated than the cryptal morphology of rectal mucosa, the separation of epithelium and LP in the duodenal biopsies was impractical. Thus, we calculated the optical and ultrastructural properties of the duodenal biopsies as a combined effect of both components. Depth-resolved optical and ultrastructural changes from PC to control patients were plotted in Fig. 10. Using the similar method in CRC field carcinogenesis, we also identified significant alterations at two depth segments at about 30 to 80 μm and 170 to 220 μm in PC patients based on the changes in and (Fig. 11). The averaged values of the optical and ultrastructural properties from the first segment are plotted in Fig. 12. A decrease in , , and () and increase in and were observed in PC field carcinogenesis, which is consistent with the similar changes in CRC field carcinogenesis. Fig. 10Depth-resolved optical and physical properties of duodenum samples in pancreatic cancer (PC) field carcinogenesis. Comparison of control (Con) group and adenocarcinoma (AC) group for , , and (a–c) and , , and () (d–f). The shadow areas show the standard errors of the mean (SEM).  Fig. 11(a) Relative changes and (b) -values of and from adenocarcinoma (AC) group to control (Con) group in duodenal specimen. The dashed lines are labeled 5% line. The red bars on -axis show the depth range where the averaged values are calculated for comparison in Fig. 12.  5.6.Mechanisms for Intracellular and Extracellular Ultrastructural ChangesIn the previous sections, we investigated the histological location (epithelium versus LP and depth) and physical nature [] of the optical/ultrastructural changes in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis. The next question is what causes these physical changes in terms of specific intra- and extracellular structures? As mentioned above, chromatin clumping and collagen cross-linking are two of the most common structural hallmarks in cancer. Both events are expected to lead to a shift of structural length scales to larger sizes in accordance with the change in observed by ISOCT. Therefore, we tested whether those events could also play a role in the ultrastructural alterations in field carcinogenesis. To alter the chromatin structure, we chose an aggressive variant of colon cancer cell line, CSK knockdown HT-29 cells, applied VPA to inhibit HDACs, and introduced chromatin relaxation. Chromatin compaction is partly mediated by HDACs,85 a class of enzyme that allows the DNA to wrap around the histones. VPA is a drug known to have the effect of inhibiting HDACs, so that the VPA-retreated chromatin is less compacted.81 The treatment was performed according to the established protocol with VPA concentration of 1.5 mM, as described in Sec. 4.5. The ISOCT measurements were performed on cell pellets (cell deposition after centrifuge) after 4-h treatment ( for both 0 and 1.5 mM VPA treatments), at which time point the effect of VPA approximately reached its maximum.86 Figure 13(a) shows a decrease in for cells treated with VPA. This suggests that the chromatin compaction manifests itself as an increase in , in agreement with the field carcinogenesis alteration observed by ISOCT in the rectal epithelium. Fig. 13changes induced by (a) the de-compaction of chromatin structure and (b) the cross-linking of the collagen fiber network. Valproic acid (VPA) was used to inhibit histone deacetylases (HDACs) to relax chromatin. Lysyl oxidase (LOX4) was used to induce cross-linking of the collagen fibers. analysis was performed on the signal averaged within the top 80 μm of the samples. *, **.  To introduce changes in ECM, we used collagen fiber models of ECM and applied LOX to induce the collagen cross-linking. LOX alters collagen structure by promoting collagen cross-linking.82 The gels were incubated with LOXL4 with increasing final concentration from 150 to . As in Fig. 13(b), increased progressively from in control gels to in gels treated with LOXL4 ( for each treatment concentration). This experiment demonstrated that ECM collagen cross-linking induces an increase in in agreement with the field carcinogenesis alteration observed by ISOCT in rectal stroma. 6.DiscussionIn this article, we used ISOCT to study epithelial and stromal alterations in CRC as well as PC fields carcinogenesis. The ISOCT directly measures the spectra of two fundamental optical quantities, and , from which the 3-D distribution of the ultrastructural parameters , , and or are inversely calculated by modeling the autocorrelation function of the spatial distribution of RI in tissue using W–M family of functions. Furthermore, ISOCT can detect nanoscale alterations as small as 35 nm despite the typical microscale resolution of OCT by taking advantage of the significant contribution of subdiffractional length scales to the spectral behavior of .23 These properties make ISOCT well suited to detect the histologically unresolvable ultrastructural alterations in field carcinogenesis and to map the locations of these changes (e.g., epithelium versus stroma). Thus, we employed ISOCT to identify the ultrastructural alterations within the epithelium and stroma in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis and to investigate the potential biological mechanisms responsible for these alterations. We observed that the optical and ultrastructural alterations were present in both the epithelium and stroma in CRC field carcinogenesis. The depth locations of the most significant changes in these two compartments were different. In the epithelium, the most significant increase in and was observed at superficial depths less than 100 μm. Epithelial cells divide and proliferate from the base of the crypt ( deep) and migrate toward the lumen surface as they mature. Our data suggest that the mature epithelial cells located at superficial depths exhibit the most significant optical and ultrastructural changes. In the LP, the most significant changes in and were observed at the depth range from 200 to 250 μm. In addition to quantifying , , and or , we compared the measured RI correlation functional forms from control and precancerous (field carcinogenesis) samples. This comparison illustrates the length scales of the ultrastructural alterations in field carcinogenesis. The overall shape of was consistently “flatter” for field carcinogenesis of both CRC and PC corresponding to a shift of length-scale distributions to larger sizes, as shown in Fig. 14. This is expected in random media with a higher-shape factor , as we observed in our study. Importantly, the differences were mostly apparent at structural length scales smaller than (roughly the length scale of ). Above 0.8 μm, for control and precancerous tissues was similar. This cutoff length scale is close to the resolution of conventional microscopy, which, in theory, is diffraction limited at , but in practice often closer to 1 μm due to light scattering within a histological section. This explains why in field carcinogenesis mucosa appears to be normal based on the criteria of microscopic histopathology (i.e., no microscopic alterations) despite the fact that it possesses ultrastructural alterations. On the other hand, ISOCT can be sensitive to the shape of a RI correlation function for length scales between and 450 nm,23 beyond the resolution limit of conventional microscopes. At such small length scales, microscopy cannot resolve the deterministic structural features, though changes in the statistics of the RI correlation function can still be detected by ISOCT. Fig. 14Functional forms of quantified in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis. (a and b) The RI correlation functional form in epithelium (Epi) and LP from control (Con) and AA groups, respectively and (c) from control (Con) and adenocarcinoma (AC) groups. The functional forms were calculated according to Eq. (1) over the plotted length scale without leveling or truncation. The resolution limit of a conventional microscope (estimated at 350 nm with , 600-nm illumination), and the sensitive length scale of ISOCT were also labeled.  Because ultimately determines the optical properties, the consistent changes of in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis should result in similar changes in the optical properties. Table 4 compares the trends in how optical and ultrastructural properties change in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis. Indeed, in both CRC and PC, the ultrastructural alterations were consistent: a higher and lower (). The optical changes were also consistent with a lower and and higher . This suggests that despite differences in molecular pathways, ultrastructural alterations are a common denominator of field carcinogenesis in different organ sites. Moreover, the changes observed by ISOCT are consistent with the previous ex vivo bench top19,87 and in vivo LEBS probe system.20,21 The lower and higher correspond to the LEBS enhancement factor and spectral slope SS marker. The shapes of RI correlation functions in Fig. 14 are also similar to previous EBS studies in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis.22 It should be noted that although different optical techniques were applied to study the field carcinogenesis in these studies, the trends in the observed alterations of optical properties were found to be the same. Table 4Comparison of changes observed in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis.

Note: I increased; De Decreased; *p<0.05. Having elucidated the physical nature of the ultrastructural alterations in CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis (i.e., a shift of length-scale distribution to larger sizes quantified by higher ), we used in vitro models to confirm that the chromatin compaction and collagen fiber cross-linking could cause to increase in the epithelium and stroma, respectively. These results suggest that the changes known to occur at the dysplasia-to-neoplasia stages of carcinogenesis, i.e., chromatin clumping and ECM cross-linking, may develop considerably earlier in field carcinogenesis, albeit at a smaller, subdiffractional length scales, which may in part explain the increase in observed in epithelium and LP in CRC field effect. The molecular mechanisms underlying the chromatin clumping include, most likely along with other pathways, HDACs upregulation. The in vitro data presented here are further supported by our recent study, which showed that the HDACs are upregulated in CRC field carcinogenesis and confirmed the associated chromatin compaction in epithelial cells in CRC field carcinogenesis.57,58 The molecular mechanisms of ECM changes in field carcinogenesis still require further investigation but may potentially include pathways similar to those responsible for collagen cross-linking in tumor microenvironment such as LOX upregulation. 7.ConclusionWe observed the ultrastructural and optical changes in both epithelial cells and stroma in CRC field carcinogenesis. The epithelial and stromal alterations were consistent, although the most dramatic changes occurred at different depths within the mucosa. Optical changes in field carcinogenesis included a reduction in backscattering coefficient , a lower reduced scattering coefficient , and higher anisotropy factor . Corresponding ultrastructural alterations included a change in the shape of RI correlation function: lower RI fluctuation and higher shape factor of mass density correlation function. Furthermore, the alterations observed in both CRC and PC fields carcinogenesis were consistent and also consistent with previous ex vivo and in vivo studies using other optical techniques (e.g., LEBS and EBS). The ultrastructural alterations, in particular an increase in , could be due, at least in part, to nanoscale manifestations of two classical microscopic events in carcinogenesis: chromatin clumping in epithelial cells and collagen cross-linking in stroma. Both these caused an increase in in in vitro models. Future studies will have to elucidate the molecular causes and consequences of these events and their role in carcinogenesis. AcknowledgmentsThe authors would like to acknowledge the grant support from both the National Institutes of Health (R01CA128641, R01CA165309, and R01CA156186) and the National Science Foundation (CBET-1240416). A. J. Radosevich is supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-0824162. The author also would like to thank Benjamin Keane and Andrew Gomes for their help on the manuscript editing. ReferencesH. ChaiR. E. Brown,

“Field effect in cancer–an update,”

Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci., 39

(4), 331

–337

(2009). ACLSCP 0091-7370 Google Scholar

D. P. SlaughterH. W. SouthwickW. Smejkal,

“Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin,”

Cancer, 6

(5), 963

–968

(1953). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142 60IXAH 0008-543X Google Scholar

W. A. Franklinet al.,

“Widely dispersed p53 mutation in respiratory epithelium. A novel mechanism for field carcinogenesis,”

J. Clin. Invest., 100

(8), 2133

–2137

(1997). http://dx.doi.org/10.1172/JCI119748 JCINAO 0021-9738 Google Scholar

L. Shenet al.,

“MGMT promoter methylation and field defect in sporadic colorectal cancer,”

J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 97

(18), 1330

–1338

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dji275 JNCIEQ 0027-8874 Google Scholar

H. Suzukiet al.,

“Epigenetic inactivation of SFRP genes allows constitutive WNT signaling in colorectal cancer,”

Nat. Genet., 36

(4), 417

–422

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ng1330 NGENEC 1061-4036 Google Scholar

J. Mehrotraet al.,

“Quantitative, spatial resolution of the epigenetic field effect in prostate cancer,”

Prostate, 68

(2), 152

–160

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0045 PRSTDS 1097-0045 Google Scholar

L. NonnV. AnanthanarayananP. H. Gann,

“Evidence for field cancerization of the prostate,”

Prostate, 69

(13), 1470

–1479

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pros.v69:13 PRSTDS 1097-0045 Google Scholar

L. J. Prevoet al.,

“p53-mutant clones and field effects in Barrett’s esophagus,”

Cancer Res., 59

(19), 4784

–4787

(1999). CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

G. Dakuboet al.,

“Clinical implications and utility of field cancerization,”

Cancer Cell Int., 7

(1), 1

–12

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1475-2867-7-2 CCIACC 1475-2867 Google Scholar

B. J. M. Braakhuiset al.,

“A genetic explanation of Slaughter’s concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications,”

Cancer Res., 63

(8), 1727

–1730

(2003). CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

M. Endohet al.,

“RASSF2, a potential tumour suppressor, is silenced by CpG island hypermethylation in gastric cancer,”

Br. J. Cancer, 93

(12), 1395

–1399

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602854 BJCAAI 0007-0920 Google Scholar

P. S. Yanet al.,

“Mapping geographic zones of cancer risk with epigenetic biomarkers in normal breast tissue,”

Clin. Cancer Res., 12

(22), 6626

–6636

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0467 CCREF4 1078-0432 Google Scholar

U. Utzingeret al.,

“Near-infrared Raman spectroscopy for in vivo detection of cervical precancers,”

Appl. Spectrosc., 55

(8), 955

–959

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1366/0003702011953018 APSPA4 0003-7028 Google Scholar

M. D. Kelleret al.,

“Detecting temporal and spatial effects of epithelial cancers with Raman spectroscopy,”

Dis. Markers, 25

(6), 323

–337

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2008/230307 DMARD3 0278-0240 Google Scholar

D. S. Albertset al.,

“Karyometry of the colonic mucosa,”

Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 16

(12), 2704

–2716

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0595 CEBPE4 1055-9965 Google Scholar

F. E. Robleset al.,

“Detection of early colorectal cancer development in the azoxymethane rat carcinogenesis model with Fourier domain low coherence interferometry,”

Biomed. Opt. Express, 1

(2), 736

–745

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/BOE.1.000736 BOEICL 2156-7085 Google Scholar

A. Sharwaniet al.,

“Assessment of oral premalignancy using elastic scattering spectroscopy,”

Oral Oncol., 42

(4), 343

–349

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.oraloncology.2005.08.008 EJCCER 1368-8375 Google Scholar

H. K. Royet al.,

“Association between rectal optical signatures and colonic neoplasia: potential applications for screening,”

Cancer Res., 69

(10), 4476

–4483

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4780 CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

V. Turzhitskyet al.,

“Investigating population risk factors of pancreatic cancer by evaluation of optical markers in the duodenal mucosa,”

Dis. Markers, 25

(6), 313

–321

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2008/958214 DMARD3 0278-0240 Google Scholar

A. J. R. N. N. Mutyalet al.,

“In-vivo risk stratification of colon carcinogenesis by measurement of optical properties with novel lensfree fiber optic probe using low-coherence enhanced backscattering spectroscopy (LEBS),”

in Conf. 8230: Biomedical Applications of Light Scattering VI,

(2012). Google Scholar

N. N. Mutyalet al.,

“In-vivo risk stratification of pancreatic cancer by evaluating optical properties in duodenal mucosa,”

in Biomedical Optics and 3-D Imaging,

BSu5A.10

(2012). Google Scholar

A. J. Radosevichet al.,

“Ultrastructural alterations in field carcinogenesis measured by enhanced backscattering spectroscopy,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 18

(9), 097002

(2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.JBO.18.9.097002 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

J. Yiet al.,

“Can OCT be sensitive to nanoscale structural alterations in biological tissue?,”

Opt. Express, 21

(7), 9043

–9059

(2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.21.009043 OPEXFF 1094-4087 Google Scholar

J. YiV. Backman,

“Imaging a full set of optical scattering properties of biological tissue by inverse spectroscopic optical coherence tomography,”

Opt. Lett., 37

(21), 4443

–4445

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.37.004443 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

J. Yiet al.,

“Inverse spectroscopic optical coherence tomography (ISOCT): non-invasively quantifying the complete optical scattering properties from week scattering tissue,”

in Biomedical Optics and 3-D Imaging,

BTu3A.88

(2012). Google Scholar

S. Bajajet al,

“915 development of novel optical technologies for early colon carcinogenesis detection via nanoscale mass density fluctuations: potential implications for endoscopic diagnostics,”

Gastrointest. Endosc., 75

(4), AB172

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2012.04.146 0016-5107 Google Scholar

D. Huanget al.,

“Optical coherence tomography,”

Science, 254

(5035), 1178

–1181

(1991). http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1957169 Google Scholar

A. F. Fercheret al.,

“Optical coherence tomography—principles and applications,”

Rep. Prog. Phys., 66

(2), 239

–303

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0034-4885/66/2/204 RPPHAG 0034-4885 Google Scholar

D. Levitzet al.,

“Determination of optical scattering properties of highly-scattering media in optical coherence tomography images,”

Opt. Express, 12

(2), 249

–259

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OPEX.12.000249 OPEXFF 1094-4087 Google Scholar

J. M. SchmittA. KnüttelR. F. Bonner,

“Measurement of optical properties of biological tissues by low-coherence reflectometry,”

Appl. Opt., 32

(30), 6032

–6042

(1993). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.32.006032 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

F. J. van der Meeret al.,

“Localized measurement of optical attenuation coefficients of atherosclerotic plaque constituents by quantitative optical coherence tomography,”

IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, 24

(10), 1369

–1376

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TMI.2005.854297 ITMID4 0278-0062 Google Scholar

A. I. Kholodnykhet al.,

“Precision of measurement of tissue optical properties with optical coherence tomography,”

Appl. Opt., 42

(16), 3027

–3037

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.42.003027 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

N. Bosschaartet al.,

“Measurements of wavelength dependent scattering and backscattering coefficients by low-coherence spectroscopy,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 16

(3), 030503

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.3553005 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

C. Xuet al.,

“Characterization of atherosclerosis plaques by measuring both backscattering and attenuation coefficients in optical coherence tomography,”

J. Biomed. Opt., 13

(3), 034003

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1117/1.2927464 JBOPFO 1083-3668 Google Scholar

V. M. Kodachet al.,

“Determination of the scattering anisotropy with optical coherence tomography,”

Opt. Express, 19

(7), 6131

–6140

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OE.19.006131 OPEXFF 1094-4087 Google Scholar

F. E. RoblesS. ChowdhuryA. Wax,

“Assessing hemoglobin concentration using spectroscopic optical coherence tomography for feasibility of tissue diagnostics,”

Biomed. Opt. Express, 1

(1), 310

–317

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/BOE.1.000310 BOEICL 2156-7085 Google Scholar

N. Bosschaartet al.,

“Quantitative measurements of absorption spectra in scattering media by low-coherence spectroscopy,”

Opt. Lett., 34

(23), 3746

–3748

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.34.003746 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

A. J. Radosevichet al.,

“Structural length-scale sensitivities of reflectance measurements in continuous random media under the Born approximation,”

Opt. Lett., 37

(24), 5220

–5222

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.37.005220 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

T. McGarrityL. Peiffer,

“Protein kinase C activity as a potential marker for colorectal neoplasia,”

Digest Dis. Sci., 39

(3), 458

–463

(1994). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02088328 DDSCDJ 0163-2116 Google Scholar

T. J. McGarrityet al.,

“Colonic polyamine content and ornithine decarboxylase activity as markers for adenomas,”

Cancer, 66

(7), 1539

–1543

(1990). http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142 60IXAH 0008-543X Google Scholar

I. Vuceniket al.,

“Usefulness of galactose oxidase-Schiff test in rectal mucus for screening of colorectal malignancy,”

Anticancer Res., 21

(2B), 1247

–1255

(2001). ANTRD4 0250-7005 Google Scholar

C. M. Payneet al.,

“Crypt-restricted loss and decreased protein expression of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I as potential hypothesis-driven biomarkers of colon cancer risk,”

Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 14

(9), 2066

–2075

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0180 CEBPE4 1055-9965 Google Scholar

M. Antiet al.,

“Rectal epithelial cell proliferation patterns as predictors of adenomatous colorectal polyp recurrence,”

Gut, 34

(4), 525

–530

(1993). http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/gut.34.4.525 GUTTAK 0017-5749 Google Scholar

C. Bernsteinet al.,

“A bile acid-induced apoptosis assay for colon cancer risk and associated quality control studies,”

Cancer Res., 59

(10), 2353

–2357

(1999). CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

L.-C. Chenet al.,

“Alteration of gene expression in normal-appearing colon mucosa of APCmin mice and human cancer patients,”

Cancer Res., 64

(10), 3694

–3700

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3264 CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

C.-Y. Haoet al.,

“Altered gene expression in normal colonic mucosa of individuals with polyps of the colon,”

Dis. Colon Rectum, 48

(12), 2329

–2335

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-005-0153-2 DICRAG 0012-3706 Google Scholar

H. Cuiet al.,

“Loss of IGF2 imprinting: a potential marker of colorectal cancer risk,”

Science, 299

(5613), 1753

–1755

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1080902 SCIEAS 0036-8075 Google Scholar

C. R. Danielet al.,

“TGF- expression as a potential biomarker of risk within the normal-appearing colorectal mucosa of patients with and without incident sporadic adenoma,”

Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev., 18

(1), 65

–73

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0732 CEBPE4 1055-9965 Google Scholar

T. Kekuet al.,

“Local IGFBP-3 mRNA expression, apoptosis and risk of colorectal adenomas,”

BMC Cancer, 8

(1), 143

–151

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-8-143 BCMACL 1471-2407 Google Scholar

A. C. J. Polleyet al.,

“Proteomic analysis reveals field-wide changes in protein expression in the morphologically normal mucosa of patients with colorectal neoplasia,”

Cancer Res., 66

(13), 6553

–6562

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0534 CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

A. J. Gomeset al.,

“Rectal mucosal microvascular blood supply increase is associated with colonic neoplasia,”

Clin. Cancer Res., 15

(9), 3110

–3117

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2880 CCREF4 1078-0432 Google Scholar

H. K. Royet al.,

“Spectroscopic microvascular blood detection from the endoscopically normal colonic mucosa: biomarker for neoplasia risk,”

Gastroenterology, 135

(4), 1069

–1078

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.06.046 GASTAB 0016-5085 Google Scholar

H. K. Royet al.,

“Optical measurement of rectal microvasculature as an adjunct to flexible sigmoidosocopy: gender-specific implications,”

Cancer Prev. Res., 3

(7), 844

–851

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0254 DICRAG 0012-3706 Google Scholar

A. AlbiniD. M. NoonanN. Ferrari,

“Molecular pathways for cancer angioprevention,”

Clin. Cancer Res., 13

(15), 4320

–4325

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0069 CCREF4 1078-0432 Google Scholar

R. Z. Chenet al.,

“DNA hypomethylation leads to elevated mutation rates,”

Nature, 395

(6697), 89

–93

(1998). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/25779 NATUAS 0028-0836 Google Scholar

S. B. Baylin,

“DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer,”

Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol., 2

(Suppl 1), S4

–S11

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ncponc0354 1743-4254 Google Scholar

Y. Stypula-Cyruset al.,

“HDAC up-regulation in early colon field carcinogenesis is involved in cell tumorigenicity through regulation of chromatin structure,”

PLoS One, 8

(5), e64600

(2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0064600 1932-6203 Google Scholar

Y. E. Stypulaet al.,

“472 histone deacetylase (HDAC) expression as a biomarker for colorectal cancer (CRC) field carcinogenesis: role in high order chromatin modulation,”

Gastroenterology, 144

(5), S-85

(2013). GASTAB 0016-5085 Google Scholar

A. Razin,

“CpG methylation, chromatin structure and gene silencing–a three-way connection,”

EMBO J., 17

(17), 4905

–4908

(1998). http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/17.17.4905 EMJODG 0261-4189 Google Scholar

F. Fuks,

“DNA methylation and histone modifications: teaming up to silence genes,”

Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev., 15

(5), 490

–495

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2005.08.002 COGDET 0959-437X Google Scholar

N. A. BhowmickE. G. NeilsonH. L. Moses,

“Stromal fibroblasts in cancer initiation and progression,”

Nature, 432

(7015), 332

–337

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature03096 NATUAS 0028-0836 Google Scholar

L. Geet al.,

“Could stroma contribute to field cancerization?,”

Med. Hypotheses, 75

(1), 26

–31

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2010.01.019 MEHYDY 0306-9877 Google Scholar

T. L. Ratliff,

“TGF-β signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia,”

Science, 303

(5659), 848

–851

(2004). http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.1090922 JOURAA 0022-5347 Google Scholar

J. M. SchmittG. Kumar,

“Optical scattering properties of soft tissue: a discrete particle model,”

Appl. Opt., 37

(13), 2788

–2797

(1998). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.37.002788 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

C. Amoozegaret al.,

“Experimental verification of T-matrix-based inverse light scattering analysis for assessing structure of spheroids as models of cell nuclei,”

Appl. Opt., 48

(10), D20

–D25

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.48.000D20 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

J. D. Rogersİ. R. ÇapoğluV. Backman,

“Nonscalar elastic light scattering from continuous random media in the Born approximation,”

Opt. Lett., 34

(12), 1891

–1893

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.34.001891 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

J. SchmittG. Kumar,

“Turbulent nature of refractive-index variations in biological tissue,”

Opt. Lett., 21

(16), 1310

–1312

(1996). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.21.001310 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

C. J. R. Sheppard,

“Fractal model of light scattering in biological tissue and cells,”

Opt. Lett., 32

(2), 142

–144

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.32.000142 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

M. XuR. R. Alfano,

“Fractal mechanisms of light scattering in biological tissue and cells,”

Opt. Lett., 30

(22), 3051

–3053

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.30.003051 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

J. D. Rogerset al.,

“Modeling light scattering in tissue as continuous random media using a versatile refractive index correlation function,”

IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron., 20

(2), 1

–14

(2014). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JSTQE.2013.2280999 IJSQEN 1077-260X Google Scholar

H. G. Davieset al.,

“The use of the interference microscope to determine dry mass in living cells and as a quantitative cytochemical method,”

Q. J. Microsc. Sci., s3-95

(31), 271

–304

(1954). QJMSAF 0370-2952 Google Scholar

R. BarerS. Tkaczyk,

“Refractive index of concentrated protein solutions,”

Nature, 173 821

–822

(1954). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/173821b0 Google Scholar

İ. R. Çapoğluet al.,

“Accuracy of the Born approximation in calculating the scattering coefficient of biological continuous random media,”

Opt. Lett., 34

(17), 2679

–2681

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.34.002679 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

G. Zonioset al.,

“Diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of human adenomatous colon polyps in vivo,”

Appl. Opt., 38

(31), 6628

–6637

(1999). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/AO.38.006628 APOPAI 0003-6935 Google Scholar

R. Doornboset al.,

“The determination of in vivo human tissue optical properties and absolute chromophore concentrations using spatially resolved steady-state diffuse reflectance spectroscopy,”

Phys. Med. Biol., 44

(4), 967

–981

(1999). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/44/4/012 PHMBA7 0031-9155 Google Scholar

M. Huzairaet al.,

“Topographic variations in normal skin, as viewed by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy,”

J. Invest. Dermatol., 116

(6), 846

–852

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01337.x 0022-202X Google Scholar

R. Leitgebet al.,

“Spectral measurement of absorption by spectroscopic frequency-domain optical coherence tomography,”

Opt. Lett., 25

(11), 820

–822

(2000). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.25.000820 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

F. E. RoblesA. Wax,

“Measuring morphological features using light-scattering spectroscopy and Fourier-domain low-coherence interferometry,”

Opt. Lett., 35

(3), 360

–362

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1364/OL.35.000360 OPLEDP 0146-9592 Google Scholar

N. Otsu,

“A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms,”

IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern., 9

(1), 62

–66

(1979). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/TSMC.1979.4310076 ITSHFX 1083-4427 Google Scholar

D. P. Kunteet al.,

“Down-regulation of the tumor suppressor gene C-terminal Src kinase: An early event during premalignant colonic epithelial hyperproliferation,”

FEBS Lett., 579

(17), 3497

–3502

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2005.05.030 FEBLAL 0014-5793 Google Scholar

O. H. Krameret al.,

“The histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid selectively induces proteasomal degradation of HDAC2,”

EMBO J., 22

(13), 3411

–3420

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/emboj/cdg315 EMJODG 0261-4189 Google Scholar

A. M. Bakeret al.,

“Lysyl oxidase enzymatic function increases stiffness to drive colorectal cancer progression through FAK,”

Oncogene, 32

(14), 1863

–1868

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2012.202 ONCNES 0950-9232 Google Scholar

H. Matsubayashiet al.,

“Age- and disease-related methylation of multiple genes in nonneoplastic duodenum and in duodenal juice,”

Clin. Cancer Res., 11

(2), 573

–583

(2005). CCREF4 1078-0432 Google Scholar

H. Matsubayashiet al.,

“DNA methylation alterations in the pancreatic juice of patients with suspected pancreatic disease,”

Cancer Res., 66

(2), 1208

–1217

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2664 CNREA8 0008-5472 Google Scholar

A. J. BannisterT. Kouzarides,

“Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications,”

Cell Res., 21

(3), 381

–395

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/cr.2011.22 1001-0602 Google Scholar

E. W. Y. TungL. M. Winn,

“Epigenetic modifications in valproic acid-induced teratogenesis,”

Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol., 248

(3), 201

–209

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2010.08.001 TXAPA9 0041-008X Google Scholar

H. Royet al.,

“Spectral slope from the endoscopically-normal mucosa predicts concurrent colonic neoplasia: a pilot ex-vivo clinical study,”

Dis. Colon Rectum, 51

(9), 1381

–1386

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10350-008-9384-3 DICRAG 0012-3706 Google Scholar

|