|

|

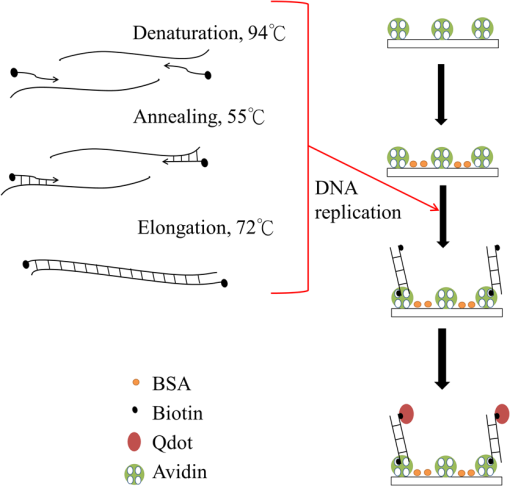

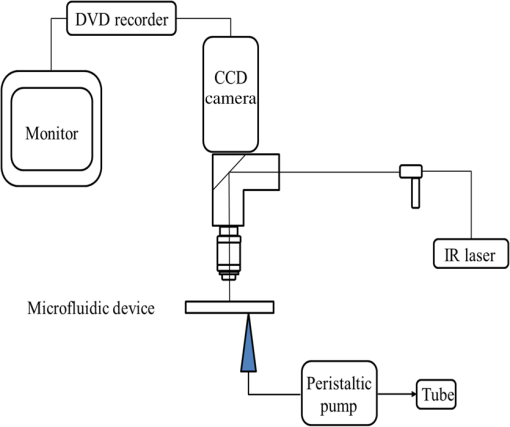

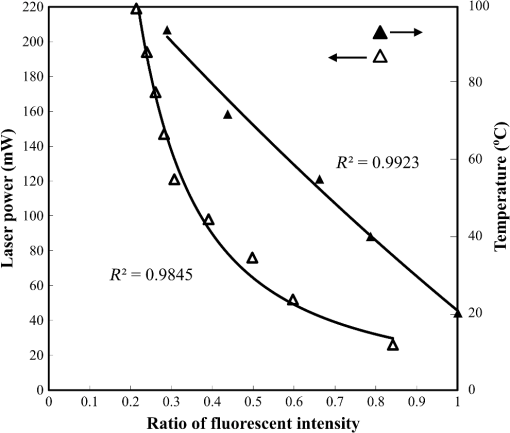

1.IntroductionDNA is a long-chain polymer that contains genetic instructions for guiding biological development and functional operations. With rapid technological developments in recent years, biological nanotechnology has been applied extensively in medical, food, agricultural, and other industries to detect biological samples such as DNA and protein. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is typically used to replicate the target DNA for analysis. However, uneven heating of solution samples occur often in conventional PCR machines because of their low thermal transfer efficiency. Consequently, heating and cooling are time intensive, thereby slowing product replication. Conduction and convection are the primary methods for thermal transfer in most biological nanotechnology-based PCR chips.1–3 The heat capacity of materials must be considered when selecting chip materials because it indirectly affects PCR efficiency. Reducing the sample volume can accelerate heating and cooling, thereby increasing the reaction rate. For example, integrated continuous-flow PCR and microdroplets coated with oil were used to perform PCR thermal cycling in microchannels.4,5 Studies have indicated that PCR thermal cycling can be accelerated by enhancing the heat transfer efficiency of chip materials or by reducing the volume of reaction solutions. However, chip materials must be selected according to the processing procedures and cost effectiveness of chip fabrication. Moreover, solution evaporation during thermal cycling must be accounted for in reducing the solution volume. Therefore, using optical technology as the heat source for PCR processing has attracted increasing research attention. When thermal radiation is used as the heat source in PCR and chips are fabricated using materials transparent to radiation, the radiant energy does not accumulate as heat on the chip surfaces during heating. Thus, in addition to reduce temperature hysteresis in chips, this method accelerates heating and cooling, effectively shortening the duration of PCR operations.6 A laser beam can be focused on a small area and with a high energy concentration, they can heat target objects quickly because of the photothermal effect. Therefore, lasers are often used as the heating source for microfluidic chips.7–15 Furthermore, a laser can be used to heat a specific area of the solution rapidly while preventing the surrounding components from being heated. In addition, switching off the radiant heat source can directly reduce the temperature of the sample without necessitating additional cooling devices. Using a laser-heating system integrated with microfluidic devices, Tan and Takeuchi,10 and Hung and Huang,14 have focused a laser on a heating area which generated bubbles to release cells. Subsequently, a laser was used to induce cell lysates and denature DNA. By using an infrared (IR) laser to irradiate DNA, DNA denaturation can be achieved16–20 and applied to target-sequence detection.19 Because lasers enable the rapid heating of substances, they can be employed to induce microdroplet PCR21–23 and to investigate PCR within microchannels.24 After PCR, the delay before product analysis can affect the target-sequence detection rate. In conventional PCR product detection, the target sequence is detected through agarose gel electrophoresis by using a fluorescent dye (e.g., ethidium bromide; EtBr). However, colloidal production and electrophoresis are time intensive and complex. Therefore, the current methods for increasing PCR product detection speed are primarily based on optical detection technologies which are advantageous because of their ease of observation, rapid detection rate, high sensitivity, and low-detection limit. An example of an optical detection technology is quantitative PCR (qPCR), which is realized by integrating fluorescence sensing and PCR. A major characteristic of qPCR is that calibration is performed during PCR to enable quantitative product analysis: the fluorescence change in the target analyte before and after the reaction is converted into a quantitative relationship. Among the various qPCR systems, fluorescence-based detection technologies are the most advanced and can feature either an intercalating fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBE Green I) or a fluorescent probe (e.g., molecular beacon).25,26 However, real-time qPCR instruments are expensive and large. Therefore, developing a portable qPCR instrument is a critical research focus.27,28 The use of microchannels in the development of micro-PCR chips and relevant detection technology are vital for developing microsystems that are easy to operate. Because of the specific properties of microchannels produced using polydimethyliloxane (PDMS), such as high light transmittance, ease of production, and chemical stability, PDMS has been extensively applied in the development of biomedical microsystems.29–37 Although PDMS has many advantages, it is permeable to gases and organic molecules.38 Many groups have investigated different forms of surface modification to prevent biosamples from being absorbed on the surface of PDMS during PCR; e.g., using compounds such as polyvinylpyrrolidone,39 polybrene,40 bovine serum albumin (BSA),41 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane,28 and glycerol.35 The present study used BSA to prevent biosamples from being absorbed on the surface of microchannels. By integrating a laser optical system with electro-osmotic flow, this study developed a PDMS microfluidic device that can rapidly replicate and detect DNA. An IR laser was used as the heat source for thermal cycles and a DNA sample was replicated directly within the microchannels. Subsequently, avidin–biotin binding was utilized to immobilize one end of the replicated products to the surface of the microchannels. Simultaneously, the fluorescent intensity was used to detect the target sequences following replication. Electro-osmotic flow was utilized to drive solution delivery to the detection area and induce solution flow in the microfluidic device by exploiting the high fluid shear stress at the solid–liquid interface.18,42–47 2.Materials and MethodsIn PCR, which is based on the principle of DNA replication, a forward primer (F-primer) and reverse primer (R-primer) are separately designed for the two ends of the DNA fragments requiring amplification. Furthermore, DNA polymerases (e.g., Taq DNA polymerase) are employed to amplify particular DNA fragments by repeating DNA denaturation, primer annealing, and extension. In this study, a laser was used to heat the target DNA for replication, and the following method was employed to capture the replication products within the microchannels and to demonstrate real-time product detection (Fig. 1). First, avidin–biotin binding was utilized to immobilize one end of the products to the surface of the microchannels. Second, the fluorescent intensity of the quantum dots (Qdots) was used as the basis for product detection. Figure 2 is a schematic depicting the experimental system used in this study. The system comprises a microfluidic device, a peristaltic pump for solution replacement (Ismatec IPC), an IR laser (1455 nm, CW, Raman fiber laser, IPG Laser GmbH), an observation system comprising a microscope (Olympus BX-51, Japan), and an electron bombardment charge-coupled device camera (C7190-23, Hamamatsu, Japan). The relationship between the laser output power and temperature was calibrated using fluorescent dye (*** rhodamine B, Ex , Echo Chemical Co., Ltd., Taiwan)48–52 and a heating plate with temperature control. A few groups have investigated rhodamine B diffusing into PDMS; the result may cause a systematic error in the temperature measurement.48,50–52 To prevent this phenomenon from occurring, the present study conducted laser temperature calibration in a microchannel comprising a coverslip and a glass plate. The temperature in the microchannels was measured using a thermocouple. Each image was analyzed by selecting and averaging the intensity values in a region (representing an area of ). A room-temperature intensity image was initially taken and used to normalize a subsequent intensity image of the same area after heating. Figure 3 shows the calibration results of the 12 experiments. According to Fig. 3, Table 1 lists the operating conditions under which laser heating was employed for thermal cycling. Fig. 3Temperature calibrated curve of laser power in using fluorescence-based temperature measurement.  Table 1Cycle conditions of laser-induced heating and PCR device.

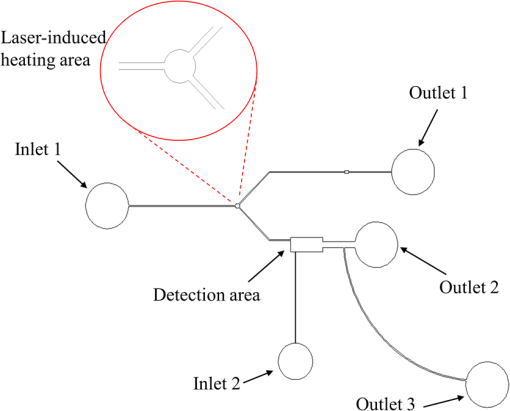

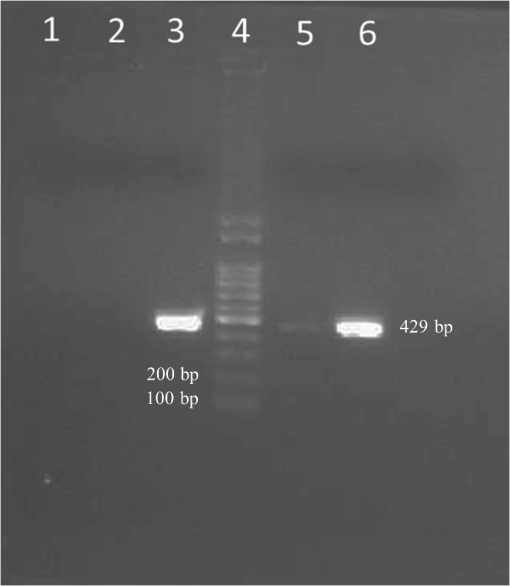

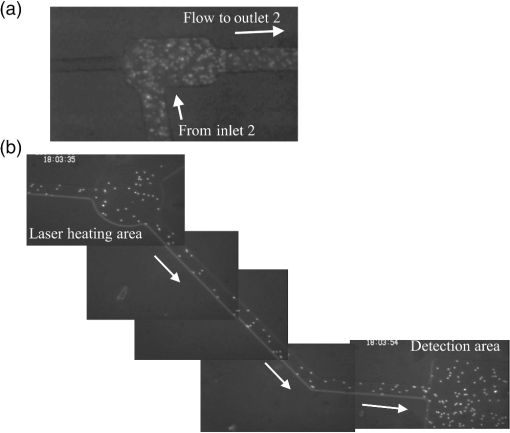

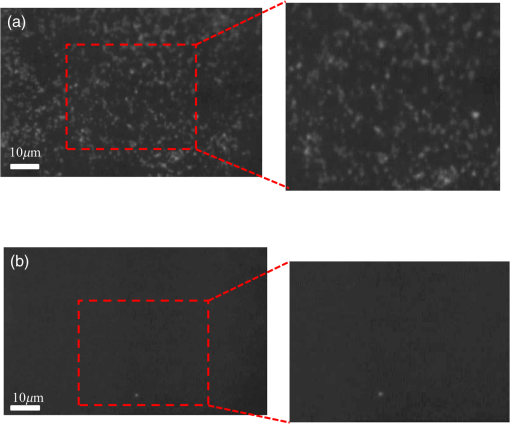

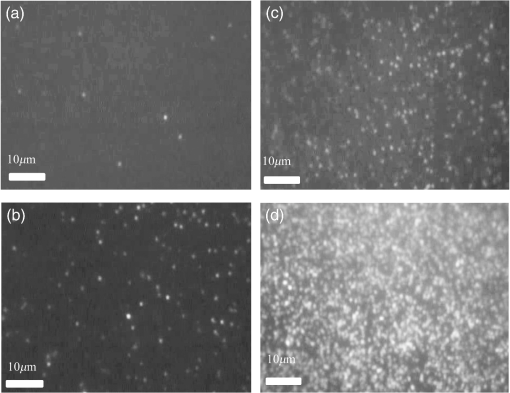

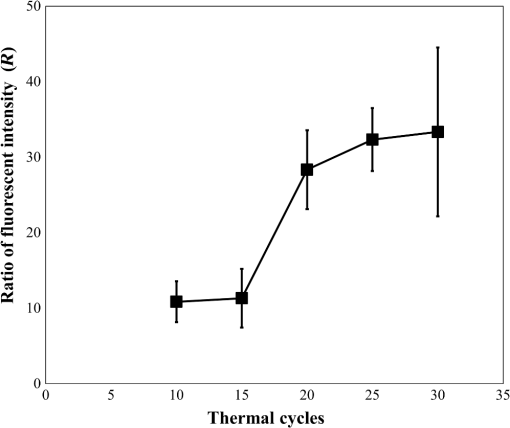

Figure 4 shows the design of the microfluidic device. The sample solutions were injected into the laser-heating area (diameter: ) for DNA replication. Subsequently, electro-osmotic flow was utilized to drive the products into the detection area. The procedure for microfluidic device production is as follows:28,30,37,53 (a) lithography was performed to produce a negative photoresist master mold (SU8-2025, MicroChem). (b) PDMS mixing solution (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning) was used to fabricate a PDMS replica from the SU8 mold. (c) The surface of the PDMS replica was modified using oxygen plasma and bound with a coverslip. The height of the microchannels was approximately . The test sample used in this study was (48502 bp), and fluorescent dye (YO-PRO-1, ) was used to stain the DNA. The positions of replication were from 24,808 to 25,237 bp on the 5′ end of the λDNA (replication length: 429 bp). The biotinylated primers with biotin on the 5′ end (Mission Biotech Co., Taiwan), as designed in this study, were F-primer: 5′-GTCTTCCTGCCTCCAGTTC-3′ and R-primer: 5′-TTACCTACGACAGGACACAC-3′. Prior to the experiment, avidin was prepared in the detection area and Qdots were injected to confirm the Qdot adsorption on the surface of the microchannels. The experimental procedure is described as follows:18 (1) of avidin in a pH 7.2 buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 50 mM KCl) was injected into the detection area [inlet 2 → putlet 2 of Fig. 4, as shown in Fig. 5(a) (the photo was artificially brightened)] and incubated at 25°C for 50 min. (2) The buffer was used to wash away any surplus avidin (inlet 2 → outlet 2 of Fig. 4). (3) BSA solution (, Sigma-Aldrich Co.) was injected into the detection area (inlet 1 → outlet 2 of Fig. 4) and incubated at 25°C for 20 min to block the adsorption of the biosamples and Qdots onto to the microchannel surface. (4) A 1 nM Qdot (Qdots 655 with streptavidin, Em 653 nm, , Invitrogen Co.) was injected into the detection area (inlet 2 → outlet 2 of Fig. 4) and incubated at 25°C for 50 min. (5) The buffer was used to rinse away any surplus Qdots (inlet 2 → outlet 2 of Fig. 4). Fig. 5Visualization of flow used in fluorescent microspheres (): (a) injecting flow (photo was artificially brightened) and (b) electro-osmotic flow from the laser-heating area to the detection area.  Subsequently, the DNA in the microchannels was replicated and detected. The procedure is described as follows: (1) The sample solution ( of , YO-PRO-1, 1% -methylphenethylamine, biotinylated F-primer, biotinylated R-primer, 0.2 mM dNTP, of Pro Taq DNA Polymerase, buffer) was injected into the laser-heating area (inlet 1 → outlet 1 of Fig. 4). (2) Laser heating was employed to replicate the DNA. (3) Electro-osmotic flow (DC ) was used to deliver the products to the detection area [Fig. 5(b)] for incubation at 25°C for 40 min. (4) The buffer was used to rinse surplus products (inlet 2 → outlet 2 of Fig. 4). (5) Qdots (1 nM) were injected into the detection area (inlet 2 → outlet 2 of Fig. 4) and incubated at 25°C for 50 min. (6) The buffer was used to rinse any surplus Qdots (inlet 2 → outlet 2 of Fig. 4). Blocking and washing were of particular importance to ensure that a favorable signal-to-noise ratio was achieved. Theoretically, approximately avidin molecules were coated in the detection area (the volume of the detection area was and the molecular weight of avidin was 69,000 Da), and the laser spot was approximately in diameter. The heating area was located within the laser spot. Therefore, approximately molecules were replicated in the laser-heating area (the volume of the laser-heating area was and the molecular weight of is ). Furthermore, the number of primers was approximately , and approximately Qdots entered the detection area. 3.Results and DiscussionBSA-coated Qdots and uncoated Qdots were injected into the microchannels and incubated for 50 min after the surface of the microchannels was coated with avidin; subsequently, the buffer was used to rinse surplus Qdots. Figure 6 shows the nonspecific adsorption of these Qdots on the surface of the microchannels and indicates that coating the surface with BSA effectively reduced the nonspecific adsorption of Qdots on the surface of the microchannels. (Please note that the photos were artificially brightened.) BSA coating on the microchannels can effectively block the adsorption of Qdots; it also can block biosamples adsorbed onto the microchannels of PDMS during the DNA replication process. As mentioned regarding previous studies,28,35,38–41 modifying PDMS microchannels is necessary for successful DNA replication. Our experiment revealed that this result was also true for our DNA replication microchannels. When the sample of the mixture was injected into the laser-heating area of the PDMS microchannels without modification in our work, the fluorescence of was almost observed on the surface of the microchannels rather than in the solution (because of the adsorption on the surface of the microchannels), thus exhibiting DNA replication failure (data not shown). Fig. 6Fluorescent images of Qdots (photos were artificially brightened) on the microchannel surfaces: (a) without BSA and (b) coating with BSA.  A solution was injected into the laser-heating area of the microchannels for replication. To investigate whether solution evaporation occurred, this study used microchannels with and without a droplet of mineral oil at the inlet of the microfluidics during laser irradiation. In the experiment, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 thermal cycles were performed. No bubble was generated in the microchannels, even without mineral oil and at 30 thermal cycles through laser-induced heating. The result is consistent with that of our previous study: bubbles could be generated at a laser power greater than 157 mW14 (94°C at a laser power of 144 mW in the present work). The reason may be that the laser irradiation area was small, the temperature was lower than the boiling point of the solution, and the pressure was not acutely changed in the microchannels during the laser-induced heating process in our experiment.54 Figures 7(a)–7(d) show the fluorescent intensity of the Qdots adsorbed on the surface of the microchannels after 10, 20, 25, and 30 thermal cycles, respectively. (Please note that the photos of Fig. 7 were artificially brightened.) Clearly, the fluorescent intensity of the Qdots adsorbed on the surface of the microchannels after replication increased with the number of thermal cycles, indicating that more products bound to avidin on the surface of the microchannels. Notably, the velocity of electro-osmotic flow is critical for carrying the replicated products to the detection area for successful detection. If the time of the applied field is longer or shorter, the products flow through the detection area and toward the outlet or cannot flow into the detection area, respectively. Therefore, the velocity of electro-osmotic flow must be measured before DNA replication. In our work, the velocity of electro-osmotic flow was [Fig. 5(b)] and the time of the applied field was 15 s for carrying the products toward the detection area. In addition, the PDMS microchannels can be used only once for DNA replication and detection because the avidin on the surface of the detection area was bound and occupied by the replicated products. Fig. 7Fluorescent images of Qdots (photos were artificially brightened) on the microchannel surfaces after thermal cycles of (a) 10, (b) 20, (c) 25, and (d) 30 through laser-induced heating.  The fluorescent intensity of the Qdots can be expressed as , where denotes the fluorescent intensity of the Qdots adsorbed to the surface of the microchannels after DNA replication, is the fluorescent intensity of Qdots attached to the surface of microchannels before DNA replication, and is the background intensity of the surface of the microchannels.55 These fluorescence intensities [distribution of gray values (max: 256; min: 0) of the total pixels in the image] were calculated using a commercial image-processing software (ImageJ). indicates a difference in the calculated and background intensities. The area of the surface of the microchannels within the detection area for the calculation was . Figure 8 shows the calculated results. exceeded 10 when the number of thermal cycles was only 10, indicating that the fluorescent intensity of the Qdots differed considerably before and after replication. exceeded 25 when the number of thermal cycles was 20, indicating that more postreplicated products had bound with the avidin on the surface of the microchannels. When the number of thermal cycles exceeded 20, the increase in slowed, possibly because most of the avidin on the surface of the microchannels had already bound to the postreplicated products. Regarding the theoretical efficiency of DNA amplification, approximately products (slightly greater than the number of avidins in the detection area) and (-fold that of the avidins) were formed when the numbers of thermal cycles were 20 and 30, respectively. Therefore, beyond 20 thermal cycles, the increase in the number of replicated products did not result in a significant increase in the fluorescent intensity of the Qdots, which is attributable to the saturated binding between the products and the avidins in the detection area. Fig. 8Calculated results of fluorescent intensity at various thermal cycles through laser-induced heating.  To compare gel electrophoresis detection with the proposed method, we recovered the replication products in the microchannels obtained through laser-induced heating, and agarose gel electrophoresis was used to detect the products. The results are listed in Fig. 9: column 4 indicates the marker; columns 3 and 6, respectively, indicate the replicated products after 20 and 30 thermal cycles of using PCR devices (cycling conditions shown in Table 1); and columns 1, 2, and 5 indicate the replicated products obtained after 20, 25, and 30 thermal cycles, respectively, through laser-induced heating. In the gel electrophoresis method, the replicated products that involved using laser-induced heating were detected only after 30 thermal cycles (Fig. 9), implying that the DNA was insufficient. By contrast, in the proposed method, the products were detected in thermal cycles. Therefore, compared with gel electrophoresis-based detection methods, the proposed method is significantly more sensitive and faster. 4.ConclusionsThis study developed a real-time microfluidic platform for DNA replication and detection that exhibits the features of portability, rapid heating, cooling, and high-detection sensitivity. Microchannels were sectioned into a laser-heating area and a detection area, and an IR laser was used as the heat source for thermal cycling. The replicated products were driven to the detection area through electro-osmotic flow. Finally, the fluorescent intensity of the Qdots was used to detect the replicated products. This study demonstrated that surface coating microchannels with BSA effectively inhibits nonspecific adsorption of Qdots. Additionally, because of the design of the biotinylated primers, biotins on one end of the replicated products bind to the avidins on the surface of the microchannels, thereby becoming immobilized. Moreover, the biotins on the other end of the products bind to the Qdots. Therefore, the fluorescent intensity of the Qdots can be used to detect the products in real time. Compared with gel electrophoresis-based detection methods, the developed method entails avidin–biotin binding for direct and more sensitive product detection in microchannels. Through this method, the products can be detected after only 10 thermal cycles of laser-induced heating, thus achieving superior detection sensitivity. Furthermore, because a laser was used as the heat source, no heater is required in the microchannels; thus, a simple microchannel design is realized. The method enables rapid heating and cooling and thus can be applied to microanalysis systems for analyzing microliter samples such as those in microdroplet-based microfluidics. AcknowledgmentsWe thank Professor Masao Washizu and Professor Hidehiro Oana of the University of Tokyo, and Professor Yu-Yuan P. Wo of National Chiayi University for valuable discussions. The authors deeply appreciate the partial financial support by the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (Grant Nos. NSC 102-2628-B-415-001-MY2 and MOST 104-2313-B-415-005). ReferencesM. Bu et al.,

“Design and theoretical evaluation of a novel microfluidic device to be used for PCR,”

J. Micromech. Microeng., 13

(4), S125

–S130

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0960-1317/13/4/321 PRLTAOJMMIEZ 0031-90070960-1317 Google Scholar

H. Gong et al.,

“Microfluidic handling of PCR solution and DNA amplification on a reaction chamber array biochip,”

Biomed. Microdevices, 8

(2), 167

–176

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10544-006-7712-8 Google Scholar

Y.-F. Hsieh et al.,

“Polymerase chain reaction with phase change as intrinsic thermal control,”

Appl. Phys. Lett., 102

(17), 173701

(2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4803442 APPLAB 0003-6951 Google Scholar

S. Park et al.,

“Advances in microfluidic PCR for point-of-care infectious disease diagnostics,”

Biotechnol. Adv., 29

(6), 830

–839

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.06.017 BIADDD 0734-9750 Google Scholar

W. Wu, K.-T. Kang and N.-Y. Lee,

“Bubble-free on-chip continuous-flow polymerase chain reaction: concept and application,”

Analyst, 136

(11), 2287

–2293

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c0an01034k ANLYAG 0365-4885 Google Scholar

G. P. McDermott et al.,

“Multiplexed target detection using DNA-binding dye chemistry in droplet digital PCR,”

Anal. Chem., 85

(23), 11619

–11627

(2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac403061n ANCHAM 0003-2700 Google Scholar

M. N. Slyadnev et al.,

“Photothermal temperature control of a chemical reaction on a microchip using an infrared diode laser,”

Anal. Chem., 73

(16), 4037

–4044

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac010318p ANCHAM 0003-2700 Google Scholar

T. Arakawa et al.,

“High-speed particles and biomolecules sorting microsystem using thermosensitive hydrogel,”

Meas. Sci. Technol., 17

(12), 3141

–3146

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/0957-0233/17/12/S04 MSTCEP 0957-0233 Google Scholar

M. A. Yaseen et al.,

“Laser-induced heating of dextran-coated mesocapsules containing indocyanine green,”

Biotechnol. Prog., 23

(6), 1431

–1440

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/bp0701618 Google Scholar

W.-H. Tan and S. Takeuchi,

“Dynamic microarray system with gentle retrieval mechanism for cell-encapsulating hydrogel beads,”

Lab Chip, 8

(2), 259

–266

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/B714573J Google Scholar

L. H. Thamdrup, N. B. Larsen and A. Kristensen,

“Light-induced local heating for thermophoretic manipulation of DNA in polymer micro- and nanochannels,”

Nano Lett., 10

(3), 826

–832

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/nl903190q NALEFD 1530-6984 Google Scholar

A. Q. Jian et al.,

“Microfluidic flow direction control using continuous-wave laser,”

Sens. Actuators A, 188 329

–334

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2012.02.002 Google Scholar

W. Lee and X. Fan,

“Intracavity DNA melting analysis with optofluidic lasers,”

Anal. Chem., 84

(21), 9558

–9563

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac302416g ANCHAM 0003-2700 Google Scholar

M.-S. Hung and Y.-T. Huang,

“Laser-induced heating for cell release and cellular DNA denaturation in a microfluidics,”

Biochip J., 7

(4), 319

–324

(2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13206-013-7402-6 Google Scholar

N. E. Dina et al.,

“Structural changes induced in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) DNA by femtosecond IR laser pulses: a surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopic study,”

Nanomaterials, 6

(6), 96

(2016). http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/nano6060096 Google Scholar

P. Baaske, S. Duhr and D. Braun,

“Melting curve analysis in a snapshot,”

Appl. Phys. Lett., 91

(13), 133901

(2007). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.2790806 APPLAB 0003-6951 Google Scholar

C. B. Mast and D. Braun,

“Thermal trap for DNA replication,”

Phys. Rev. Lett., 104

(18), 188102

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.188102 Google Scholar

M.-S. Hung, O. Kurosawa and M. Washizu,

“Single DNA molecule denaturation using laser-induced heating,”

Mol. Cell. Probes, 26

(3), 107

–112

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mcp.2012.03.008 Google Scholar

E. K. Wheeler et al.,

“On-chip laser-induced DNA dehybridization,”

Analyst, 138

(13), 3692

–3696

(2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c3an00288h ANLYAG 0365-4885 Google Scholar

R. Zhao et al.,

“Laser-assisted single-molecule refolding (LASR),”

Biophys. J., 99

(6), 1925

–1931

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.019 BIOJAU 0006-3495 Google Scholar

H. Terazono et al.,

“Development of a high-speed real-time polymerase chain reaction system using a circulating water-based rapid heat-exchange,”

Jpn. J. Appl. Phys., 49

(6s), 06GM05

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1143/JJAP.49.06GM05 Google Scholar

K. Hettiarachchi, H. Kim and G. W. Faris,

“Optical manipulation and control of real-time PCR in cell encapsulating microdroplets by IR laser,”

Microfluid. Nanofluid., 13

(6), 967

–975

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10404-012-1016-5 Google Scholar

H. Kim, S. Vishniakou and G. W. Faris,

“Petri dish PCR: laser-heated reactions in nanoliter droplet arrays,”

Lab Chip, 9

(9), 1230

–1235

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/b817288a Google Scholar

Y. Yu et al.,

“Quantitative polymerase chain reaction using infrared heating on a microfluidic chip,”

Anal. Chem., 84

(6), 2825

–2829

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac203307h ANCHAM 0003-2700 Google Scholar

D. K. Yang et al.,

“Selection of aptamers for fluorescent detection of alpha-methylacyl-CoA racemase by single-bead SELEX,”

Biosens. Bioelectron., 62 106

–112

(2014). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bios.2014.06.027 BBIOE4 0956-5663 Google Scholar

K.-C. Li et al.,

“Melting analysis on microbeads in rapid temperature-gradient inside microchannels for single nucleotide polymorphisms detection,”

Biomicrofluidics, 8

(6), 064109

(2014). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4902907 1932-1058 Google Scholar

D. Sugumar et al.,

“Rapid multi sample DNA amplification using rotary-linear polymerase chain reaction device (PCRDisc),”

Biomicrofluidics, 6

(1), 014119

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3690469 1932-1058 Google Scholar

D. Khodakov et al.,

“DNA capture-probe based separation of double-stranded polymerase chain reaction amplification products in poly(dimethylsiloxane) microfluidic channels,”

Biomicrofluidics, 6

(2), 026503

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4729131 1932-1058 Google Scholar

S. W. Rhee et al.,

“Patterned cell culture inside microfluidic devices,”

Lab Chip, 5

(1), 102

–107

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/b403091e Google Scholar

K.-Y. Lien et al.,

“Microfluidic systems integrated with a sample pretreatment device for fast nucleic-acid amplification,”

J. Microelectromech. Syst., 17

(2), 288

–301

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JMEMS.2008.916295 JMIYET 1057-7157 Google Scholar

N. Ramalingam et al.,

“Real-time PCR-based microfluidic array chip for simultaneous detection of multiple waterborne pathogens,”

Sens. Actuators B, 145

(1), 543

–552

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2009.11.025 Google Scholar

J. S. Kuo and D. T. Chiu,

“Disposable microfluidic substrates: transitioning from the research laboratory into the clinic,”

Lab Chip, 11

(16), 2656

–2665

(2011). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c1lc20125e Google Scholar

J. H. L. Beal et al.,

“A rapid, inexpensive surface treatment for enhanced functionality of polydimethylsiloxane microfluidic channels,”

Biomicrofluidics, 6

(3), 36503

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4740232 1932-1058 Google Scholar

C. S. Thompson and A. R. Abate,

“Adhesive-based bonding technique for PDMS microfluidic devices,”

Lab Chip, 13

(4), 632

–635

(2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c2lc40978j Google Scholar

N. B. Trung et al.,

“Multi-chamber PCR chip with simple liquid introduction utilizing the gas permeability of polydimethylsiloxane,”

Sens. Actuators B Chem., 149

(1), 284

–290

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2010.06.013 Google Scholar

A. C. Hatch et al.,

“Continuous flow real-time PCR device using multi-channel fluorescence excitation and detection,”

Lab Chip, 14

(3), 562

–568

(2014). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/C3LC51236C Google Scholar

M.-S. Hung and H.-Y. Chang,

“A simple microfluidics for real time plasma separation and hCG detection from whole blood,”

J. Chin. Inst. Eng., 38

(6), 685

–691

(2015). http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02533839.2015.1010455 Google Scholar

M. M. Kim et al.,

“The improved resistance of PDMS to pressure-induced deformation and chemical solvent swelling for microfluidic devices,”

Microelectron. Eng., 124 66

–75

(2014). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mee.2014.04.041 MIENEF 0167-9317 Google Scholar

J. A. Kim et al.,

“Fabrication and characterization of a PDMS-glass hybrid continuous-flow PCR chip,”

Biochem. Eng. J., 29

(1–2), 91

–97

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bej.2005.02.032 BEJOFV 1369-703X Google Scholar

D. Erickson et al.,

“Electrokinetically based approach for single-nucleotide polymorphism discrimination using a microfluidic device,”

Anal. Chem., 77

(13), 4000

–4007

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac050236r ANCHAM 0003-2700 Google Scholar

T. Nakayama et al.,

“Circumventing air bubbles in microfluidic systems and quantitative continuous-flow PCR applications,”

Anal. Bioanal. Chem., 386

(5), 1327

–1333

(2006). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00216-006-0688-7 ABCNBP 1618-2642 Google Scholar

C. Chen and J. G. Santiago,

“A planar electroosmotic micropump,”

J. Microelectromech. Syst., 11

(6), 672

–683

(2002). http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/JMEMS.2002.805055 JMIYET 1057-7157 Google Scholar

M. Washizu et al.,

“Stretching yeast chromosomes using electroosmotic flow,”

J. Electrostatics, 57

(3–4), 395

–405

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3886(02)00176-6 JOELDH 0304-3886 Google Scholar

X. Wang et al.,

“Electroosmotic pumps and their applications in microfluidic systems,”

Microfluid. Nanofluid., 6

(2), 145

–162

(2009). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10404-008-0399-9 Google Scholar

Y. Ai et al.,

“A low-voltage nano-porous electroosmotic pump,”

J. Colloid Interface Sci., 350

(2), 465

–470

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2010.07.024 JCISA5 0021-9797 Google Scholar

M.-S. Hung et al.,

“Stretching DNA fibers out of a chromosome in solution using electroosmotic flow,”

J. Chin. Soc. Mech. Eng., 30

(4), 289

–295

(2009). CCHPEK 0257-9731 Google Scholar

M.-S. Hung and P.-C. Chen,

“Extending DNA from a single cell using integrated system of electro-osmosis and AFM,”

J. Med. Biol. Eng., 30

(1), 29

–34

(2010). IYSEAK 0021-3292 Google Scholar

D. Ross et al.,

“Temperature measurement in microfluidic systems using a temperature-dependent fluorescent dye,”

Anal. Chem., 73

(17), 4117

–4123

(2001). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac010370l ANCHAM 0003-2700 Google Scholar

D. Erickson, D. Sinton and D. Li,

“Joule heating and heat transfer in poly(dimethylsiloxane) microfluidic systems,”

Lab Chip, 3

(3), 141

–149

(2003). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/b306158b Google Scholar

R. Samy, T. Glawdel and C. L. Ren,

“Method for microfluidic whole-chip temperature measurement using thin-film poly(dimethylsiloxane)/ rhodamine B,”

Anal. Chem., 80

(2), 369

–375

(2008). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ac071268c ANCHAM 0003-2700 Google Scholar

S. H. Lee et al.,

“Use of directly molded poly(methyl methacrylate) channels for microfluidic applications,”

Lab Chip, 10

(23), 3300

–3306

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c0lc00127a Google Scholar

H. Sasaki et al.,

“Parylene-coating PDMS microfluidic channels prevents the absorption of fluorescent dyes,”

Sens. Actuators B, 150

(1), 478

–482

(2010). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2010.07.021 Google Scholar

M.-S. Hung and Y.-T. Chang,

“Single cell lysis and DNA extending using electroporation microfluidic device,”

Biochip J., 6

(1), 84

–90

(2012). http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13206-012-6111-x Google Scholar

T. Sato et al.,

“Evidence for hydrogen generation in laser- or spark-induced cavitation bubbles,”

Appl. Phys. Lett., 102

(7), 074105

(2013). http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4793193 APPLAB 0003-6951 Google Scholar

H. Du et al.,

“Sensitivity and specificity of metal surface-immobilized molecular beacon biosensors,”

J. Am. Chem. Soc., 127

(21), 7932

–7940

(2005). http://dx.doi.org/10.1021/ja042482a JACSAT 0002-7863 Google Scholar

BiographyMin-Sheng Hung is a professor at the National Chiayi University of Taiwan. He received his BS and MS degrees in engineering from the National Cheng Kung University and National Taiwan University in 1993 and 1995, respectively, and his PhD in mechanical engineering from National Taiwan University in 2001. He is a reviewing associate editor of an EI Compendex (Engineering Village) journal, and has written two book chapters. His current research interests include laser and bionanotechnology. |