|

|

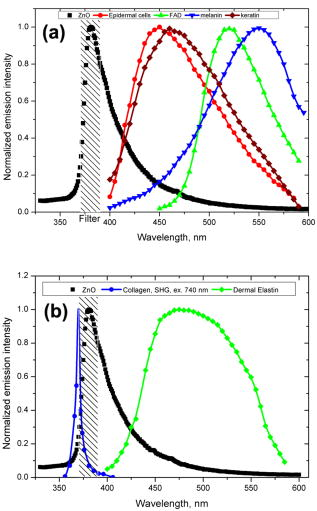

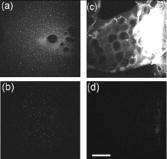

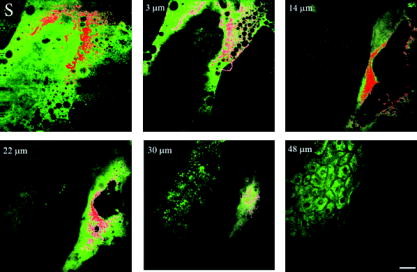

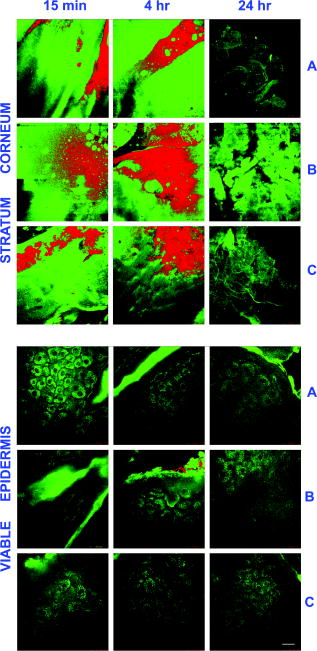

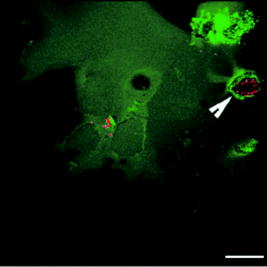

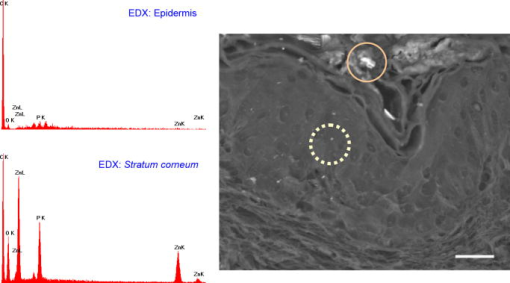

1.IntroductionNanomaterials including nanoemulsions, nanosomes, and nanoparticles are employed as active components1, 2 and delivery vehicles3, 4 in cosmetics and medicine. One example of a nanotechnology application is the widespread use of zinc oxide (ZnO-nano) and titanium dioxide nanoparticles as ingredients in cosmetic and sun-blocking creams. These nanomaterials are efficient absorbers of the ultraviolet (UV) radiation: ZnO absorbs both UVA and UVB radiation and reemits them as less damaging UVA or as visible fluorescence (and is dictated by the need to minimize skin damage due to UV light and potential consequences such as skin cancer). The use of these sun-blocking creams is widespread in Australia, where over 250,000 people are diagnosed with nonmelanoma skin cancer, and over 8000 with melanoma annually.5 The upper size limit for ZnO and nanoparticles is dictated by the aesthetic marketing value of transparent sun-blocking creams. Transparency is achieved by reducing scattering efficiency of ZnO particles, which are normally white and visible, by using a nanoparticle size of less than , its transparency threshold.6 An inevitable question then is whether there a potential toxicity of these nanoparticles whose size may be small enough to allow them to penetrate the skin. The extent of nanoparticles penetration through the topmost layer of the skin, stratum corneum (average thickness, less than ) into the viable epidermis, is hotly debated. As an illustration, the studies of Alvarez-Roman shows no penetration through excised human skin.6 In contrast, Ryman-Rasmussen33 show extensive penetration of neutral, positively charged and negatively charged quantum dots through pig skin. In vitro cytotoxicity of ZnO-nano to epidermal (and, especially, epithelial) cells can occur and have been attributed to free radical generation (mainly via hydroxyl radicals formed through oxidation), causing adverse effects in isolated cell experiments.8, 9 Conventional scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy and Franz cell penetration involve indirect or/and destructive sampling of skin that limits the experimental methods to in vitro observations. Optical microscopy of nanoparticle distribution in skin in vivo is precluded due to high scattering efficiency of the superficial layers of skin, especially human skin. Fluorescence confocal microscopy has enabled production of clear subsurface images of skin at depths down to at the micrometer resolution by way of “optical sectioning” thin layers of the specimen. The skin morphology contrast is derived from the skin autofluorescence, although often requires additional staining. The visibility of nanoparticles depends on their fluorescent properties, which limits the choice to the following materials: micro- and nanobeads impregnated with fluorescence dye molecules, photoluminescent nanomaterials, quantum dot (Qdot) structures,10 and emerging nanocrystals with color centers.11 Fabrication of nanobeads impregnated with fluorescent dye is difficult and they are prone to photobleaching. Qdots are cytotoxic, thus, posing hazard for in vivo applications on humans. Although silica Qdots are less cytotoxic, their photoluminescence (PL) degradation and complex passivation chemistry makes their application cumbersome and expensive.12 PL materials, such as semiconductor metal oxides, are either toxic, radiation-inefficient (due to the indirect band gap structure), or rare. In contrast, ZnO-nano represents a promising nanomaterial that is widespread, inexpensive, and has proven to be suitable for cosmetic care and pharmacy. Its production is straightforward, yielding nanoparticle of various sizes and shapes, starting from and larger.7, 13 ZnO material properties, including a direct wide bandgap electronic structure, and high exciton energy of (compare to that of of cadmium selenide), are very attractive for a new generation of electro-optic devices, e.g., light-emitting diodes and lasers in the UV spectral range. The wide bandgap of ZnO requires excitation at a wavelength of in the UV spectral range, with principle emission at , as shown in Fig. 1 (scattered squares graph). This excitation requirement is problematic for application of ZnO-nano in optical biomedical imaging. First, UV photons efficiently excite a number of intrinsic (endogenous) fluorophores in skin that produce a broadband autofluorescence background. Among these, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide/nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAD[P]H), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), and porphyrins contribute 75, 25, and 2% to the skin autofluorescence, with their respective fluorescence bands centered at 425, 520, and (Ref. 15) [also see Fig. 1a]. Second, UV radiation is heavily absorbed and scattered by the skin tissue, severely limiting imaging penetration depth. Hence, optical imaging of thick skin tissue using UV light is not practical. Fig. 1Emission spectrum of ZnO-nano at an excitation wavelength of (scatter plot, squares) superimposed on TPEF spectra of (a) epidermal cells (circles), similar to a spectrum of NAD[P]H; FAD (triangles); melanin (inverted triangles); keratin (diamonds), adapted from Ref. 14; and (b) elastin (diamonds), similar to collagen, adapted from Ref. 14; and the second-harmonic generation (SHG) spectrum of collagen calculated at a fundamental wavelength. A dashed area designates FWHM of the bandpass filter BP380 used to discriminate ZnO PL signal against the skin autofluorescence.  It has been recently found that the zinc oxide structure is efficiently excited via a nonlinear optical process of simultaneous absorption of two or three photons under illumination by an ultrashort-pulse laser.16 This shifts the ZnO excitation band to the infrared (IR) range, where the ultrashort-pulse laser sources predominantly operate, falling into the so-called therapeutic window, , wherein the maximum imaging penetration depth in tissue of is attainable. The increased penetration depth is due, first, to the markedly reduced absorption of the major tissue constituents, including proteins, hemoglobin, and melanin in the UV/visible spectral range, and the water transparency window; and, second, to the reduced scattering efficiency of skin tissue at longer wavelengths. In this paper, we communicate our results on application of multiphoton microscopy to study of ZnO nanoparticles penetration in human skin in vitro and in vivo. This is the first time, to the best of our knowledge, that the in vivo observation of inorganic PL nanoparticles in the morphology context of live cells and tissue has been reported. This will enable imaging of a new class of engineered nanostructures as applied to transdermal delivery and toxicology. 2.Materials and Methods2.1.MaterialsDr. Lewinns’ private formula (19% w/w) (Advanced Nanotechnology Ltd., WA, Australia) is comprised of mean size ZnO particles with preservatives of phenoxyethanol (0.3% w/w) and hydroxybenzoates (0.3% w/w) suspended in caprylic capric triglycerides.17 These nanoparticles were fabricated by using the mechanochemical processing technology based on dry milling that induced chemical reactions through ball-powder collisions resulting in nanoparticle formation within a salt matrix. Particle size was determined by the chemistry of the reactant mixture, milling and heat treatment conditions. For in vivo experiments, an area of of skin was selected on the forearm, cheek, shoulder, or feet of the subject and cleaned with ethanol. Four subjects of different ethnic background participated in this experiment: two Caucasian males, one Indian male, and a Chinese female aged 30 to 40, 40 to 50, and , respectively. For in vitro study, excised abdominal or breast human skin was obtained after plastic surgery. 2.2.Sample TreatmentApproximately of commercial Dr Lewinns’ sun-blocking special formulation was applied evenly to the selected area of the human subjects and rubbed in for . The small amount was chosen arbitrarily to represent normal user application conditions. The area of application was small in comparison with the normal application of sunscreens for sun-blocking purposes. Subsequently, the treated area was noninvasively imaged using the multiphoton imaging system. A drop of water was applied to the region of skin being studied, followed by a -thick microscope glass cover slip to ensure aberration-free imaging, and finally immersion oil between the coverslip and objective lens. Images were acquired in three sessions: (1) immediately, (2) after , and (3) after the topical application, following washing. After session 1, the subject was allowed to move, as per usual daily routine. Session 3 was carried out following a shower at night, where the sun-blocking cream residue was washed away from the superficial layers of the skin. The rationale behind the times at which the images were carried out are as follows. Imaging immediately after application served as a control for time-lapse imaging. Imaging after was chosen as a representation of outdoors activities of the native population of southeast Queensland. The imaging was performed to verify whether prolonged exposure to sunscreens had any bearing on the ZnO penetration. All experiments conducted on human subjects were done with approval of Princess Alexandra Hospital Research Committee (Approval No. 097/090, administrated by the University of Queensland Human Ethics Committee). Each subject gave written consent. 2.3.Scanning Electron Microscope and Energy-Dispersive X-Ray MicroanalysisWe employed a Philips XL30 FEG scanning electron microscope (SEM), with a backscattered electron detector and an integrated energy-dispersive x-ray (EDX) microanalysis system. The following procedure was used for sample preparation for SEM/EDX imaging and microanalysis. The ZnO nanoparticle formulation was applied to the excised skin sample, and incubated for . Several skin patches were tape-stripped 10 to 20 times on the areas of interest, while the other patches remained untouched. These nanoparticle-treated skin samples were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution, a requirement of the SEM facilities used and workplace health and safety protocols, prior to freeze drying. Before imaging, all the samples were vacuum-coated with a carbon coating. Conductive paint was applied to the aluminium stub holder. The SEM was operated at a acceleration voltage and high vacuum, demanding all organic tissue to be fixed and dried. Images were obtained at a working distance (the distance between lens and the sample stage). The numerical aperture (NA) was 6, and coarse was in the standard microscope settings. Focus, brightness, and contrast were adjusted for each image. The fixed skin was cut into small cubical shape blocks approximately and snap-frozen with a specially made copper press that had been dipped in liquid nitrogen for . The samples were further dipped while in the press in liquid nitrogen and then freeze-dried. The small freeze-dried skin samples were mounted on the SEM, and imaged immediately. 2.4.Multiphoton ImagingIn the multiphoton microscopy (MPM) imaging system (JenLab GmbH Schillerstraße 107745 Jena Germany), ultrashort-pulse excitation laser light was tightly focused onto a sample by using a high-NA oil-immersion microscope objective ( , ). This resulted in an enormous instantaneous intensity in the femtoliter focal volume that elicited the material’s nonlinear optical response. Two-photon excited fluorescence (TPEF) is one manifestation of this nonlinear process. The fluorescence emission is localized exclusively within the focal volume resulting in the inherent “optical sectioning” property of multiphoton microscopy.18 The thickness of each optical section was determined by the axial transfer function of the optical multiphoton imaging system, which was measured to be for our experimental configuration. The excitation light represented a pulsed femtosecond laser, which was a tunable, computer-controlled titanium-sapphire laser (MaiTai, Spectra Physics) whose wavelength was set to . The laser pulsewidth and repetition rate was and , respectively. The incident optical power was set to 20 and in stratum corneum and epidermis, respectively. A focused laser spot was raster-scanned across the sample using two galvanometer mirrors. The excited fluorescence was collected by the same objective lens. A dichroic mirror transmitted fluorescence to the detection photomultiplier tube (PMT), while reflecting the IR laser excitation light. In the detection arm, the fluorescence was split between two channels terminated by two optical detectors (PMTs) following preselected spectral filters. A narrow-bandpass interference filter (BP380, Omega Optical) centered at , with a FWHM of , was inserted in channel 1 to selectively detect ZnO PL signal. In channel 2, a broad bandpass filter (BG39, Schott glass color filter) with a long-wavelength cutoff of was employed to block the excitation laser light so that the skin autofluorescence emission was captured. An image was formed by recording detector signals versus the focal spot position in the sample. The two images from the two channels were overlaid at a postprocessing stage. To optimize the spectral filter configuration in the detection arms, a preliminary imaging experiment using two samples was conducted. Sample 1 represented Dr Lewinns’ cosmetic formulation diluted to a concentration of 0.005% and spin-coated on a glass slide to form nanoparticles and clusters. Sample 2 was a skin patch prepared, as already described in this section. The results of multiphoton imaging of these samples are presented in Fig. 2 . Panels on the left- and right-hand-side columns show images of samples 1 and 2, respectively. The top and bottom images were obtained using the broadband (BG39) and UV narrowband (BP380) filters, respectively. Suppression of autofluorescence from caprylic/capric triglycerides solvent, visible as structured layout [Fig. 2a], is evident by comparing panels in Figs. 2a and 2b. Likewise, the strong skin autofluorescence [Fig. 2c] is efficiently filtered by the UV narrowband filter [Fig. 2d]. The excised skin sample was deprived of NAD[P]H resulting in reduced autofluorescence intensity, probably dominated by FAD fluorescence.14 Note that although the broadband emission in the visible spectrum of ZnO and ZnO-nano has been reported previously,19 it was not observed in this study, probably owing to the high crystal quality of our ZnO-nano sample. Fig. 2MPM images: (a) and (b) ZnO-nano (scattered bright dots) the capric/caprilic oil film cast on a glass slide; (c) and (d) excised skin patch. Epidermal cellular architecture is clearly observable in (c). Images (a) and (c) and (b) and (d) are detected using the broadband (channel 1) and narrowband (channel 2) spectral filters, respectively. Scale bar .  3.ResultsFigure 3 shows our first in vivo images of human skin treated with the zinc oxide commercial formulation. Overlaid multiphoton images of human skin in vivo and ZnO-nano distribution, after its topical application, are colorcoded green and red, respectively. En face optical sections of the skin are displayed from top left to bottom right at depths 0, 3, 14, 22, 30, and from the skin surface designated S. The depth readout was corrected for the confocal parameter, calculated as , where denotes a difference between the axial position readout at a depth and top surface settings, and denotes the mean refractive index of tissue, which was set to a mean value of 1.4 (Ref. 20). ZnO-nano patterns are clearly observable on the skin autofluorescence background, and especially pronounced on the topmost layers of the skin. Fine morphological details of unstained skin are clearly observable, e.g., cell structure in stratum granulosum (Fig. 3, bottom left panel), with dark nuclei and a granulated pattern in the cell cytoplasm, presumably, originated from NAD[P]H accumulated in mitochondria. As Fig. 3 shows, ZnO-nano predominantly remained on the topmost layer of SC within a several-micrometer layer (image panels S to ). The nanoparticle localization in the skin folds and dermatoglyph is clearly evident from Fig. 3 . No penetration of ZnO-nano into the cells or extracellular space was observed. Fig. 3Overlaid MPM images of human skin in vivo (color-coded green) and ZnO-nano distribution (color-coded red) after its topical application. En face optical sections of the skin are displayed from top left to bottom right at depths of 0, 3, 14, 22, 30, and from the skin surface designed S and 3, 14, 22, 30, and , respectively. Note ZnO localization in stratum corneum and in skin folds. No presence of nanoparticles in the stratum granulosum layer (ellipsoidal cells with dark nuclei) is observable. Scale bar .  Figure 4 shows images for the skin subdermal absorption of ZnO-nano after occupational exposure to the sunscreen formulation for various times. The skin of the three human subjects of different ethnical origins was imaged and analyzed using time-lapse in vivo MPM imaging of skin: shortly, and after topical application of the formulation. No traces of ZnO were present in the viable epidermis (Viable Epidermis, Fig. 4), other than a well-confined island of ZnO in a skin fold (dark clearly outlined area) at after the sunscreen application in Caucasian skin, subject B. Images of SC acquired after sunscreen application show complete removal of sunscreen from skin, probably as a result of the daily shower routine exercised by each human subject in this experiment. In effect, this suggests ZnO-nano subdermal absorption after longer exposures is also unlikely. Fig. 4Overlaid in vivo MPM images of ZnO-nano (color-coded red) distribution in human skin, forearm, dorsal side (color-coded green). Optical sections of stratum corneum and viable epidermis are grouped in two blocks. Each row displays images of three human subjects: Asian female, Chinese, aged below 30; Caucasian male, aged 30 to 40; and Indian male, aged 40 to 50, are designated by A, B, and C, respectively. Each column displays time-lapse image sequence acquired: , , , following the ZnO-formulation topical application. Scale bar .  MPM also enabled the investigation of alternative pathways of nanoparticle penetration, such as the appendages, as represented by the hair follicle canal. Since the hair follicle shaft can extend at a considerable depth in skin, or greater, it can potentially represent an entry port of materials directly into the viable epidermis. Figure 5 shows an MPM cross-sectional image of the freshly excised human skin topically treated with the sunscreen formulation. As described previously, no penetration of ZnO-nano is observable. At the same time, a prominent ZnO signal is noticeable at the perimeter of the hair follicle (white arrow). The hair shaft is not visible in the image. The sunscreen is localized in the hair follicle shaft without spreading to the neighboring cells and tissue. Our systematic studies of the nanoparticles penetration via this route confirmed this observation.21 Fig. 5Overlaid MPM images of the freshly excised human skin (color-coded green) and ZnO-nano distribution (color-coded red) after its topical application. An arrow points to the hair follicle canal, where a hair follicle shaft is not visible. ZnO formulation is localized around the hair follicle. Scale bar .  To verify our MPM observations, we carried out high-resolution, high-sensitivity SEM/EDX measurements of ZnO nanoparticle penetration in the excised skin topically treated with ZnO-nano. Figure 6 shows the results of our observations. An SEM image shows a low-magnification morphological layout of the skin cross-section. In the central part of the image, a wedge-like skin fold converges inward. Several fragments of the bright-contrast debris are clearly localized in this skin fold. The EDX technique enables atomic species analysis locally. Integral x-ray spectra sampled at two sites of interest, SC/skin fold (solid circle) and epidermis (dashed circle) are shown in left-hand side panels Fig. 6. At least two prominent peaks of zinc (ZnK, ZnL, corresponding to excitation of the core electron shells in a zinc atom) and one oxygen peak were observed in the skin fold, as shown in panel EDX: stratum corneum. These are suggestive of the presence of ZnO in the skin fold, as expected considering the topical application of the sunscreen formulation on the skin. We note that ZnO-nano existed predominantly in an agglomerated phase. In contrast, no noticeable peaks were observed in the epidermis, as EDX:epidermis panel shows. This result confirms our observation made by using multiphoton microscopy: ZnO-nano remained on the skin surface. Fig. 6SEM image (right-hand side panel) and EDX spectra (left-hand side panels) of the excised human skin topically treated with ZnO-nano. The EDX spectra sampled from the stratum corneum/skin fold (solid circle) and epidermis (dashed circle) areas are displayed in top (EDX: SC) and bottom (EDX: epidermis) left-hand side panels, respectively. Note EDX spectrum in SC shows two prominent peaks of atomic zinc origin (ZnL, ZnK). C, O, Zn, P, denote corresponding chemical elements. The ending letters K and L denote the characteristic binding energies of the core electron shells. Scale bar .  4.DiscussionThe ZnO-nano nonlinear optical contrast on the cell autofluorescence background is remarkable and unexpected. This contrast could be due to several factors. First, the PL of ZnO nanoparticles is considerably enhanced compared to bulk ZnO. Guo 22 have reported that the third-order nonlinear susceptibility of ZnO-nano sized is almost 500-fold of that of bulk ZnO. As this enhancement is likely to be due to quantum confinement effects, ZnO-nano, with a size of several tens of nanometers, exhibits quantum dot properties. The systematic study of versus ZnO-nano size in the size range of has revealed a quadratic size dependence, with measured23 to be (expressed in cgs system of units) at and . Second, ZnO-nano emission typically occurs in three major spectral bands centered at (UV), (green), and (orange). The orange emission is broadband, and is due to oxygen interstitial defects, which disappear after high-temperature annealing in air.19 Although the origin of the green broadband emission is not well understood, it is commonly believed to originate from oxygen vacancy defects. These defects may be situated on the surface of a ZnO-nano, and hence amenable to surface treatment by capping with polymer.22 Further, as the surface capping resulted in considerable suppression of the broadband emission in green (accompanied by the UV emission enhancement) several other capping-free ZnO-nano synthetic routes yield similar results.19, 24 Our sample exhibited no detectable emission bands in the visible spectral range (see Fig. 1). As maintained in the literature, the narrowband UV emission at is unlikely to be due to direct bandgap transition, as the Stokes shift between the absorption and emission bands is too large. It is hypothesized and corroborated experimentally that the UV emission is due to deep donors associated with oxygen vacancies. A PL-induced electron populates this vacancy followed immediately by its recombination with an available hole (exciton recombination) accompanied by a UV photon emission. These donors are localized and their population density in the nanocrystal is high, leading to dramatic enhancement of the quantum confinement effect and enhanced UV emission. To evaluate attainable contrast of ZnO-nano on the autofluorescence background of skin, we compared the two-photon excitation fluorescence signal from ZnO-nano with that of the endogenous fluorophores typical to skin. The two-photon absorption cross-section of ZnO-nano, , which is governed by a third-order nonlinear process,25 can be found by using the third-order nonlinear susceptibility, of ZnO reported in the literature26 where stands for the Plank’s constant, is the optical angular frequency; denotes nanoparticle concentration recalculated from the molar concentration of (reported in Ref. 22); is the refractive index of ZnO at , which amounts to 2.0; is speed of light; is the dielectric permeability constant. We convert from in the cgs system of units to in the SI system of units. Substitution of these values to Eq. 1 yieldsfor an ZnO particle at , where we used a convention of for two-photon absorption cross-section. To evaluate a fluorescent signal from our sample, it is important to determine the nanoparticle action cross-section , which is defined as a product of the absorption cross-section and quantum yield . Here represents a number of fluorescence photons emitted per one absorbed photon (per two photons in TPEF). According to the literature reports,27 the ZnO quantum yield varies depending on the crystal and surface quality, with a typical value of . The two-photon action cross-section is evaluated to be for an particle typical for our experimental conditions. This value is much less compared to that of water-soluble Qdots, (Ref. 10), and exogenous (externally introduced) fluorophores, such as fluorescein, . At the same time, is favorably comparable to that of the dominant skin endogenous fluorophores, including reduced NAD[P]H, FAD, and retinol, whose does not exceed28 at .In the context of multiphoton imaging, the visibility of ZnO-nano material against the skin autofluorescence background is determined by its TPEF cross-section relative to that of endogenous fluorophores, its relative concentration, and its fluorescence emission spectral overlap with the dominant skin fluorophores. Skin autofluorescence has been investigated,29 both in vitro and in vivo. The skin autofluorescence spectrum has been reported in the literature to feature three major component bands centered at 450, 520, and on excitation in the wavelength range of . The first two spectral bands corresponded to 75 and 25% of the total spectrum intensity, respectively.15 These two peaks in the skin autofluorescence spectrum correspond to the fluorescence emission peaks of the endogenous skin fluorophores that include collagen, elastin, NAD[P]H, and FAD (Ref. 29), whereas the peak at corresponds to porphyrins. Skin autofluorescence background, excited as a result of the nonlinear optical processes, is somewhat different. It is spectrally separated into an intense SHG signal from collagen, which occurs at a precisely half the laser excitation wavelength (UV range), a narrow emission band from , and a broadband emission from (see Fig. 1) (Ref. 14). In live skin, the autofluorescence spectrum in epidermis is dominated by NAD[P]H, as this coenzyme is involved in cellular energy metabolism. Vitamin derivatives, such as flavins, also have a noticeable contribution to the autofluorescence spectrum of epidermis in vivo. In the excised epidermis, the NAD[P]H contribution is markedly reduced due to degradation of the metabolic cycles, resulting in the reduced autofluorescence level and its spectral red-shift due to keratin and to some extent flavin components. Note that the ZnO UV absorption band is advantageous to enable spectral discrimination of its emission signal from most endogenous fluorophores of skin, including NAD[P]H, riboflavin, folic acid, and retinol, all having emission bands in visible. At the same time, the emission band of pyridoxine falls28 into that of ZnO, and demands attention in certain imaging scenarios. However, for the nanoparticle transdermal penetration study, confined to the SC and viable epidermis, such collagen-related molecules as pyridoxine, pose little problem, since they are predominantly present in dermis. The SHG signal from collagen [see Fig. 1b] did not present a problem due to its predominant location in the dermis. Further, this signal wavelength is precisely half the wavelength of the excitation source so that it may fall outside the ZnO PL spectral range. The ZnO-nano UV PL spectral band may overlap with that of the other endogenous fluorophores, leading to a degraded imaging contrast. The femtosecond laser excitation wavelength of used in our experiments is suboptimal for the excitation of ZnO TPEF, as the ZnO bandgap width of requires two-photon excitation at a fundamental wavelength of . At the same time, dependence versus falls off gradually from , whereas (Ref. 23). At the same time, Iripman have noted a steep increase of versus the laser intensity.23 Therefore, our evaluation of [see Eq. 2] must be treated as only a rough estimation. Note that, unlike in case of free excitons, characterized by , in the size range , revealing the bound exciton nature of ZnO-nano. Also is sensitive to the crystal/surface quality. Our preliminary data on the nonlinear optical signal intensity versus input power suggests that three-photon nonlinear optical absorption makes a slight additional contribution to the excitation of ZnO-nano.16 Although has been recently measured, no data on the three-photon absorption cross-section of ZnO-nano has been reported to the best of our knowledge. Application of the adapted multiphoton imaging system to imaging ZnO-nano enabled us to examine the existing hypothesis on the nanoparticle penetrability through the normal intact skin. Importantly, we have been able to investigate this question in vivo and show that the ZnO-nano did not penetrate human skin either in vitro or in vivo. This work is important, as it addresses the first aspect that may have caused ZnO-nano toxicity penetration. This work suggests that ZnO-nano, of about in size, does not penetrate human skin. In contrast, the smaller molecules, such as salicylic acid , do penetrate the skin.30 This is consistent with a number of in vitro investigations of cosmetic-origin ZnO-nano penetration in skin that have been reported.31, 32 In our study, we used caprylic capric triglycerides formulation for ZnO-nano, which promotes passive diffusion of nanoparticles via a lipophilic intercellular pathway. This pathway represents the principle transdermal penetration route, and hence represents the most stringent test of the ZnO-nano penetrability, except for active skin enhancers. Electron micrographs of human skin show ZnO-nano mineral components are present on the surface of the skin and around desquaming corneocytes17 and not in deeper tissues. Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Agency has actively supported the notion that ZnO and remain on the surface of the skin and in the outer dead layer (SC) of the skin.26 The data contrasts the most recent results by Ryman-Rasmussen that Qdots of the size range of did penetrate porcine skin, long considered a reliable model of the human skin.33 Three types of the Qdot nanoparticles with positive, neutral, and negative charges on the Qdot surface were found in epidermis and dermis passed the SC, followed the skin topical application in vitro. These Qdots were shown to cause a severe immunological cellular response, ultimately resulting in cell apoptosis.34 The size range of our ZnO nanoparticles was commensurable with that reported by the authors. Based on our results21 (also, to be communicated elsewhere), we argue that porcine skin represents a poor model of human skin in the context of transdermal penetrability to nanoparticles. Receptor phase penetration of zinc through the human epidermal membrane has been observed over using the Franz cell-based technique,17 although it was likely to be negligible and in a form of hydrolyzed zinc ions rather than integral ZnO-nano. In this context, it is unlikely that ZnO-nano would be toxic if skin penetration had occurred. Cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, and photogenotoxicity studies on or other insoluble nanoparticles should be interpreted with caution, since such toxicities may be secondary to phagocytosis of mammalian cells exposed to high concentrations of insoluble particles. Studies on wear debris particles from surgical implants and other toxicity studies on insoluble particles support the traditional toxicology view that the hazard of small particles is mainly defined by the intrinsic toxicity of particles, as distinct from their particle size. There is little evidence supporting the principle that smaller particles have greater effects on the skin or other tissues or produce novel toxicities relative to micro-sized materials. Overall, the current weight of evidence suggests that nano-materials such as nano-sized vesicles or ZnO and nanoparticles currently used in cosmetic preparations or sunscreens pose no risk to human skin or human health, although other nanoparticles may have properties that warrant safety evaluation on a case-by-case basis before human use. 5.ConclusionWe investigated in vitro and in vivo skin penetrability to nanoparticles of the size range typical to that used in cosmetic products, i.e., . For the first time, the application of multiphoton microscopy has enabled imaging of both the wide bandgap nanostructures, e.g., ZnO-nano, and skin tissue/cellular architecture. ZnO appeared to have surprisingly high visibility against the skin autofluorescence background, which was attributed to its enhanced nonlinear two-photon action cross-section favorably compared to that of the skin endogenous fluorophores, e.g., NAD[P]H and FAD; and “transparency window” of skin autofluorescence at occupied by the ZnO-nano principle photoluminescence. Nanoparticles have been found to stay on the SC, or fell into skin folds or hair follicle roots, thus, confirming safety of the ZnO-nano-based cosmetic products in vivo. ReferencesG. J. Nohynek,

J. Lademann,

C. Ribaud, and

M. S. Roberts,

“Grey goo on the skin? Nanotechnology, cosmetic and sunscreen safety,”

Crit. Rev. Toxicol., 37

(3), 251

–277

(2007). 1040-8444 Google Scholar

G. P. H. Dietz and

M. Bahr,

“Delivery of bioactive molecules into the cell: the Trojan horse approach,”

Mol. Cell. Neurosci., 27

(2), 85

–131

(2004). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2004.03.005 1044-7431 Google Scholar

A. Beduneau,

P. Saulnier, and

J. P. Benoit,

“Active targeting of brain tumors using nanocarriers,”

Biomaterials, 28

(33), 4947

–4967

(2007). 0142-9612 Google Scholar

Z. P. Xu,

Q. H. Zeng,

G. Q. Lu, and

A. B. Yu,

“Inorganic nanoparticles as carriers for efficient cellular delivery,”

Chem. Eng. Sci., 61

(3), 1027

–1040

(2006). 0009-2509 Google Scholar

P. H. Youl,

P. D. Baade,

M. Janda,

C. B. Del Mar,

D. C. Whiteman, and

J. F. Aitken,

“Diagnosing skin cancer in primary care: how do mainstream general practitioners compare with primary care skin cancer clinic doctors,”

Med. J. Aust., 187

(4), 215

–220

(2007). 0025-729X Google Scholar

R. Alvarez-Roman,

A. Naik,

Y. Kalia,

R. H. Guy, and

H. Fessi,

“Skin penetration and distribution of polymeric nanoparticles,”

J. Controlled Release, 99

(1), 53

–62

(2004). 0168-3659 Google Scholar

K. F. Lin,

H. M. Cheng,

H. C. Hsu,

L. J. Lin, and

W. F. Hsieh,

“Band gap variation of size-controlled ZnO quantum dots synthesized by sol-gel method,”

Chem. Phys. Lett., 409

(4–6), 208

–211

(2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2005.05.027 0009-2614 Google Scholar

R. Dunford,

A. Salinaro,

L. Z. Cai,

N. Serpone,

S. Horikoshi,

H. Hidaka, and

J. Knowland,

“Chemical oxidation and DNA damage catalysed by inorganic sunscreen ingredients,”

FEBS Lett., 418

(1–2), 87

–90

(1997). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-5793(97)01356-2 0014-5793 Google Scholar

H. A. Jeng and

J. Swanson,

“Toxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles in mammalian cells,”

J. Environ. Sci. Health, Part A: Toxic/Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng., 41

(12), 2699

–2711

(2006). 1093-4529 Google Scholar

D. R. Larson,

W. R. Zipfel,

R. M. Williams,

S. W. Clark,

M. P. Bruchez,

F. W. Wise, and

W. W. Webb,

“Water-soluble quantum dots for multiphoton fluorescence imaging in vivo,”

Science, 300

(5624), 1434

–1436

(2003). https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1083780 0036-8075 Google Scholar

H.-Y. Lee,

Y.-R. Chang,

K. Chen,

C.-C. Chang,

D.-S. Tsai,

C.-C. Fu,

T.-S. Lim,

Y.-K. Tzeng,

C.-Y. Fang,

C.-C. Han,

H.-C. Chang, and

W. Fann,

“Mass production and dynamic imaging of fluorescent nanodiamonds,”

Nat. Nanotechnol., 3 284

–288

(2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2008.99 1748-3387 Google Scholar

Z. F. Li and

E. Ruckenstein,

“Water-soluble poly(acrylic acid) grafted luminescent silicon nanoparticles and their use as fluorescent biological staining labels,”

Nano Lett., 4

(8), 1463

–1467

(2004). https://doi.org/10.1021/nl0492436 1530-6984 Google Scholar

H. M. Cheng,

K. F. Lin,

H. C. Hsu, and

W. F. Hsieh,

“Size dependence of photoluminescence and resonant Raman scattering from ZnO quantum dots,”

Appl. Phys. Lett., 88

(26), 261909

(2006). 0003-6951 Google Scholar

J. A. Palero,

H. S. de Bruijn,

A. V. van den Heuvel,

H. Sterenborg, and

H. C. Gerritsen,

“Spectrally resolved multiphoton imaging of in vivo and excised mouse skin tissues,”

Biophys. J., 93

(3), 992

–1007

(2007). https://doi.org/10.1529/biophysj.106.099457 0006-3495 Google Scholar

R. H. Na,

I. M. Stender,

L. X. Ma, and

H. C. Wulf,

“Autofluorescence spectrum of skin: component bands and body site variations,”

Skin Res. Technol., 6

(3), 112

–117

(2000). 0909-752X Google Scholar

D. C. Dai,

S. J. Xu,

S. L. Shi,

M. H. Xie, and

C. M. Che,

“Efficient multiphoton-absorption-induced luminescence in single-crystalline ZnO at room temperature,”

Opt. Lett., 30

(24), 3377

–3379

(2005). https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.30.003377 0146-9592 Google Scholar

S. E. Cross,

B. Innes,

M. S. Roberts,

T. Tsuzuki,

T. A. Robertson, and

P. McCormick,

“Human skin penetration of sunscreen nanoparticles: in-vitro assessment of a novel micronized zinc oxide formulation,”

Skin Pharmacol. Appl. Skin Physiol., 20

(3), 148

–154

(2007). 1422-2868 Google Scholar

K. Konig,

A. Ehlers,

F. Stracke, and

I. Riemann,

“In vivo drug screening in human skin using femtosecond laser multiphoton tomography,”

Skin Pharmacol. Appl. Skin Physiol., 19

(2), 78

–88

(2006). 1422-2868 Google Scholar

H. M. Cheng,

H. C. Hsu,

S. L. Chen,

W. T. Wu,

C. C. Kao,

L. J. Lin, and

W. F. Hsieh,

“Efficient UV photoluminescence from monodispersed secondary ZnO colloidal spheres synthesized by sol-gel method,”

J. Cryst. Growth, 277

(1–4), 192

–199

(2005). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2004.12.133 0022-0248 Google Scholar

V. Tuchin, Tissue Optics: Light Scattering Methods and Instruments for Medical Diagnosis, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston

(2000). Google Scholar

A. J. X. Zhao,

J. A. Ross,

M. Sarkar,

W. Sanchez,

A. V. Zvyagin, and

M. S. Roberts,

“Nanoparticles penetration through human skin, much ado about nothing,”

22

(2007) Google Scholar

L. Guo,

S. H. Yang,

C. L. Yang,

P. Yu,

J. N. Wang,

W. K. Ge, and

G. K. L. Wong,

“Highly monodisperse polymer-capped ZnO nanoparticles: preparation and optical properties,”

Appl. Phys. Lett., 76

(20), 2901

–2903

(2000). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.126511 0003-6951 Google Scholar

L. Irimpan,

V. P. N. Nampoori,

P. Radhakrishnan,

B. Krishnan, and

A. Deepthy,

“Size-dependent enhancement of nonlinear optical properties in nanocolloids of ZnO,”

J. Appl. Phys., 103

(3), 033105

(2008). 0021-8979 Google Scholar

M. M. Demir,

R. Munoz-Espi,

I. Lieberwirth, and

G. Wagner,

“Precipitation of monodisperse ZnO nanocrystals via acid-catalyzed esterification of zinc acetate,”

J. Mater. Chem., 16

(28), 2940

–2947

(2006). https://doi.org/10.1039/b601451h 0959-9428 Google Scholar

R. L. Sutherland, Handbook of Nonlinear Optics, Marcel Dekker, New York

(1996). Google Scholar

“A review of the scientific literature on the safety of nanoparticulate titanium dioxide or zinc oxide in sunscreens,”

(2006) Google Scholar

M. Schubnell,

I. Kamber, and

P. Beaud,

“Photochemistry at high temperatures—potential of ZnO as a high temperature photocatalyst,”

Appl. Phys. A: Mater. Sci. Process., 64

(1), 109

–113

(1997). 0947-8396 Google Scholar

W. R. Zipfel,

R. M. Williams,

R. Christie,

A. Y. Nikitin,

B. T. Hyman, and

W. W. Webb,

“Live tissue intrinsic emission microscopy using multiphoton-excited native fluorescence and second harmonic generation,”

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 100

(12), 7075

–7080

(2003). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0832308100 0027-8424 Google Scholar

N. Kollias,

R. Gillies,

M. Moran,

I. E. Kochevar, and

R. R. Anderson,

“Endogenous skin fluorescence includes bands that may serve as quantitative markers of aging and photoaging,”

J. Invest. Dermatol., 111

(5), 776

–780

(1998). https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00377.x 0022-202X Google Scholar

K. Harada,

T. Murakami,

E. Kawasaki,

Y. Higashi,

S. Yamamoto, and

N. Yata,

“Invitro permeability to salicylic-acid of human, rodent, and shed snake skin,”

J. Pharm. Pharmacol., 45

(5), 414

–418

(1993). 0373-1022 Google Scholar

Z. S. Kertesz and

A. Z. Kiss,

“Quality of skin as a barrier to ultra-fine particles,”

(2003–2004) Google Scholar

C. G. J. Hayden,

S. E. Cross,

C. Anderson,

“Sunscreen penetration of human skin and related keratinocyte toxicity after topical application,”

Skin Pharmacol. Appl. Skin Physiol., 18

(4), 170

–174

(2005). 1422-2868 Google Scholar

J. P. Ryman-Rasmussen,

J. E. Riviere, and

N. A. Monteiro-Riviere,

“Penetration of intact skin by quantum dots with diverse physicochemical properties,”

Toxicol. Sci., 91

(1), 159

–165

(2006). 1096-6080 Google Scholar

J. P. Ryman-Rasmussen,

J. E. Riviere, and

N. A. Monteiro-Riviere,

“Surface coatings determine cytotoxicity and irritation potential of quantum dot nanoparticles in epidermal keratinocytes,”

J. Invest. Dermatol., 127

(1), 143

–153

(2007). 0022-202X Google Scholar

|